“We have to face the shameful facts.” So said the Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte on 17 February as he endorsed a new state-funded study into the “extreme violence” committed by the Netherlands during the 1945-49 Indonesian war of independence. Rutte apologised to the people of Indonesia for the “colonial war” waged by the Dutch after the territory it had ruled for more than 300 years declared independence. An estimated 100,000 Indonesians were killed in the conflict and 5,300 soldiers died on the Dutch side.

Dutch and Indonesian researchers on the €6.4m investigation, which began in 2017, found that the Dutch armed forces in Indonesia used violence systematically, burning villages and detaining, torturing and executing people. Those atrocities were condoned by politicians, society and the media in the Netherlands, the authors said, due in part to a “deep-rooted colonial mentality”. The full results of their study will be published this year in a series of 12 books by Amsterdam University Press and available for free online.

The findings rewrite the decades-old official Dutch narrative that the army behaved correctly during the conflict in spite of “excesses”. And they come on the heels of another national institution’s reckoning with this turbulent, yet relatively little-known history: Revolusi! Indonesia Independent, a timely exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Running until 5 June, it is the third show staged under the leadership of director Taco Dibbits to address the Netherlands’s history of colonialism, after Good Hope: South Africa and the Netherlands from 1600 in 2017 and Slavery in 2021.

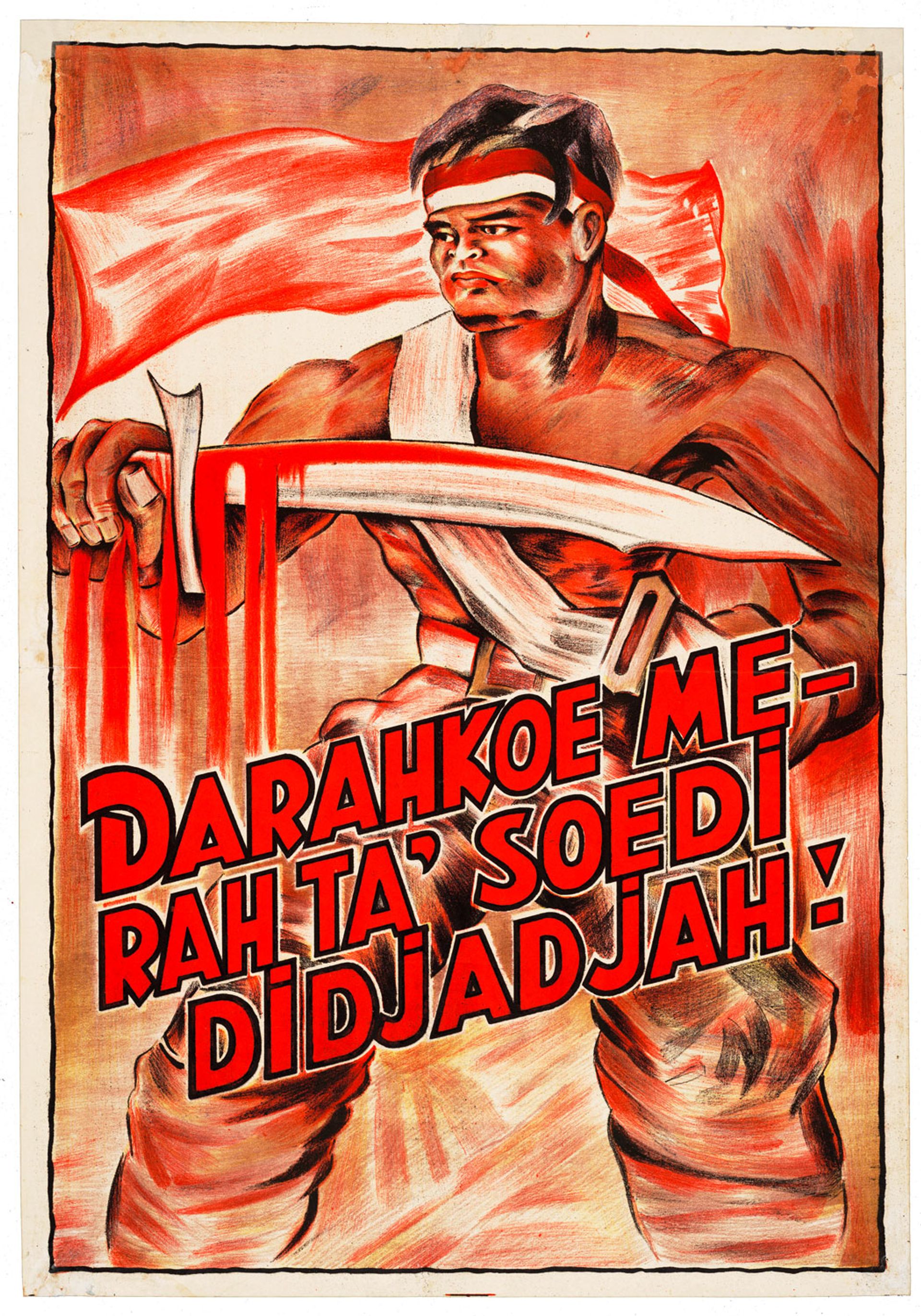

Indonesian propaganda poster with the slogan "Darahkoe merahta’soedi

didjadjah!" (my blood is red, unwilling to be conquered!) (around 1945-49), part of the National Archives of the Netherlands in The Hague

Revolusi! narrates the struggle for Indonesian independence through more than 200 objects associated with 23 “eyewitnesses”, presenting “stories told for the first time and images never seen before”, Dibbits said at a press preview. The approach mirrors that of the Slavery exhibition, which was structured around ten individuals with a range of perspectives on slavery.

“We would like to show people that the Indonesian revolution is not only about the violence but also about the spirit—that people were encouraged and desired to create a new nation, to make a better life [for future generations],” says the Indonesian historian Bonnie Triyana, one of the show’s four curators. Despite challenges posed by the pandemic, which limited international travel and access to archives, the curatorial team have collaborated across continents since 2018: Harm Stevens and Marion Anker of the Rijksmuseum’s history department together with Triyana and the Indonesian museum director and auction house founder Amir Sidharta.

Trubus Soedarsono's painting of his mother, Iboekoe (1946) Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

War or revolution?

There have been “clashing debates” in Indonesia since the 1970s, Triyana says, over whether the 1945-49 period should be defined as a revolution or as a war of independence. He argues that “war” places a too-narrow focus on military combat, whereas “revolution”—the exhibition’s chosen title—“involves more people from many backgrounds”, not least the Indonesian artists who joined the independence movement in significant numbers.

Indeed, the Revolusi! exhibition threads together—quite literally, in the form of a red painted line running along the walls of the galleries—a chorus of figures, including revolutionary fighters but also journalists, diplomats, mothers and artists. This kind of “polyphony” is vital to understanding a revolution that was itself “chaotic, confusing, fluid and self-contradictory”, writes the historian and University of Amsterdam professor Remco Raben, one of the specialists consulted by the exhibition curators, in a catalogue essay.

A dress made from British Royal Air Force silk maps of Southeast Asia by Jeanne van Leur-de Loos, a Dutch repatriate from Indonesia Photo: Rijksmuseum/Albertine Dijkema

Experts helped to source objects for display that had long been kept in private family collections, Triyana says, for example a bullet-riddled army shirt worn by a Balinese pro-Republican fighter, Tjokorda Rai Pudak, who was shot dead by a local militia working with a Dutch patrol. Another gallery spotlights a dress made from British Royal Air Force silk maps of Southeast Asia by Jeanne van Leur-de Loos, a Dutch repatriate from Indonesia who had been held in a Japanese internment camp during the Second World War. Other personal artefacts were confiscated from their owners by the Dutch intelligence service and reside today in archives in the Netherlands.

Modern visual culture

Many of the exhibits testify to what Stevens of the Rijksmuseum calls a “modern visual culture” that rapidly developed in the nascent Republic of Indonesia, including propaganda posters, photography, film and painting. Bookending the show are photographs capturing key political moments: Soemarto Frans Mendur’s tiny vintage print in the first room of the nationalist leader Sukarno declaring independence on 17 August 1945 and a series by the French photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson, published in Life magazine, of Sukarno’s presidential inauguration after the Netherlands transferred sovereignty to Indonesia in December 1949.

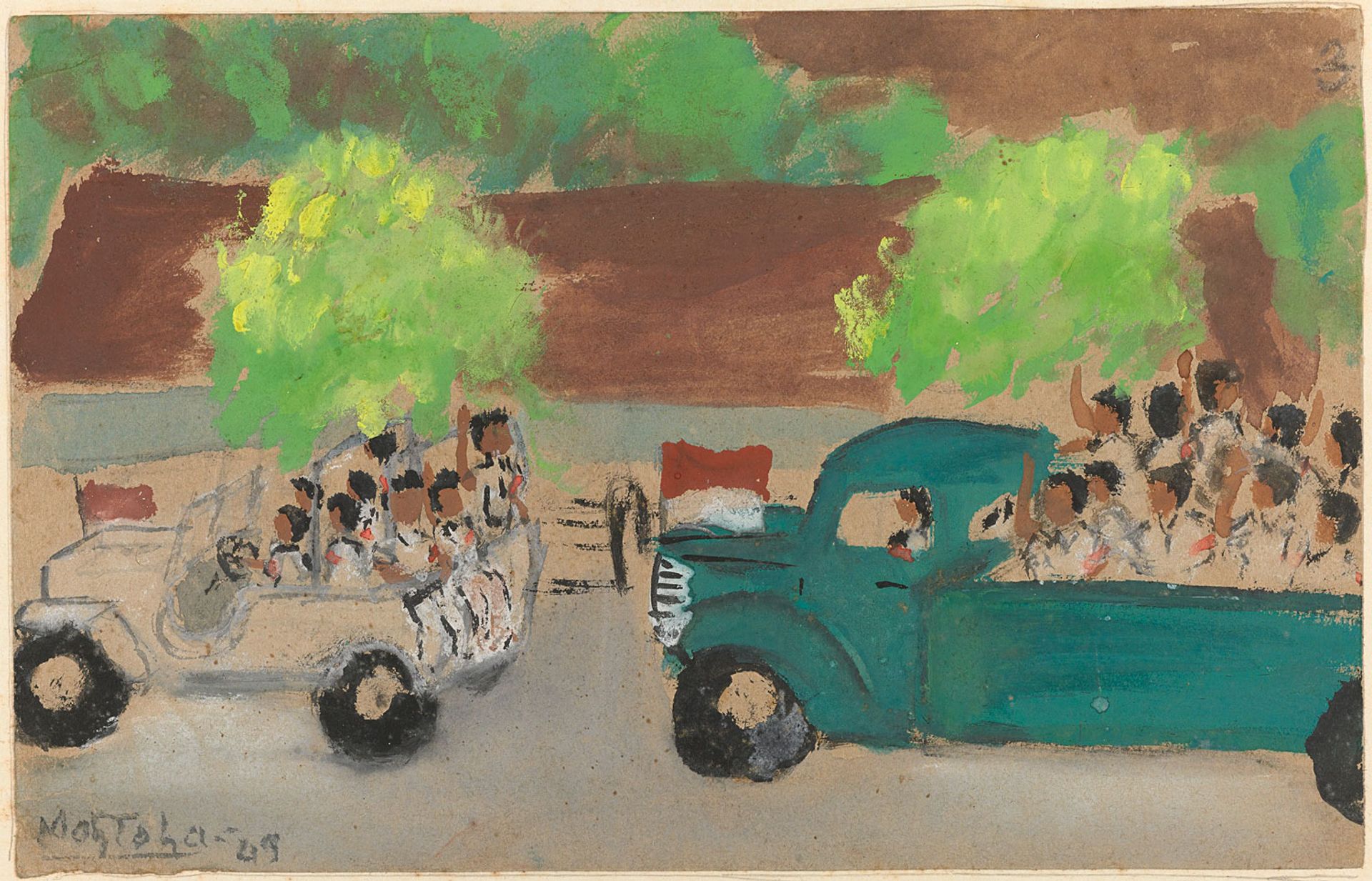

Republican Troops Returning to Yogyakarta (1949) by Mohammad Toha, an 11-year-old boy who documented the Dutch occupation of his city in secret watercolour sketches

More striking, however, is a set of unofficial documentary images: miniature watercolours painted by Mohammad Toha, aged 11 at the time of the 1948-49 Dutch bombing and occupation of Yogyakarta, the Republican capital. Toha was one of five child street vendors trained by the painter Dullah to make sketches of their city in secret. One boy went missing and another died in a children’s prison, while Toha survived to see his paintings acquired by the Rijksmuseum 50 years later.

And alongside examples of political propaganda produced by artists in the service of the revolution are more subtle works of art. A dedicated paintings gallery includes a sympathetic portrait on sackcloth of a captured Indonesian spy. Painted by the artist Affandi, who was close to Sukarno’s elite, it emphasises the common humanity of an enemy collaborator. Viewers need to look closely at Iboekoe (my mother) (1946) by one of Affandi’s pupils, Trubus Soedarsono, to spot the patriotic symbol pinned to her lapel, the red-and-white Indonesian flag.

Luka dan bisa kubawa berlari (wounds and venom I carry as I’m running) (2022), a new commission for the exhibition by the Indonesian artist Timoteus Anggawan Kusno Photo: Rijksmuseum/Albertine Dijkema

Yet ultimately, the art here serves to illuminate a complex, contested history whose legacies live on today. This is clearest in a contemporary commission from the Indonesian artist Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, who was invited to respond to the Rijksmuseum’s collection from the period. His gallery-filling installation, Luka dan bisa kubawa berlari (wounds and venom I carry as I’m running) (2022), combines empty frames that once held state portraits of the governors of the Dutch East Indies with flags of anti-colonial resistance.

For Kusno, the ghosts of the paintings are “the symbol of the continuity of the colonial regime that lasted for centuries” and its afterlife today. “We are still dealing with the haunting image of colonialism,” he says.

• Revolusi! Indonesia Independent, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, until 5 June