Enough already! The daily onslaught of NFT headlines had begun to feel like another plague, and at first, I chose to ignore it. When crypto-creators registered their tokens, I did not see art. Instead, I saw lava lamps. I saw currency trading. A way for people stuck at home by the pandemic to vent through a handy digital outlet. I’ve never had any trouble accepting video, film, photography, performance or books as mediums for art. What was I missing here?

I turned to Leo Villareal, the artist who turned the bridges over the River Thames into LED light sculptures. Even when his often mesmerising installations were realised in rapidly changing, never-repeating, sequences of light, they had a physical structure—a relationship to the human body—and I was down with that. On 24 January Villareal dropped his first NFTs as 1,024 unique tokens collectively titled Cosmic Reef on the year-old Art Blocks platform. The “edition” sold out within an hour. The average price of each iteration was 0.4 Ether (ETH), or around $1,500. Multiplied by 1,024, the sale earned Villareal $1.7m, of which 90% went straight to his digital wallet.

NFT enlighteners (left to right): James Parker Healy, Yvonne Force Villareal, Jeff Davis and Leo Villareal Photo: Linda Yablonsky

“It took me a while to wrap my head around it,” Villareal admitted. He invited me to his studio in Brooklyn. I went with his art consultant wife, Yvonne Force Villareal, another naïve but one less sceptical than I. By chance, Jeff Davis, a digital artist and chief creative officer of Art Blocks, arrived at the same time. Villareal’s friend James Parker Healey, an electronic musician and collector of NFT art, also joined us. It would take all four of them to make this new art form comprehensible to me, and I’m still not sure. But they did open my mind to the concept.

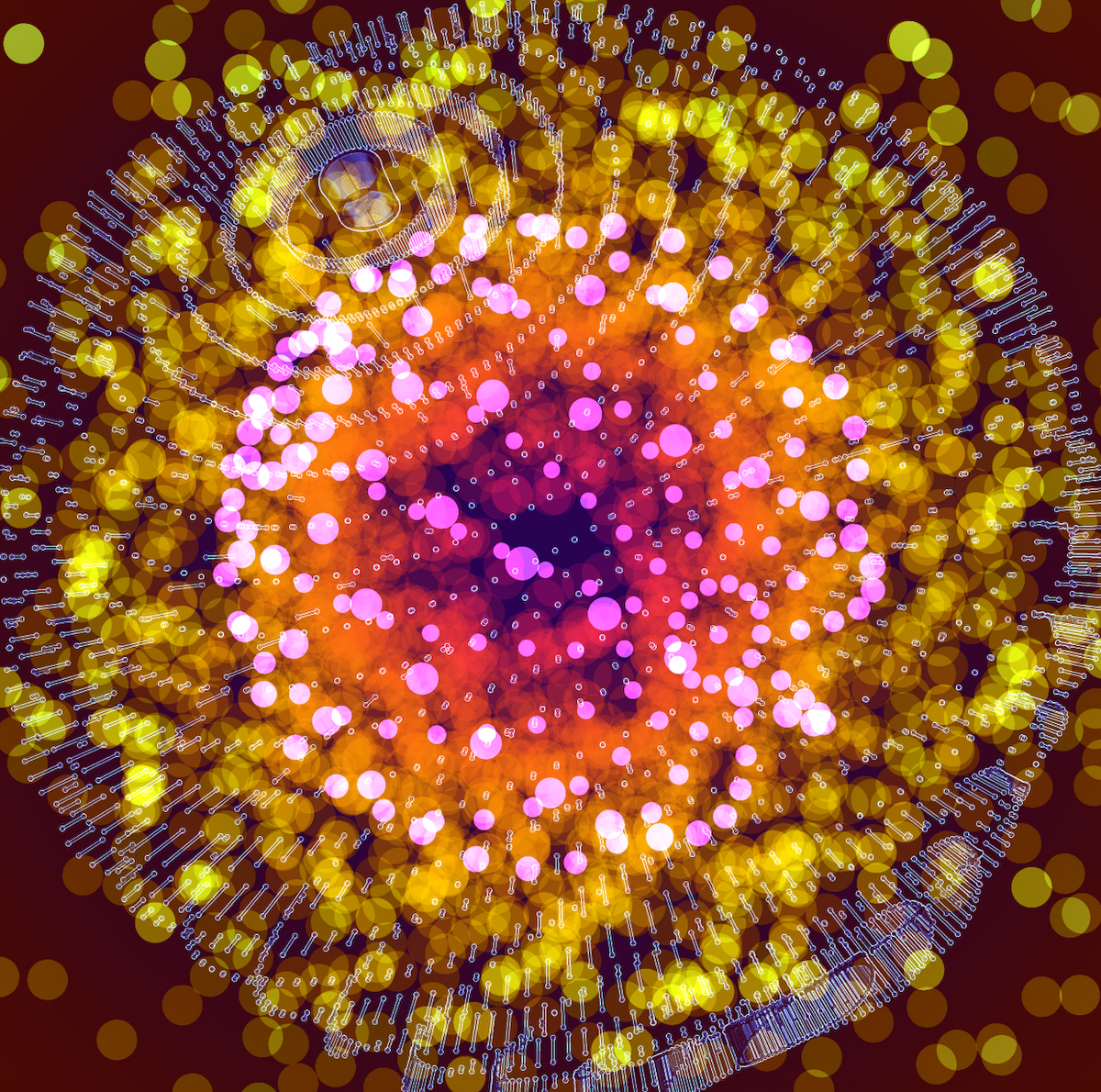

“Cosmic Reef is a generative artwork,” Villareal told me. “It’s system-based, a framework for the art input. There are randomised outlets inside the framework, so you don’t always know what’s going to happen when it creates a large series that explores the system you’ve developed.” I wasn’t just playing dumb…

“It’s like having a baby,” Force Villareal explained, more helpfully. “You don’t know the colour of its eyes or hair. Each NFT happens as it’s being made from parameters that Leo set.” Villareal starts with simple geometry, like a sphere, and adds unique features. They are not digital postcards. Thus, the algorithm for Cosmic Reef created 1,024 outputs assembled randomly from his script. Some of their attributes are considered rarities that drive up the resale price. In other words, buyers don’t know which iteration of an NFT drop they’re getting till they open it. “If you don’t like what you see, you can sell it and try to buy what you want on the secondary market,” he added.

Can Villareal’s looping animations captivate someone who isn’t zoned out on drugs?

All of this was as dizzying as Villareal’s animations, which play in endless loops. Can they captivate someone who isn’t zoned out on drugs? Or does ownership alone compel interest? And how do viewers actually engage with such technology? According to Davis, “It’s still early days. That’s still being sorted out.” For Villareal, “with all of the light sculptures I make, I can control how they look and display. With NFTs you’re creating an electronic piece of art that has the display and the code built into it, but it can be viewed in many different ways—on a phone, on a computer screen, on a TV screen. And I’m okay with that.”

He’s also pleased that Art Blocks has a philanthropic arm for artists on its “curated” platform for next-level art. Villareal donated 25% of the proceeds from the sale of his NFTs to charities. “I’ve never been in that position before,” he said. According to Davis, in the 18 months since the platform’s inception, its artists have given a whopping $49m to nonprofits.

Villareal’s LED works capture the structures of natural phenomena like wind, planets, oceans, flowers, circulatory systems—all that moves and grows—in choreographies of pixels, lights and code. Cosmic Reef is no different, except that it’s closer to virtual reality. In theory, a metaverse-adhering collector could avoid shouldering the expense of building a new wing on their house to display physical artworks by constructing virtual rooms for digital holdings. All anyone would need to enjoy it is a VR headset.

Who is buying NFTs? “Most are young, first-time collectors,” Healey told me. “These are people who have screens in every room, and they leave them on 24/7.” Yet, according to recent reports, successful collectors are spending their crypto fortunes on physical art in galleries. Late last year, at Sotheby’s, the tech entrepreneur Justin Sun paid $78.4m for a Giacometti, an artist he’d never heard of before. Museums are getting into the act as well. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art now owns a piece of Tom Sachs’s Rocket Factory NFT.

“It’s so crazy,” said Force Villareal. Her husband replied, “I can hardly wait to do it again.”