The framed wedding photo that Dor Guez has of his grandmother, Samira, was torn and bent when he first found it in a suitcase of family snapshots. A white gash shrouded her forehead where a bridal veil would normally be, the image’s damage eerily matching its subject. Before enlarging and printing the image, Guez used his custom scanogram technique to scan the tattered photograph three times into a layered composite that gave the ripped area texture. “She’s looking straight directly into the camera, and in a way, history is gazing back at you,” Guez says of this haunting manipulated readymade, which hangs in his Jaffa living room and at the entrance to his most comprehensive solo institutional exhibition to date, opening at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogotá (MAMBO) on 10 March. “It represents the fracture and diaspora of 1948, and the point at which borders were erected and communities were divided and destroyed.”

Samira’s wedding took place in the city of Lod (also known as Lydda) in 1949, a year after Israeli military forces took control of her Jaffa hometown. It was the first Palestinian wedding after al-Nakba (Arabic for catastrophe)—the mass exodus of Palestinians from land claimed by Israel during the 1948 war. The history gazing at us through her eyes is that of 1948 and its aftermath, a story the Jerusalem-born Guez is uniquely poised to tell as an artist of Palestinian Christian, and Jewish Tunisian descent. Catastrophe is the title and subject of his exhibition, displaying works created between 2008 and this year, including video installations, photographs, scanograms and original source materials, with some works being shown for the first time.

Dor Guez, from the Catastrophe series (2021) Courtesy of the artist, Dvir Gallery, Goodman Gallery, and Carlier Gebauer Gallery

“The more you deal with a specific narrative, like my own family's personal catastrophe, the more it tells a broader story,” says Guez of the universal themes he hopes resonate with audiences in Bogotá and later in Mexico City, when Catastrophe travels to Laboratorio Arte Alameda. Eugenio Viola, chief curator at MAMBO (and curator of the Italian pavilion at the 2022 Venice Biennale), adds that “even if he is working on a specific situation and social, geographical, political context, it can give a broader overview on intolerence”.

The works being exhibited for the first time—a three-channel video installation titled Colony (2022), photographic series called Catastrophe (2021) and video work titled Hippos (2022)—are new and old, since Guez uses archives and historied places as starting points. The artist mines the potential of timeworn images and expands their meaning, causing viewers to see history anew.

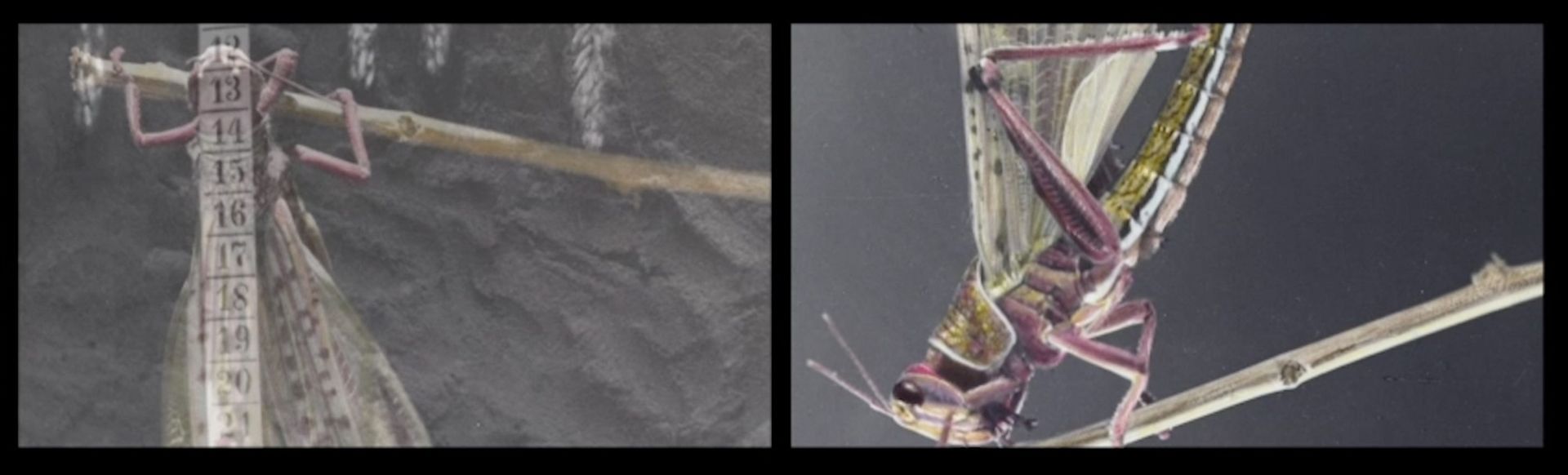

Dor Guez, Colony, 2022 Courtesy of the artist, Dvir Gallery, Goodman Gallery, and Car-lier Gebauer Gallery

In Colony, which Guez has worked on for the past five years, scientific close-ups of locusts and black-and-white footage of insect swarms in British Mandatory Palestine evoke biblical plagues. Images migrate between the film’s three screens to a high-pitched soundtrack of grasshoppers, as ominous narration in Arabic describes invasive colonies with ambiguous language that could apply to either locusts or people. “The ability of organisms to convert from harmless individuals to a synchronized, ruthless unit is unsettling,” says the narrator, in an all-knowing nature documentary tone. Some images almost align between screens, but partitions set them off-kilter.

Fragmentation repeats as a formal feature in many the works on view in Catastrophe. Hippos, a video filmed at an ancient Hellenistic site in the Golan Heights, is bisected into two channels—one historic, one contemporary. The Catastrophe series of landscape photographs shows a pine forest planted by the Jewish National Fund after 1948, near Lod where Guez’s family lived, obscuring remnants of Palestinian homes damaged during the Nakba. The photos of these fallen trees and broken archways are splintered into triptychs. Another photographic series, 40 Days (2013), documents the deliberate desecration of family gravestones in Lod with images that are themselves poetically eroded after being stashed in a kitchen drawer (police were unable to use them to find those who perpetrated the hate crime and returned the photos to Guez’s family, who put them in a drawer for years).

Dor Guez, 40 Days, 2013 Courtesy of the artist, Dvir Gallery, Goodman Gallery, and Car-lier Gebauer Gallery

One of the source materials Guez is exhibiting is fragmented, too. Since he uses archival documents and materials heavily, the artist is displaying some original objects alongside his artworks. A stereoscopic image of a topographical map of Palestine from 1900, by definition divided into two nearly identical views that must be viewed simultaneously to create the illusion of depth, is exhibited near the Catastrophe landscape photos. “Both images look the same, but they have differences in perspective,” Guez explains. “These are intersecting perspectives, but in order to achieve a three-dimensional picture you need them both.”

Recognition of multiple narratives and perspectives, Guez believes, is a crucial step towards seeing a complete picture. In the works on view in Catastrophe, he tells the Nakba story of his family and inscribes it into the historical record.

“My work doesn't aim to prove who is right and who’s wrong. Dichotomous thinking does not interest me,” says Guez. “The idea is also to expose narratives which to a certain extent oppose the concept of nationalism.”

- Dor Guez: Catastrophe, 10 March-28 August, at Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogotá