No artist does motherhood like Louise Bourgeois. The extreme see-saws of agony and ecstasy, the bodily abjection, the blood, sweat, tears—and the breastmilk. All the maternal ambivalence that any mother, including your correspondent, knows all too well is brilliantly exposed in The Woven Child, the Hayward Gallery’s exemplary exhibition of works using textiles and fabric made by Bourgeois from the mid 1990s until her death in 2010.

Of course with Bourgeois there is also a lot else going on, but what struck the strongest chord with me was the fantastically inventive way in which, from the rigorously abstract to the viscerally figurative, she grappled with what it means both to be and to have a mother. This, of course, includes everyone, whether they have kids or not. It also stirred up memories of my first meeting with Louise Bourgeois in New York more than 30 years ago.

Installation view of Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child at Hayward Gallery, London, 2022. © The Easton Foundation/DACS, London and VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Mark Blower/© The Hayward Gallery

I didn’t even know I was pregnant with my first son when I went to visit Louise Bourgeois in April 1991. I put my queasiness down to apprehension at meeting an artist whom I massively admired and who was also notorious for giving interviewers a hard time. I hadn’t embarked on being a parent and Bourgeois had not yet made the vast majority of the works now on show at the Hayward, but the experience of this encounter, and my bit part in the family drama that was preoccupying her at the time, had a profound effect that still gives me the shivers today.

The Chelsea brownstone looked pretty much like all the others in the street. Yet the window grille was a subtle giveaway, with the bars bulging outwards and drooping downwards in two pendulous folds, as if they had been melted from within—designed by Louise, I later learned.

I waited on the same stoop where Bourgeois had been photographed in the early 70s wearing a body-covering sheath of multiple latex breasts, until a gentle young man with the face of an El Greco saint opened the door and let me in. This was also my first encounter with Jerry Gorovoy, then Louise Bourgeois’s full time studio assistant and now president of the Easton Foundation, dedicated to preserving the Bourgeois legacy and based in the same brownstone where she lived and worked for more than half a century.

Louise Bourgeois in front of her New York City home in 1975 wearing

the latex sculpture AVENZA (1968-1969) which became part of

CONFRONTATION (1978, Coll: Guggenheim Museum, NYC).

Photo: Mark Setteducati, © The Easton Foundation

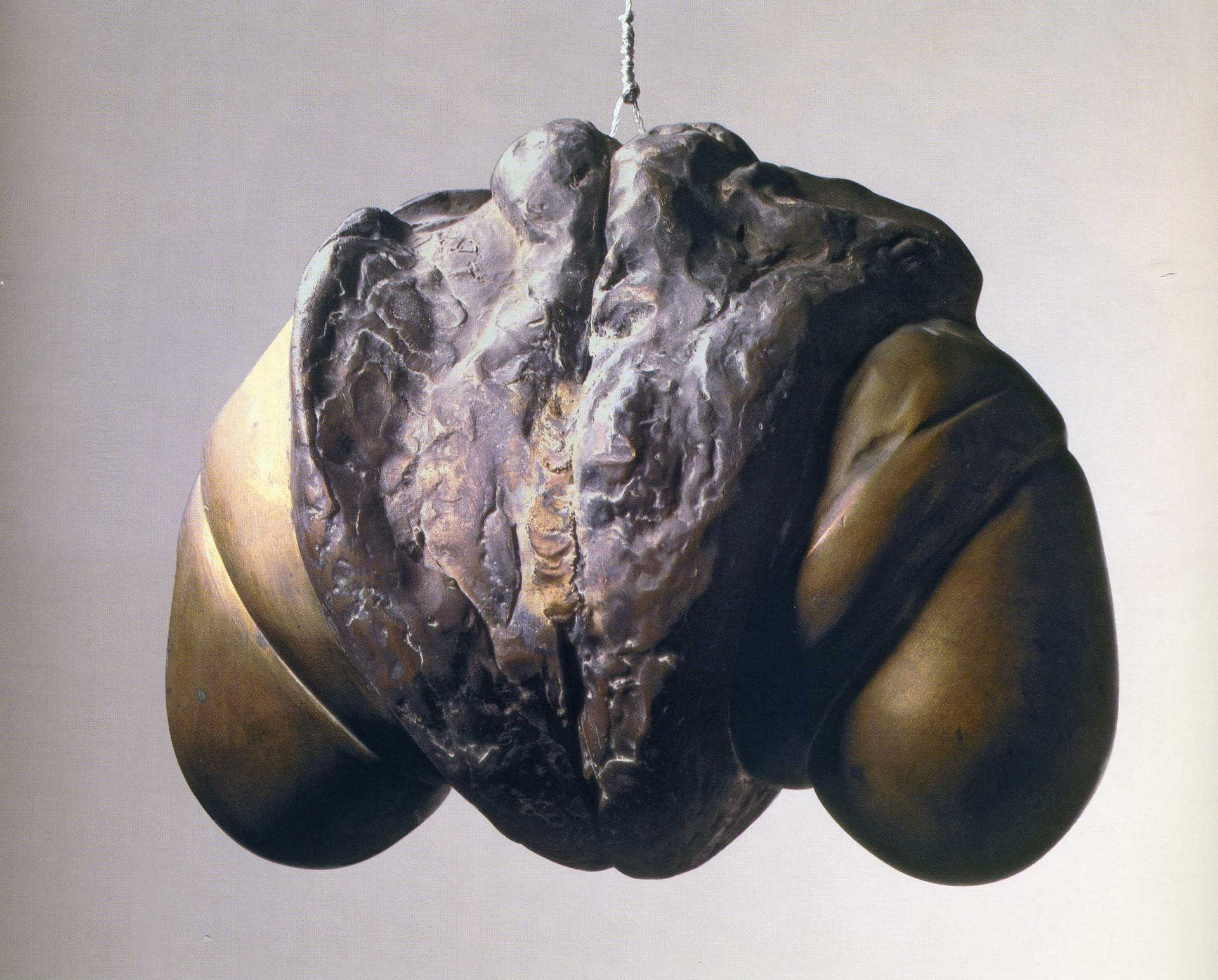

As Jerry and I negotiated the gloomy maze of rooms with their innumerable partitions, entrances, exits and bolt holes it struck me that I was in effect entering a giant Louise Bourgeois work. The artist was waiting in a shadowy booklined room, a tiny figure in a pink nylon overall perched on a throne-like highchair of polished chrome. Behind her hung an enormous exhibition poster emblazoned with a giant version of Janus Fleuri, her deeply disturbing 1968 sculpture which resembles a kind of obscene hermaphrodite croissant, with a penis shape at either end and a grainy vaginal split down the centre. It seemed to hover above her head like an obscene crown.

"Janus Fleuri means ‘Janus Blossoming’, said Bourgeois in a surprisingly strong French accent for someone who had been living in New York since 1938, "it shows the kind of polarity we represent”. And there were certainly polarities aplenty in this pint-sized force of nature whose bright beady gaze and dark hair scraped back in a girlish pony tail belied the fact that she was then nearly 80-years-old.

Louise Bourgeois's Janus Fleuri (1968). Courtesy of MoMA

“Everything is based on fear, fear to be betrayed, fear to be trapped, fear to be dependent,” she added, clutching my arm so hard that the next day I found bruises. Walking through the crepuscular spaces of her labyrinthine home, it felt increasingly like being trapped within an unfolding series of the Cell installations that Bourgeois was starting to make around this time, where it is never clear whether they are offering protection or incarceration, or an ominous mixture of both.

Especially disorientating and disconcerting was the basement cellar, a hot, dark underground chamber straight out of Silence of the Lambs which she was particularly keen to show me. I wasn’t overly reassured to learn that the house’s previous occupant had used this sinister space to take pornographic photographs, and while she insisted that the pale bulbous cobblestones covering the floor were common to all the houses in the neighbourhood there was no mistaking their uncanny resemblance to the fleshily suggestive forms that readily crop up in so many of Bourgeois’s drawings, prints and sculpture.

To me and to many others before and since, Bourgeois has described her art as a form of exorcism. Yet although she had lived in the Chelsea house with her husband, the art historian Robert Goldwater with whom she had three sons, until his death in 1973, the ghosts she conjured up during our meeting came from much earlier. “My childhood has never lost its magic, never lost its mystery or its drama,” she asserted, adding that, “nostalgia is not productive if you go to memories, but if they come to you they are the seeds of sculpture”.

Louise Bourgeois with her parents, Joséphine and Louis,

in 1915. Photo: © The Easton Foundation

And that afternoon, the memories were coming back thick and fast. Near the chrome throne in her library was a cast bronze model of an imposing family house with gaps for windows. It was just one of the many images emerging out of a fraught childhood which, according to Bourgeois, had been especially blighted and complicated by her father’s 10 year affair with Sadie Gordon Richmond, the English governess who came to live with the family in 1922, when Louise was 10. More than 60 years later, Sadie and the affair still seemed to be conjuring up intense and ambivalent emotions. It was this episode that she returned to again and again during the afternoon I spent with her.

“I was betrayed not only by my father but by her too, dammit! It was a double betrayal—it is the anger that makes me work!” she stressed, grabbing my arm again, to underline her point. But then she was also almost immediately at pains to insist that her fury was now calmed by compassion. “Sadie was not evil” she observed quietly, almost as if to reassure herself. “She was miserable. She was not an all-powerful Venus, she was a nanny taking care of brats.”

Of course Bourgeois is far too complex an artist to produce work that simply illustrated an episode from her past. But there was no doubting the strength of her conflicted emotions towards the dapper adulterous moustachioed father and the blonde, round faced young woman who gazed out from the old photographs that she showed me. At the end of our interview, when I mentioned that I lived in South London, she sent me, another blonde young English woman, to seek out and photograph Sadie Richmond’s family home in the South East London neighbourhood of Blackheath. She didn’t need to look up the address, she still knew it by heart.

A week later, standing in front of an innocuous red brick Victorian villa in Glenluce Road, SE3, I noticed that unlike all its neighbours whose garden paths were paved with tiles or concreted over, the path leading up to the front door of this particular residence was made up of the same swollen, rounded cobblestones that I’d just seen covering the basement floor of Bourgeois's house. Less of an exorcism, maybe, and more of a haunting?