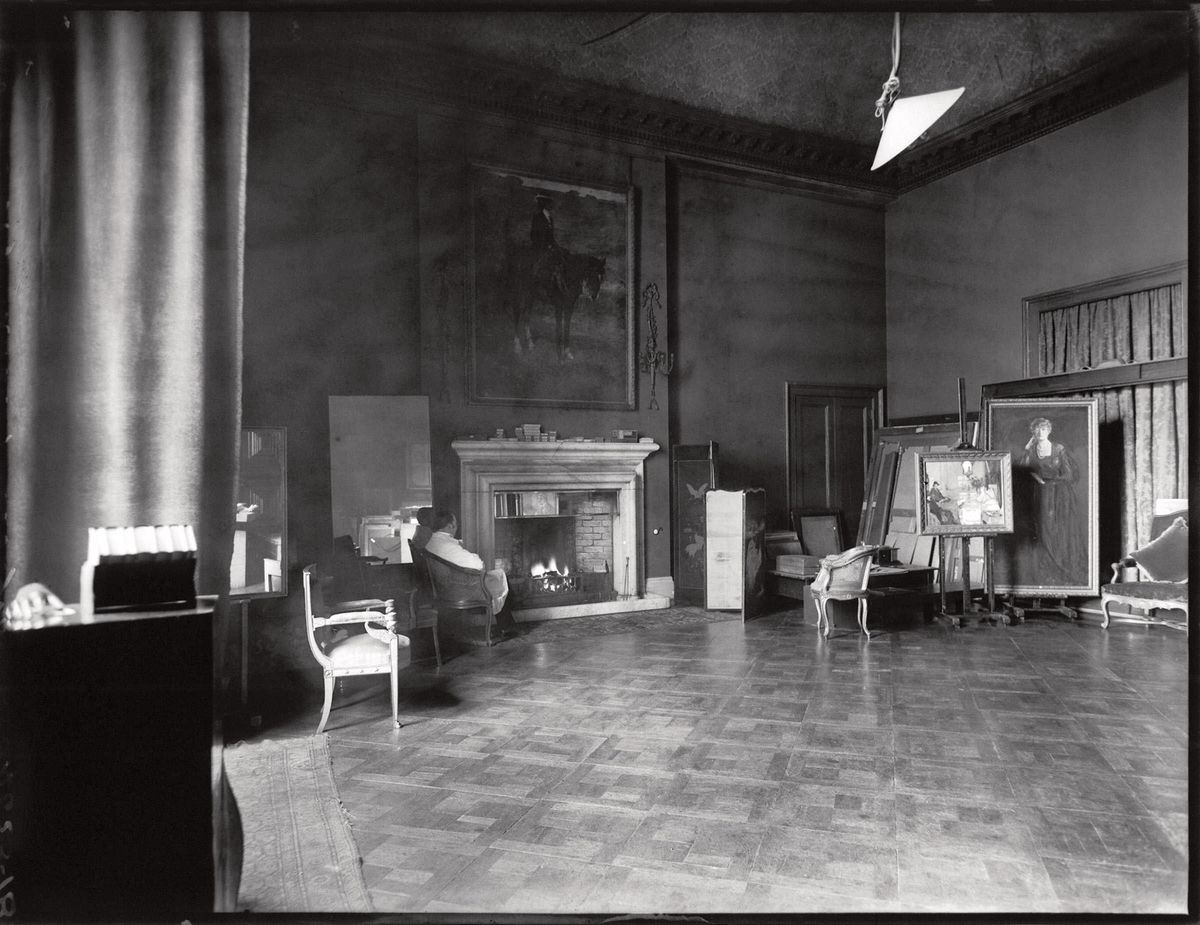

From March the public will be invited into a vast white room in South Kensington, lit by floor-to-ceiling windows, once one of the grandest artist’s studios in London. They will be following in the footsteps of its former occupant, the Irish artist John Lavery, and his high-society patrons, from royalty to the politicians who helped shape the 20th-century history of Ireland.

The studio has been restored as a new exhibition space in the Cromwell Place gallery hub, which links all five houses of the eponymous Victorian terrace across their former back gardens by a glazed bridge and new gallery. Launched in 2020, the membership organisation allows dealers, collectors and publishers to rent exhibition, office or meeting spaces by the day, week or month. Shows are open to the public free of charge. The first in the Lavery Studio, mounted by the Royal Society of Sculptors, brings together finalists for the Gilbert Bayes Award.

Born in Belfast in 1856, Lavery became a prominent society portrait painter in the early 1900s. He leased both the purpose-built studio at number five and the much larger number four, where he lived and entertained lavishly with his second wife, the dazzling American-born Hazel Martyn, herself a minor artist who gave lessons to Winston Churchill. (Across the road, number seven had been occupied by John Everett Millais a few decades earlier.)

Lavery’s visitors included King George V and Queen Mary, who inspected work in progress and complained that their blue sashes were not quite right. The artist meekly mixed up a new batch of paint, and even acceded to the royal request to apply it themselves: their wonky brush strokes can still be seen in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Both Laverys were deeply interested in Irish politics during a tense period when the guerrilla war that followed the 1916 Easter Rising led to an exhausted truce in 1921, and Ireland sent a delegation to London to negotiate for Irish independence. The team was painted by Lavery but also invited to informal suppers with the British negotiators, where many of the trickiest details could be discussed in private. The British prime minister David Lloyd George claimed to be too busy to sit, and the notoriously impatient Irish military leader and politician Michael Collins is said to have posed as briefly as possible with his overcoat on and a gun in his pocket.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed on 6 December 1921 and narrowly ratified by the Irish parliament in January 1922, gave Ireland only dominion status and not full independence. Collins famously remarked that he had signed his own death warrant, and he died in May in the Irish civil war that split the republican movement, the aftershocks of which continue to this day.

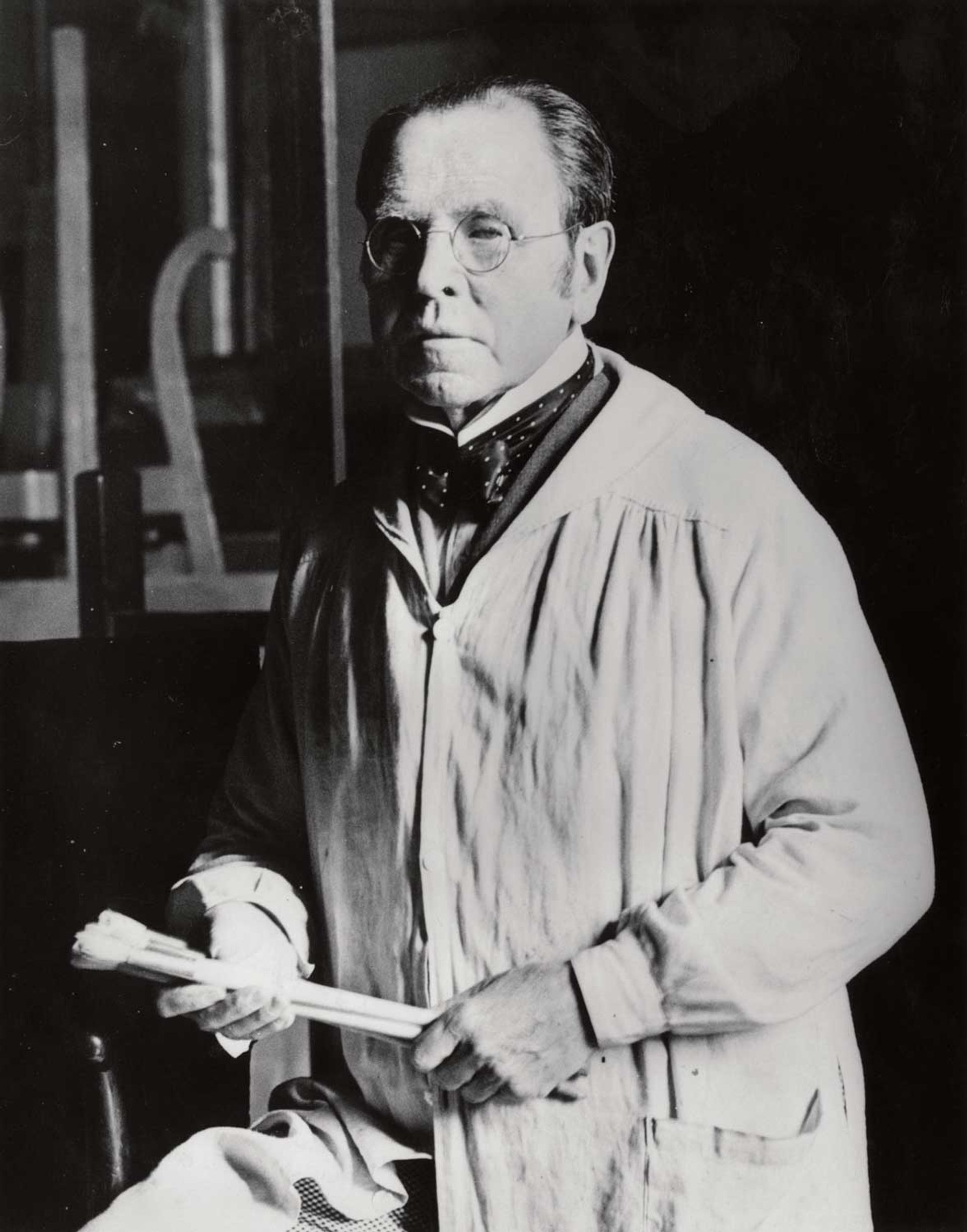

John Lavery, around 1920

Fox Photos/Getty Images

Lavery’s Treaty portraits, presented in 1935 to Dublin’s Hugh Lane Gallery to mark Hazel’s death, are currently on display with artefacts from the National Museum of Ireland, in Studio & State (until 23 December), an exhibition at the museum’s Collins Barracks building marking the Treaty’s centenary. The show’s co-curator Edith Andrees has described the Cromwell Place studio as “a place not just of art production but also of conversation, entertainment and mediation”.

Lavery later painted Hazel as Ireland personified in a romantic image commissioned for the first banknotes issued by the Irish Free State. Even when replaced by new designs in the 1970s, her image survived as a watermark until the introduction of euro banknotes in 2002.