It was Minnette de Silva, Sri Lanka’s earliest licensed female architect, who first expressed sympathy for the West’s architects. They had, she wrote in MARG—a revered architecture and art publication founded in Bombay in 1946—quite evidently missed the boat when it came to inciting a modernist revolution. “For us it is much easier,” she explained in 1953. “We have our crafts with us, still valid in our modern society. We must bring them back into an architecture which must be designed to suit our contemporary living.”

Writing at a time when South Asia was decolonising, de Silva conceived architecture as an agent for change and advanced a vision that brought regional specificity to what was largely seen as a universal modernism. That ethos, shared across the subcontinent, is explored in an ambitious new exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

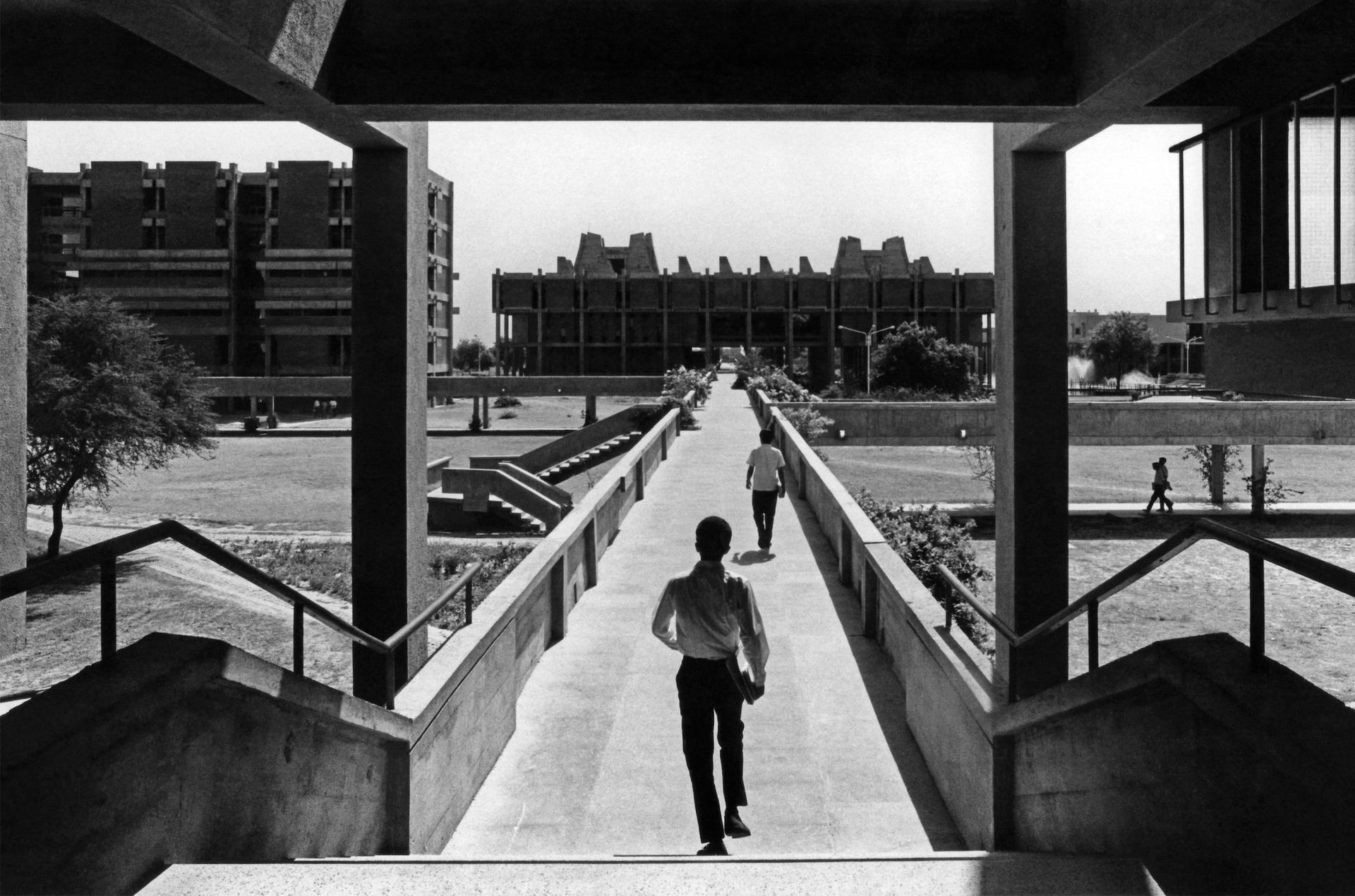

Walkways linking major buildings at the Indian Institute of Technology in Kanpur, India by Kanvinde & Rai, 1959–66. Architect: Achyut Kanvinde. Engineer: Shaukat Rai. Kanvinde Archives

Concentrated on the second half of the 20th century and foregrounding South Asia’s first generation of post-colonial architects, including Muzharul Islam, Anwar Said and Yasmeen Lari, the show brings together an array of archival ephemera, architectural models and films that are complemented by photographer Randhir Singh’s new portfolio commission. En masse, the materials impress the role architecture played in articulating and actualising what it meant to be politically sovereign after centuries of foreign imperial rule. “We’re dealing with societies that were very much engaged in reimagining themselves as progressive and forward looking,” says co-curator Martino Stierli, “modern architecture was a key tool and instrument, but in fact, actually an agent to push that progressive transformation forward.”

In a region that had finally broken away from its British colonial rulers, the redefinition of the built environment still relied to an extent on Western training. The exhibition’s co-curator, Anoma Pieris, explains that the “profession was still very young, numerically small, intimately connected and seemingly energised by an unsentimental desire to bring about change, but the tools they had were borrowed and had to be remade and rethought”. The practice of Balkrishna V. Doshi, the first Indian to be awarded the Prizker Prize (in 2018), speaks to this negotiation.

Exterior view of Chittagong University, Chittagong, East Pakistan (Bangladesh), 1965–71, by Vastukalabid (est. 1964), designed by Muzharul Islam. Photo by Randhir Singh

Following his training and work with Le Corbusier, Doshi forged his own practice underpinned by his conceptual pluralism. Doshi explored, in the words of associate curator Sean Anderson, “artistic and conceptual ideas rooted on the Indian subcontinent but not beholden to it”. In the architecture school Doshi designed for Ahmedabad’s Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology, for instance, space was configured to encourage collaborative learning—an ambition facilitated by expansive studios without doors that both accommodated the climate and Doshi’s philosophical objection to boundaries.

The way Doshi and his colleagues across the subcontinent wrangled modernism and appropriated it into a style of and for South Asia is at the exhibition’s core. This makes for a show that gives close consideration to the ways in which architectural design was influenced by such factors as the availability of materials and the abundance of labour and specific skills.

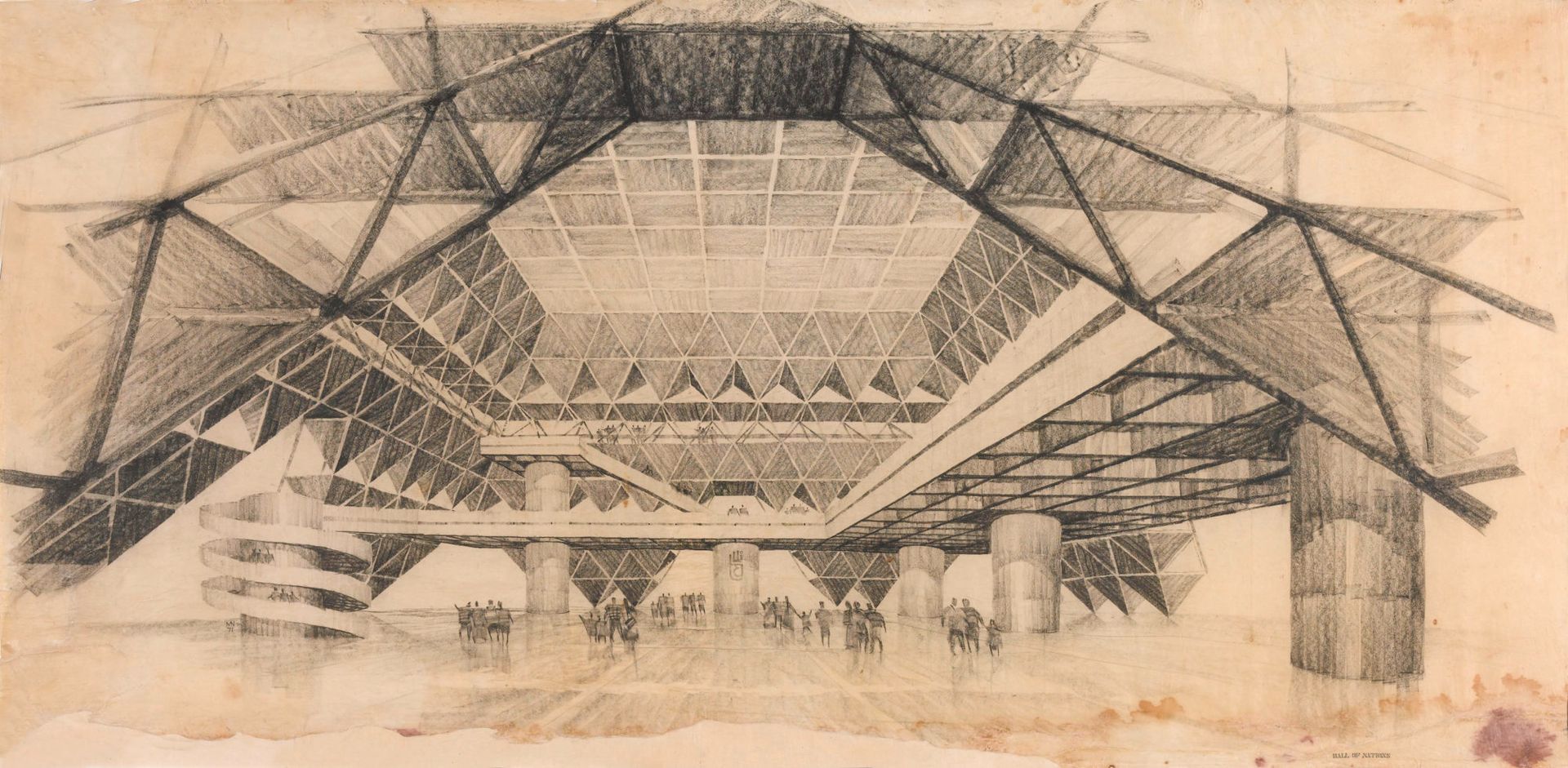

Hall of Nations, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, India, 1970–72 (demolished 2017), by Raj Rewal Associates. Architect: Raj Rewal. Engineer: Mahendra Raj. Perspective drawing, around 1970. Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou

In Delhi’s Hall of Nations and Hall of Industries, designed by Raj Rewal with engineer Mahendra Raj, the project’s economic and material challenges were taken to present design opportunities. Concrete fabrication was innovated where steel proved too costly. And with the aid of a large team, an extraordinary latticework pyramidal complex was realised in under two years. Raised to commemorate India’s 25th year of independence and accommodate a special international trade fair and conventions, the building was feted and its image promoted globally.

Now, the inclusion of Rewal and Raj’s hall comes with unanticipated poignancy. During the curatorial research phase, the building was demolished by India’s current government. Stierli says the question of preservation was among the exhibition’s central concerns. Recent events in Delhi mean the exhibition’s ambition to spread awareness of South Asia’s architectural legacy is now accompanied by a warning: buildings are aesthetic and political projects that also possess—especially when they have outlived the context which gave rise to them—the potential to be conveniently repurposed to suit the changing political tides.

- The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947–1985, until 2 July, Museum of Modern Art