After Russia annexed large swathes of eastern Ukraine and Crimea in 2014, Western countries were quick to denounce the move by imposing economic sanctions to deter further aggression. In the country’s already beleaguered culture sector, boycotts became the de facto tool for Western curators and institutions concerned with rising tensions in Ukraine.

Nearly eight years on, as the two countries teeter on the brink of war, the US and UK announced they will impose new sanctions against Russia today after Moscow recognised Luhansk and Donetsk—two self-proclaimed regions in eastern Ukraine—as independent and ordered troops there overnight.

“Many of us have been feeling tremendously isolated for quite some time already,” says Ekaterina Iragui, a Moscow-based gallerist, who adds that the situation has been getting bleaker by the day. “It’s all very aggravating, especially for the Ukrainian people,” but, she says, “it’s very short-sighted to associate the entire Russian art scene with what the government is doing.”

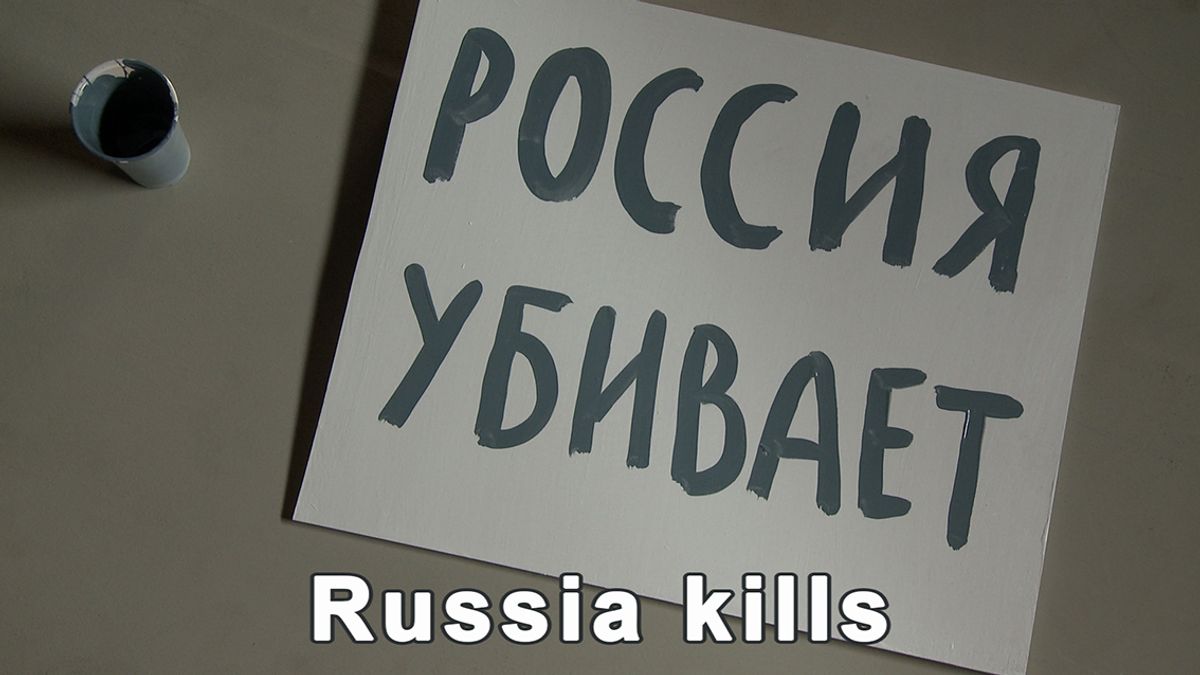

Dmitry Vilensky, a member of the Russian art collective Chto Delat, says that since 2014, the space for political activism in Russia has become more limited, “It’s now almost impossible to protest against what is going on”. He adds: “Most people in the Russian contemporary art scene do not support the reactionary turn in Russian cultural politics and certainly do not support any military [action] and colonialism in Ukraine, but because of strict control of the public sphere, it is difficult to articulate your disagreement publicly, apart from posts on social media.”

He says that many Russians already feel a sense of exclusion and disillusionment, adding that the Eastern European experience is marginalised by major international biennials and events such as this year’s Documenta in Kassel (18 June-25 September). “There is already an unwritten boycott, but not just of Russian artists—the whole Eastern European presence seems woefully under-represented on the international stage.”

Absence on the international scene

With conflict in the region now all but certain, some say that the ethos of socially engaged art has done little to advance dialogue between warring states. According to the Moscow-based art critic and Artforum contributor Sergey Guskov, “the art world has lost any claim to a common universal language.” He adds, “But I’m not only talking about English—walls are being erected everywhere.”

In Russia, many point to a lack of public financing for the arts, but this has not stopped some foreign galleries from stepping up and getting more involved in the country. “There is little to no state support for the arts in Russia,” says Olga Temnikova, the Estonia-based gallerist who is also on the board of Cosmoscow, Russia’s biggest art fair. “With the art scene in Russia already on life support, culture should be used to build bridges, especially when and where diplomacy has failed.

Anton Svyatsky, a managing partner at Fragment gallery agrees. As the only gallery with one location in Moscow and one in New York, he says that there are numerous challenges that come with focusing on Russian art in dialogue with the West. “For starters, the banking system makes it very difficult to transact between Russia and the US.”

Svyatsky notes that “there hasn’t been a single Russian art gallery to show at [the Swiss edition of] Art Basel in nearly ten years,” with Moscow not even listed as a city on Art Basel’s gallery page. Regina Gallery from Moscow took part in Art Basel in 2011 and 2012.

“Most major institutions and media are not giving visibility to artists from the former Soviet bloc, and current geopolitics make it very difficult for cultural practitioners from these countries to engage with Western institutions,” Svyatsky says. Nevertheless, he insists that “art has a function of bringing people together and overcoming differences—it is only the physical and informational barriers being erected that are becoming increasingly harder to surmount.”

Art as a healer: a satirical poster for the Moscow-based gallery Spas Setun, which was founded in 2021 Image: Courtesy of Spas Setun

The Russian government has been increasingly cracking down on dissenting artists and independent voices. In 2015 a law known as the “undesirable organisations law” was signed by President Putin barring foreign funds for non-profit art initiatives and foreign NGOs. It gives the government the power to target and disband foreign entities operating within Russia, which in the past have included the Open Society Foundations, as well as the Moscow offices of Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International.

But there are many in the country who continue to exercise freedom and independence of expression. These include the independent website and curatorial collective Tzvetnik, art groups and exhibition spaces including Plague in Krasnodar, workrooms such as Daipyat in Voronezh and artist-run spaces such as IP Vinogradov in Moscow. Funding for these usually comes from independent organisations or individuals from within Russia. Dialogue with Ukrainian artists is also happening. In December 2021, the Kiev-based artist Vova Vorotnyev exhibited at a Moscow artist-run space called Spas Setun.

According to Alexander Burenkov, an independent curator and the artistic director of the AyarKut Foundation, a non-profit art institution in Yakutia, the coldest inhabited region in the world, there needs to be more communication internationally. “We are feeling a huge sense of cultural isolation,” Burenkov says, adding that “while nobody wants war with Ukraine, the situation within the Russian art scene became complicated not because of the sanctions but due to the self-censorship and paranoid consciousness that has emerged in many formerly forward-thinking and free-spirited art institutions. At the moment, we want the international art community to know that many within Russia stand with Ukraine.”