A new Modern and contemporary art institution housed in a vast former electrical substation, which opens in Prague this week, has joined the ranks of the Czech Republic’s few privately run museums. Spanning 5,700 sq. m in the heart of the capital, the Kunsthalle Praha building was purchased eight years ago by the non-profit Pudil Family Foundation established by the collecting couple Petr and Pavlína Pudil.

The foundation has funded the €35m refurbishment of the 1930s substation building by the Czech architects Schindler Seko. Petr Pudil, who is the co-founder of BPD partners, a firm with interests in property development and agrarian chemicals, said at a press briefing (18 February) that “Prague needs contemporary architecture that responds to the need of the [city’s] citizens”, adding that the former president, Václav Havel bolstered the Czech Republic, “a small country which is at the spiritual crossroads of Europe”.

Interior view of Kunsthalle Praha. Photo: Vojtech Veskrna

At the briefing, Kunsthalle representatives revealed the scale of the new museum, outlining that 2,300 construction workers were employed on the project. Asked about the museum’s impact on the environment, Ivana Goossen, the institution’s director, says that there “are limited things we can do with a [listed] heritage building…having two layers of windows helps reduce [heat] loss and we have a sophisticated method of measuring the temperature. My main goal for 2022 is to establish our carbon footprint through the necessary data.”

The Czech government has not contributed financially towards the Kunsthalle Praha. Operational costs will be supported by grants from the Pudil Family Foundation, although the Kunsthalle will increasingly seek out other partners in future, say the Pudils and Goossen in a joint statement.

Kunsthalle Praha’s programme will encompass six to eight exhibitions a year developed in co-operation with Czech and international artists, curators and institutions. Programming will also be covered through earned revenue from ticket and membership sales, venue hire for events and the shop, as well as corporate partnerships. There is an entrance fee of 260 koruna (around €11) for visitors aged over 26.

“The [business] model may be quite novel in Prague, but is quite common internationally, especially in western Europe and the US,” the Pudils say. The former Czechoslovakia was under Communist rule from 1948 until 1990; some privately funded art venues such as Telegraph in the eastern city of Olomouc have since become more commonplace in the Czech Republic.

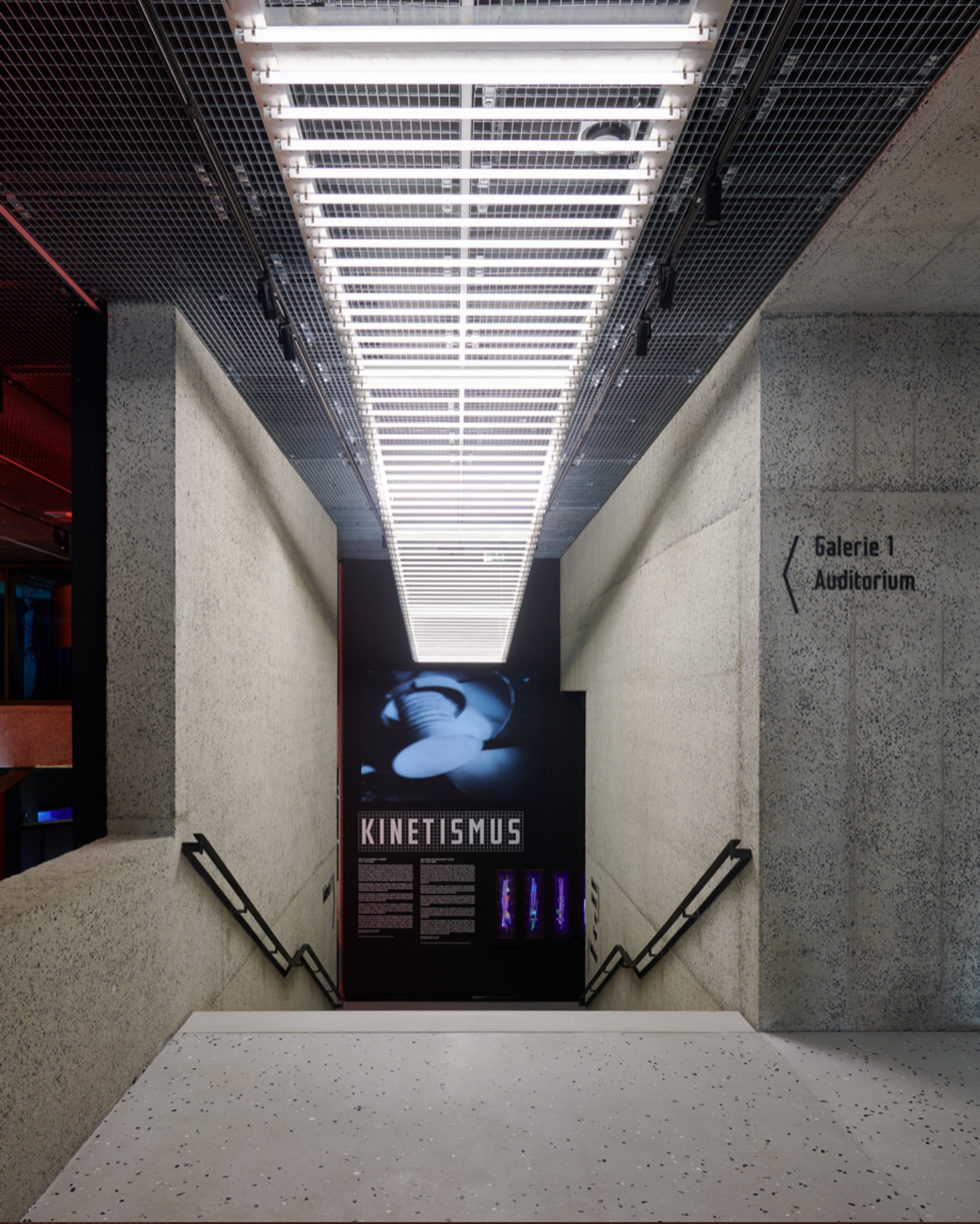

Installation view of Kinetismus: 100 Years of Electricity in Art at Kunsthalle Praha.

Unusually for a Kunsthalle—the German word for a temporary exhibition space—the institution will draw on a collection. Around 500 works from the museum’s holdings have been restored in time for the reopening owned by the Kunsthalle Praha and a further 1,500 works available for display on long-term loan, the growing collection offers “a platform to research and present Czech and Central European art in its wider international context”, the Pudils say. Lenders include other private collections such as the Eva and Petr Zeman Collection and the Robert Runtak Collection, and unusually commercial galleries: Vintage Galéria, and acb Galéria.

Installation view of Kinetismus: 100 Years of Electricity in Art at Kunsthalle Praha.

The inaugural show, Kinetismus: 100 Years of Electricity in Art (until 20 June) examines how motorised movement and artificial light have transformed artistic practice from the early 20th century to today. The show includes 93 works; Tate has loaned Angela Bulloch’s Aluminium 4 (2012) and Naum Gabo’s Kinetic Construction (Standing Wave) (1919–20, replica 1985) while Gyula Košice’s Architecture de l’eau mobile dans une demi-sphère (1963) is among works loaned by the Centre Pompidou.

Marcel Duchamp, Mary Ellen Bute and Olafur Eliasson are among the other artists featured in the Kinetismus survey, a homage to the building’s original function and to the Czech kinetic art pioneer Zdenek Pešánek who in 1930 designed but never realised a series of sculptures for the facade.

The Kinetismus exhibition includes replicas of the kinetic sculptures which vanished after being shown at the International Exhibition of arts and technology in Paris in 1937. “The only traces of this project visible on Zenger electrical substation are the four plinths nicely aligned on its facade which have remained absurdly empty since the very first day,” says a statement on the Kunsthalle Praha website. The next exhibition will be dedicated to the German artist Gregor Hildebrandt.