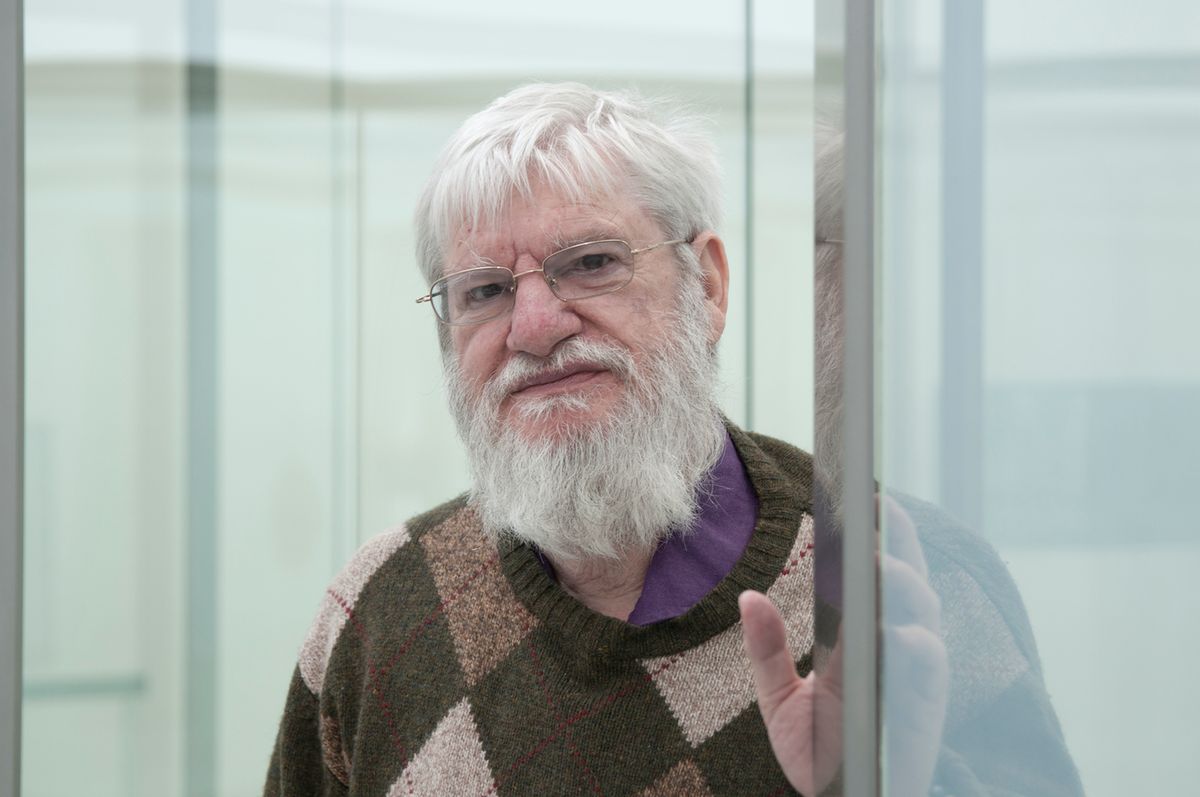

Dan Graham, an artist whose work both pioneered and transcended a number of genres including conceptual art, Minimalism, video art, architectural intervention and more, has died, aged 79. His death was announced in a joint statement from the four galleries that represented his work, which confirmed that he died this weekend in New York, where he had lived for decades.

Graham was born in Urbana, Illinois, in 1942 and raised in Winfield, New Jersey. His mother was an educational psychologist whose work with children, which often took place in playgrounds, planted a seed of curiosity in the artist into the nature of how we respond to our spatial environments. “In some ways it was oppressive, because I don’t like playgrounds,” he said in a 2015 interview, “on the other hand, I made it into a pleasure situation. [. . .] I’m taking all of the constrictive things in corporate architecture and playgrounds and making them into something playful and fun.” As he said in a 2017 conversation with Interview Magazine, a “troubled childhood” coupled with mental health issues and an abusive father led to his leaving home around age 13 to stay with a friend in Manhattan’s East Village for a time. A mediocre student, Graham never pursued a university degree. Instead, ever the voracious reader, he aspired to be a writer and though his most storied successes came as an artist, writing and storytelling remained prominent aspects of his work.

Dan Graham, Octogon for Munster, 1987, installation view at Munster Sculpture Park ©️ Dan Graham, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

In 1964 he took a job as director and curator at John Daniels Gallery on the Upper East Side, a short-lived space which is now remembered as the first gallery to give Sol Lewitt a solo show. “I had no job, and I had two friends who wanted to social climb because they were reading Esquire magazine, and a gallery looked like a cool place to social climb. They put in some money and my parents put in some money as a tax loss. I knew nothing about art,” he told Interview. “The first show I did was a Christmas show where anybody who came in could exhibit.”

Though subsequent shows included artists such as Robert Morris, Robert Smithson, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd and of course LeWitt, the gallery shuttered after less than a year without having made a single sale. “I thought of myself as a writer, and every artist who I showed, every artist who I showed in the gallery wanted to be a writer,” Graham said in his oral history with the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

Dan Graham, Stage Set for Music no 2 for Glenn, 2018 ©️ Dan Graham, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Soon after his stint as a gallerist, Graham made what might be thought of as his first artwork: photographs of suburban homes seen along the train ride from New York City to his family home in New Jersey. The mid-20th century rise and expansion of the American suburbs had created communities whose identical, orderly layouts paralleled the grid-like aesthetic of the Minimalist artists of the same era. “When I was going back to New Jersey, I discovered along the railroad tracks, situations that reminded me of Judd,” Graham told MoMA. This led to his 1966-67 work Homes for America, now in MoMA’s collection, a set of images of suburban homes intermixed with text all laid out together in an orderly manner.

Graham’s work would go on to splinter out in innumerable, often-uncategorisable directions—he began the oral history by saying, “I actually think of myself as more of a writer than an artist, and I don’t think of myself as an architect, but my work is always a hybrid”—such as with his 1983-84 film Rock My Religion, also in the MoMA collection, a montage of footage alongside text and audio elements that together parallel the history of rock music with that of alternative religions.

Dan Graham, Slightly Curvaceous, 2012 © Dan Graham, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles

His pavilion works—freestanding structures made from metal, glass, and two-way mirrors—would become his most iconic. “Graham intended his pavilions to function as punctuation marks, pausing or altering the experience of physical space, providing momentary diversion for romance or play, or else as places to delve into other activities, like reading or viewing videos,” his galleries—Lisson Gallery, Marian Goodman Gallery, 303 Gallery and Regen Projects—wrote in a statement. Using the material language of architecture to create objects of joy and wonder, these works were the ongoing, culminating response to his childhood anxieties and interests into how our environments affect our realities.

When asked in 2015 for advice for young artists, Graham replied, “Don’t make art as a career, because that means you’re just doing the same boring things that you reacted against in the beginning.” He added, “Work should be emotional in some ways, it shouldn’t be just what’s in fashion or trending. After my gallery closed, I worked knocking down walls for Roy Lichtenstein—I think people misunderstand Lichtenstein; the early work with the crying woman was his wife, who was schizophrenic. I think his work was actually emotional. So even though you fight against it, and minimal artists and conceptual artists seem to fight against emotional issues, I think you shouldn’t be afraid of them.”