The retrospective Ulysses Jenkins: Without Your Interpretation at the Hammer Museum recognises the artist’s groundbreaking role in the video art movement when the medium emerged in the 1970s. His works are marked by a pointed critique of mainstream media, specifically dealing with the representation of Black people and members of other marginalised communities.

Jenkins studied under artists including Charles White and Chris Burden, and spearheaded several art collectives, including Studio Z, alongside David Hammons, Senga Nengudi and Maren Hassinger. This overdue exhibition recognising his contributions premiered at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia last year and has been organised by the curators Erin Christovale and Meg Onli.

What propelled you to become an artist?

My first interests were drawing and painting. I saw my father doodling and thought it was fascinating. I used to draw these characters and landscapes for my siblings and make cutouts, not realising at the time that I was making installations. From that point forward, I was painting and drawing all the time. When I was getting through my undergraduate education at the Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, I became interested in Charles White and started doing ink drawings and etchings and fashioning my work behind that stylisation.

You returned to Los Angeles in 1970 and enrolled at the Otis Art Institute in 1977. What happened in between?

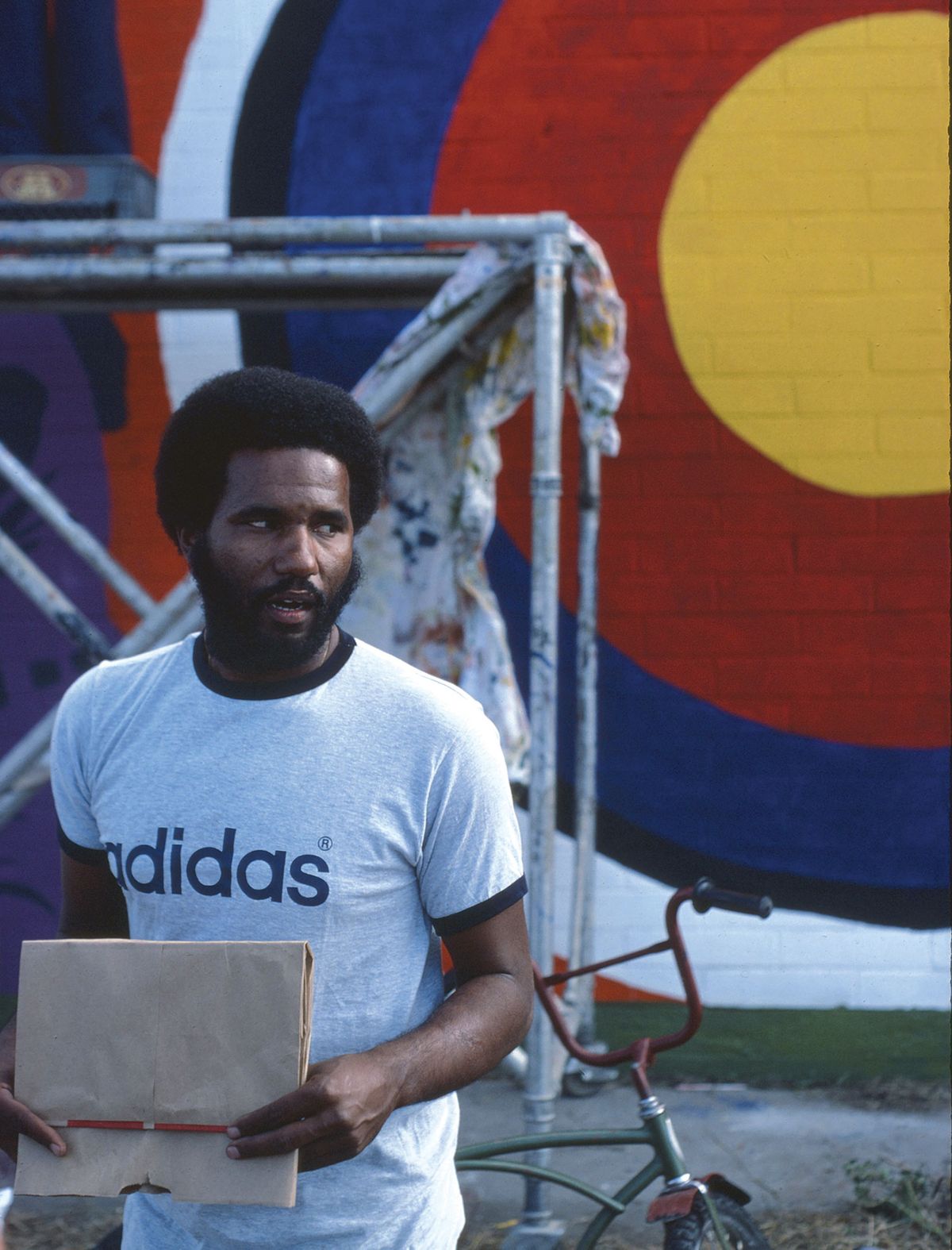

When I came back home, the idea of having an art career was circumspect, primarily because there weren’t many galleries interested in exhibiting Black artists. I briefly worked in the Los Angeles Probation Department as a counsellor and began making murals as I was leaving probation work in 1972. The first one was on Venice Beach, called The Rat Trap. It showed Los Angeles on top of a mouse trap as a metaphor for the trappings of finance and materialism. There were skulls to indicate that these things were killing us, and also marijuana fields to express that you could maybe understand this concept if you got high.

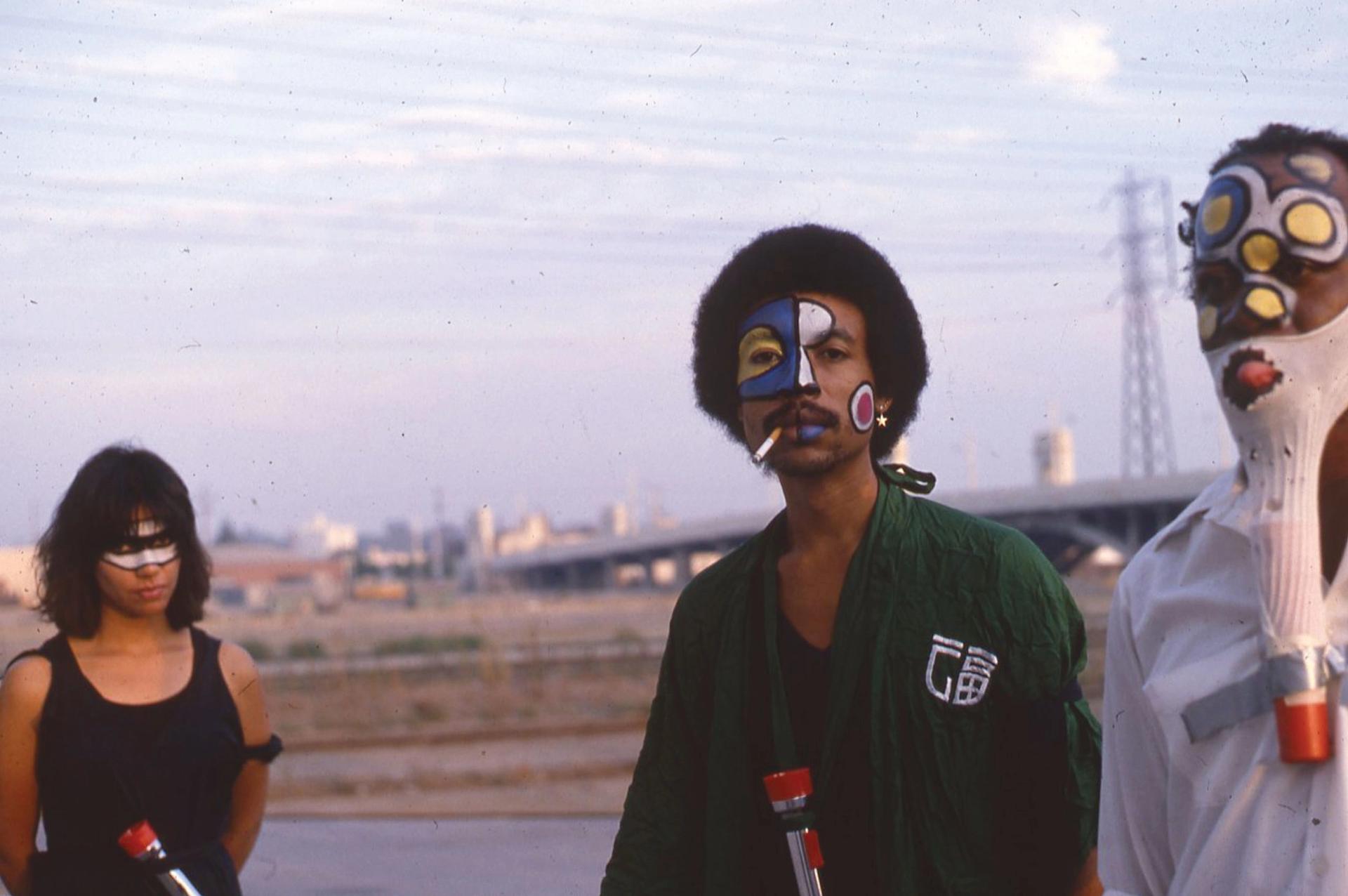

Participants rehearse for Without Your Interpretation (1984). Jenkins’s video works critique the representation of Black people in mainstream media Courtesy of the artist and The Hammer Museum

What inspired your shift from painting and mural-making to video work?

When I was making the Venice Beach mural, a friend of mine, who was also a painter, told me about this video workshop on the boardwalk. I was interested, in a sense, because I was interested in the rise of independent filmmaking in the 1960s-70s. Two films in particular that inspired me were Easy Rider and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. I caught the video ‘jones’ and ended up recording Remnants of the Watts Festival (1972-73) using a Portapak, the first portable video recording device. I thought the festival was misrepresented, and this was a chance to create my own visual expression. That footage received a lot of attention and still does, not surprisingly.

Your early videos, like Remnants of the Watts Festival, took a slightly documentary form. Mass of Images (1978)—the work you submitted to get into Otis—is one of the first works that were more experimental.

I became more interested in media and got a greater understanding of what Black filmmakers were making, and also how non-Black filmmakers were depicting the Black community. What I wanted to explore in graduate school was the Black image in Western art and how it had changed or not changed from the time of Rubens to the present. The servant context has been so prevalent in Western art and the mainstream. That work was my first comment on this idea; the early video art movement in general was defined by anti-media statements, and used as a vehicle for inserting ourselves into the media.

Video art wouldn’t gain wider recognition for several decades.

Choosing video as an art form meant entering into an ephemeral experience. When people talk about the “fine arts” and why it took a while for something to be recognised as art, people ignore that, as far as the market was concerned, you were making work that would not last. It’s not a three-dimensional object, or something that people would like to sell. The disadvantage of not being able to sell the art was an impediment for video artists. Unless you were Nam June Paik, no one paid attention to your work and would much less consider buying it. To some extent, that discrepancy still exists.

The title of the exhibition, Without Your Interpretation, is drawn from a work you made in 1983. What does it mean?

I had reached a point where I thought I had to tell the people who were not understanding my work that the work lives without your interpretation. Primarily because these people would not want to learn anything about the Black experience that I was commenting upon, and because they seem to not allow me to have a voice outside of the hood. I recognised the way they characterised and restricted what the Black voice could be in

the arts. It was proclaiming: “This work is without your interpretation because you seemingly don’t want to understand what I’m trying to say.”

• Ulysses Jenkins: Without Your Interpretation, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, until 15 May