Following runs at David Zwirner’s New York and London locations, a suite of paintings by the late, prodigious Noah Davis is coming home to Los Angeles. The show, curated by Helen Molesworth and Justen Leroy, is arriving at the The Underground Museum, an institution that Noah and his wife Karon Davis founded in the South Los Angeles neighbourhood of Arlington Heights in 2013, just two years before Davis died of cancer at 32. Though this will be his first solo exhibition of paintings at the museum, a number of works on view have spent time in the space before—they were painted there, back when Davis lived at the institution with his wife and their son, and when he and his brother, film-maker Kahlil Joseph, shared a studio in the space.

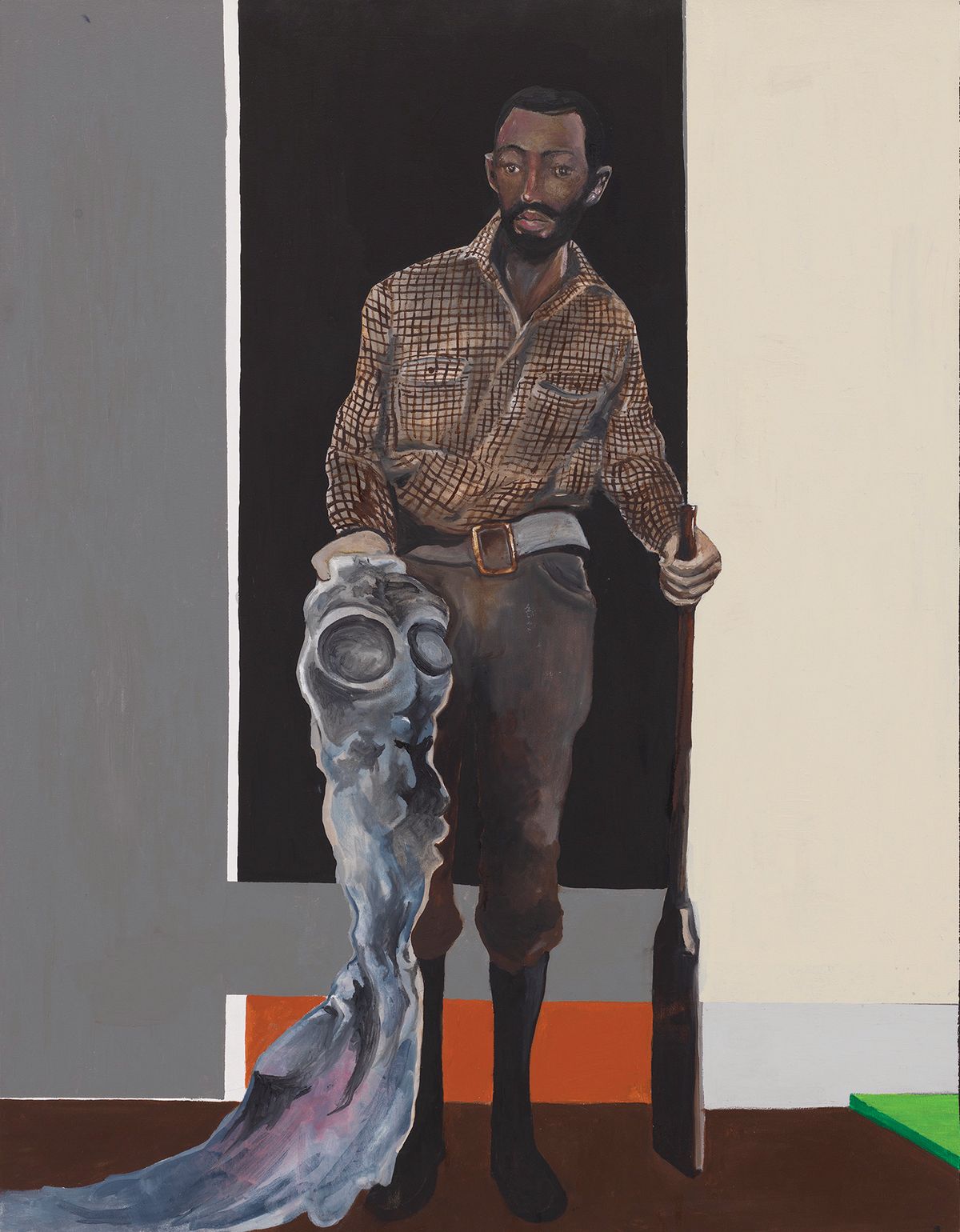

Davis’s paintings are primarily figurative, sometimes dipping into the surreal and other times languishing in the mundane, and most often occupying a space between the two—a realm of quiet magic in which the everyday is imbued with the infinite. “He was painting his daily life; he was a young man with a young wife and young child. He and Karon had a child early, and that was his life, and that’s what he was painting,” says Molesworth. “It’s doing what art does, which is taking something very personal and somehow offering it as universal, and there you are as the viewer, allowed to have your own space between the individual and the universal.”

In Untitled (Moses), a small 2010 painting of Davis’s son, we are given what may be the view from the artist’s eyes as he bathes his child in the sink. The baby, no bigger than a football or a hydrangea bulb, faces away from us, trying to squirm his way out of the bath. “He could’ve painted Moses six ways from Sunday: in Karon’s arms, walking toward his father, but he doesn’t, he paints the kid already trying to test his own boundaries and limits as a child,” says Molesworth. “He paints his child already moving away from him, and I find the emotional resonance of that really quite palpable in a lot of Noah’s paintings.”

Like the portrait of Moses, many of the works emphasise what Molesworth refers to in her catalogue essay as “the profound intimacy of being alone together”. She writes, “It’s as if Davis was reminding us that even when we are together—in love, in family, in community—we are also alone, existentially alone, and a large part of daily life is how we negotiate that aloneness with others.”

“It’s doing what art does, which is taking something very personal and somehow offering it as universal”

Helen Molesworth, curator

The works also contend with other things: with Blackness, with all that is involved in living an ephemeral life tucked into an ephemeral world, with the city of Los Angeles and with what it means to love and be loved. Just as every ode contains an elegy, every image here contains a swirling mixture of joy and sorrow that underlines the extent to which you cannot have one without the other.

“Certainly, in this suite of exhibitions, I was trying to introduce Noah’s oeuvre to what at that moment would become his largest ever public,” says Molesworth of her selection of paintings, which differ slightly between locations so as to best respond to the varying spaces: the cavernous West 19th Street David Zwirner hub in New York, the townhouse-style London showroom and now The Underground Museum for their homecoming. And as the paintings make their return to Los Angeles, a dialogue emerges between the images and the city in which so many of them take place. Take the Pueblo del Rio paintings, set amid the titular Paul Williams-designed housing projects, in which the sky is an enchanting shade of muted purple unique to Los Angeles, made possible by the city’s witching mixture of light and smog. “I think there’s a terroir to these paintings—if I can borrow a phrase from wine—and their relationship to Los Angeles light and Los Angeles feel,” says Molesworth.

It was no small undertaking to choose works from Davis’s catalogue raisonné—which is both shockingly vast and shockingly good for someone who only lived to 32. There were logical decisions, such as wanting to organise a show representative of a number of different series and styles, but also exploring how the paintings interact with each other so that, cumulatively, they might express a bit of the magic that was so potent in Davis. “It’s such an ineffable process,” says Molesworth, “there’s definitely a note of alchemy to it.”

- Noah Davis, The Underground Museum, until 30 September