Mary Corse and Helen Pashgian have come a long way since they were included in the exhibition Phenomenal a decade ago, easily the most ambitious exhibition to date of Light and Space artworks in the US. At the time of that show at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, both artists were largely seen as outliers. As women artists who were active in the 1970s making highly refractive paintings and glossy resin forms, respectively, they largely fell outside the feminist art tradition. And they seemed, because of their media and also their gender, to also fall outside the mainstream of the Light and Space movement, long-defined rather narrowly by the biggest ideas and most intangible artworks of Robert Irwin, James Turrell and, to a lesser degree, Doug Wheeler.

But that has begun to change. This winter, Pashgian has a major survey at Site Santa Fe following her autumn show in New York with Lehmann Maupin, which has brought recent, coloured resin spheres and one 1981 canvas with epoxy to Frieze Los Angeles. Meanwhile, three years ago, after extricating herself from Los Angeles gallerist Douglas Chrismas and signing on with Kayne Griffin, Corse landed both a major installation at Dia Beacon and a show at the Whitney Museum of American Art. (Kayne Griffin, soon to be Pace Los Angeles, has a new Corse painting from her DNA series featuring acrylic squares and glass microspheres in acrylic on canvas at Frieze.)

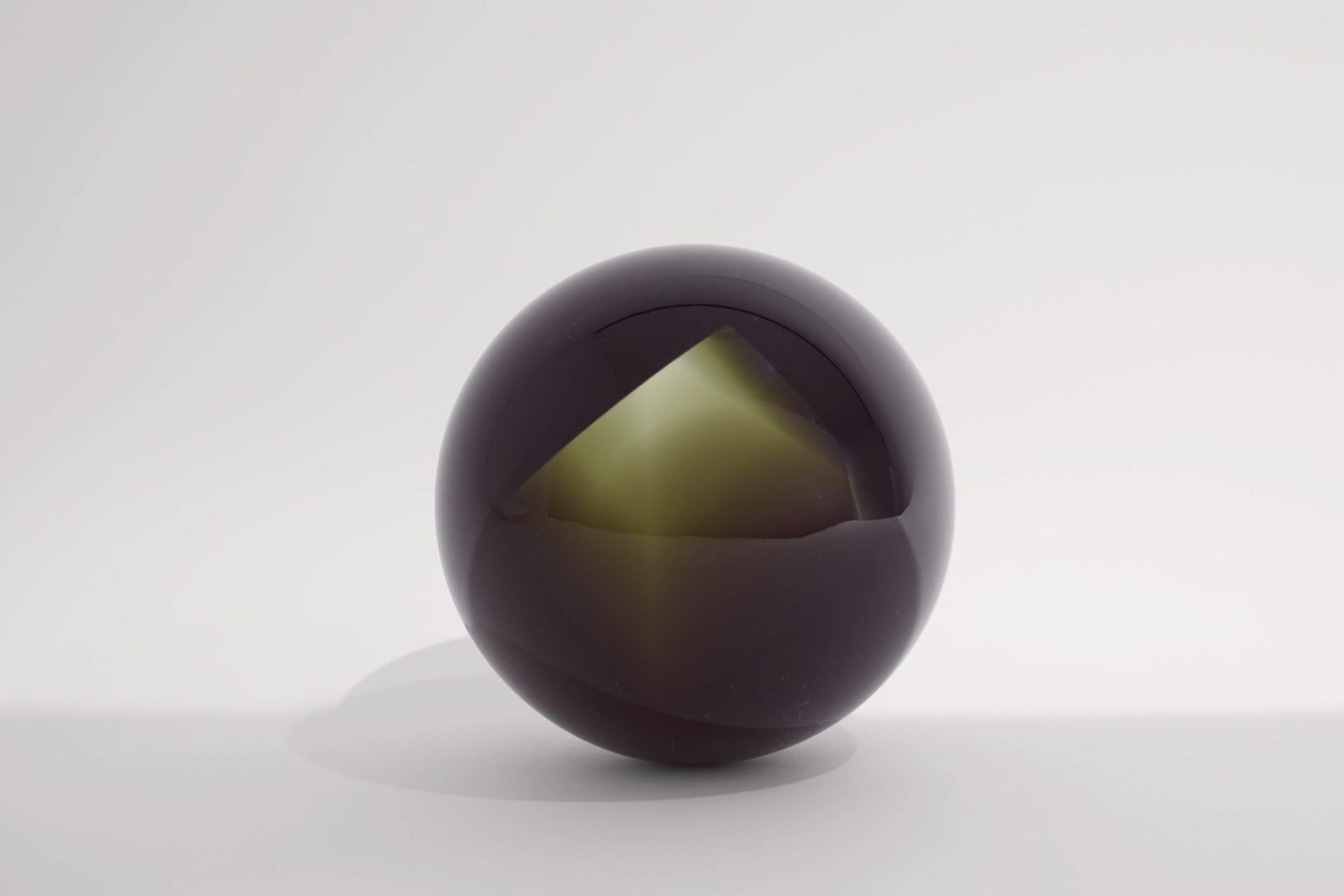

Helen Pashgian, Untitled, 2018 Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London

Something interesting happens when artists are rediscovered by the mainstream art world: they begin to change the very historical context that once excluded them. By recognising Pashgian, Corse and other women artists as central and not peripheral to the Light and Space movement, curators and scholars are forced at long last to rethink its core tenets. In particular, they are overturning the narrow idea that light must be the primary medium—“my material is light”, Turrell has repeatedly said—which relegates objects made in solid materials such as fibreglass or acrylics to some other form of Minimalism.

Some of this rethinking is coming from some 9,000km away, far from the Southern California. In its largest show yet, Copenhagen Contemporary has made the bold move of including Corse, Pashgian, Lita Albuquerque (for her ultra-pigmented work) and Judy Chicago (for her early smoke performances) under the Light and Space umbrella, as well as next-generation European artists such as Olafur Eliasson, Ann Veronica Janssens and Anish Kapoor. Museum director Marie Nipper also included lesser-known figures such as Elyn Zimmerman and Connie Zehr.

Elyn Zimmerman, Untitled, 1974 Courtesy the artist. Light & Space, Copenhagen Contemporary, 2021. Photo: David Stjernholm

“I was amazed I couldn’t find more women artists included in Light and Space exhibitions,” Nipper says. “We did a lot of research, read reviews from the time and found artists like Elyn Zimmerman, who once worked for Irwin and Turrell and was a secretary for Fred Eversley.” Zimmerman’s work in the show consists of eight large panels casting dynamic sets of shadows, a recreation from 1974, while Zehr has remade her 1972 undulating sand installation Eggs, which Nipper calls a sort of “organic minimalism”.

“Light and Space was more than these very industrial large-scale pieces, there was also a sensibility on a material level brought forth by the women artists who were working in sand and more organic materials,” Nipper said, though she was careful to note that a number of women used industrial materials, too.

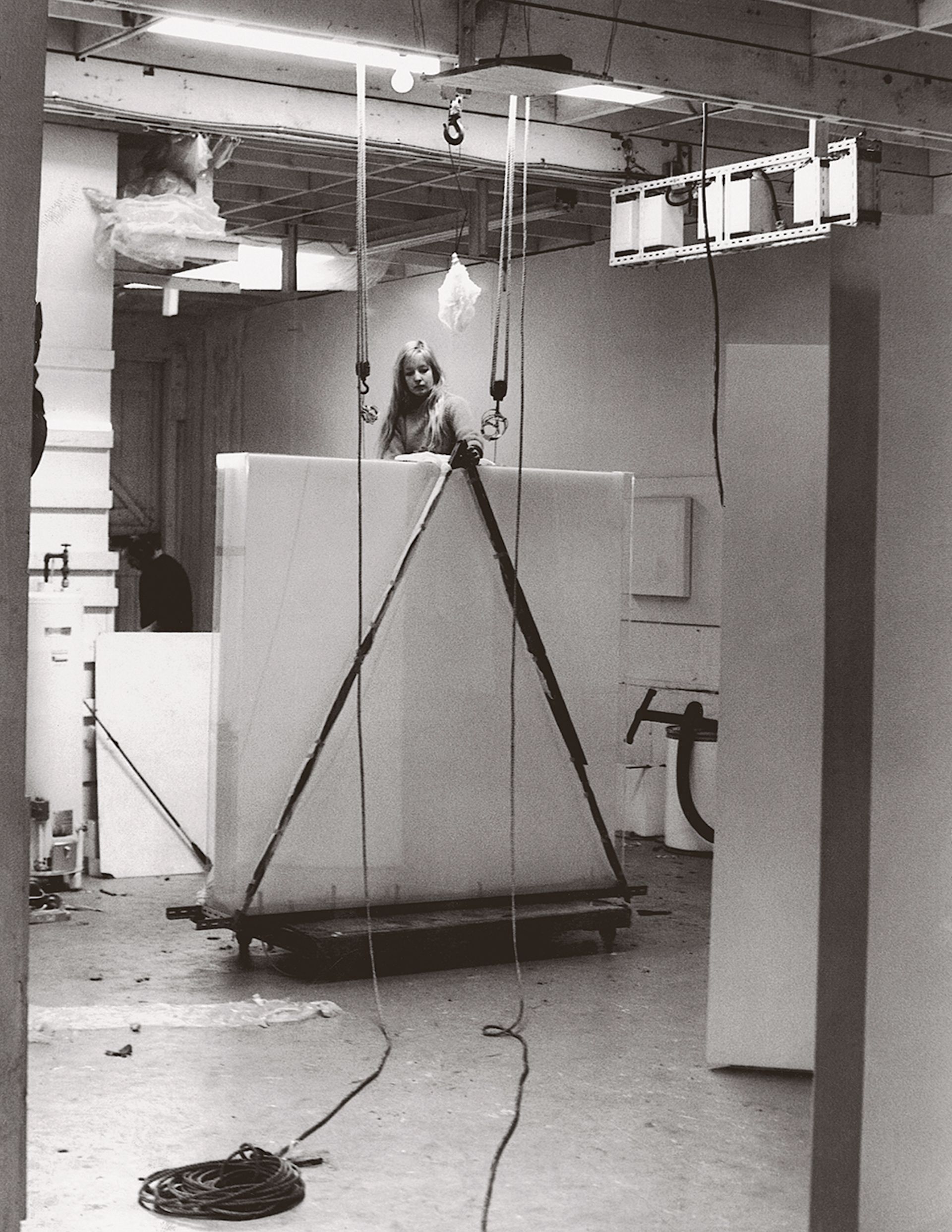

Mary Corse in her studio in Downtown Los Angeles with her light box work Untitled (1967) Photo via Wikimedia Commons/Bgeijer

Not everyone is on board. Most scholars still reserve the term Light and Space for works by a handful of artists working to escape medium-specificity, calling everything more durable Finish Fetish. Even a new travelling survey from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s collection, which includes Pashgian, Corse and Chicago, continues to make this distinction, with its title Light, Space, Surface cleverly bridging the two camps.

But Pashgian says the distinctions are not very useful. “What’s interesting about those separations is that they’re false—we’re all interested in the same things, light and perception, even when we approach it in different ways,” she says. “My newest works are objects but they dissolve very much like works by Irwin and Turrell.”

Pashgian says that the reverse is also true: the Finish Fetish label could apply to the whole group. “If you look at Doug Wheeler’s big scrim in Phenomenal, the surface on that is perfect,” she adds. “If there’s a little piece of dirt or a fly on it, that’s all we see, and we lose the exquisite beauty of looking through a volume of light.