In Johanna Demetrakas’s documentary about Womanhouse, the 1972 takeover of a dilapidated Hollywood mansion by the Feminist Art Program of CalArts, you can see Karen LeCocq sitting at an ornate vanity playing the role of the middle-aged courtesan Lea. She knows her looks are fading and painstakingly applies thick layer after layer of foundation in a desperate attempt to turn back the clock.

The irony is that LeCocq was only 22 at the time and entirely wrinkle free. Now, at age 72, LeCocq is reprising that silent performance a final time, with more lived experience to draw on. She will become Lea again on Friday for the opening of an exhibition organised by Anat Ebgi gallery called Womanhouse 1972/2022 (18 February-2 April) exploring the Feminist Art Program, its origins and its legacy.

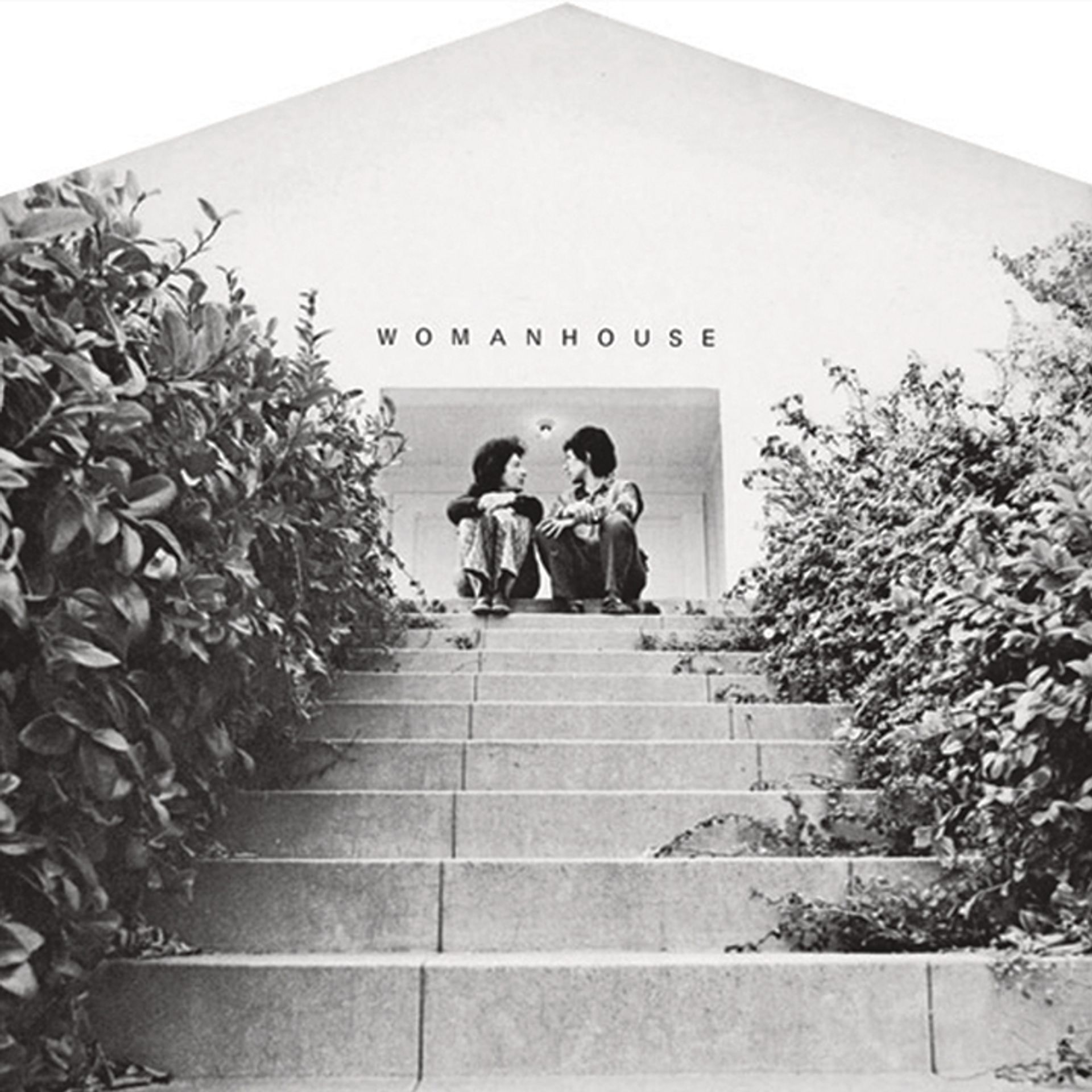

The catalogue cover for Womanhouse in 1972, designed by Sheila Levrant de Bretteville Photo: Sheila Levrant de Bretteville/Wikimedia Commons

When the doors of Womanhouse opened at 533 North Mariposa Avenue in Hollywood 50 years ago, art history cracked open a bit too. The month-long exhibition did for feminist art what the Société Anonyme exhibition of 1874 did for Impressionism and the Exposition Internationale of 1938 did for Surrealism, sparking public attention with sensationalist write-ups in magazines such as Time. But this was far from a surrealist funhouse: most of the artists, white but from different socioeconomic classes, were using the tropes of women’s work such as ironing, cooking and makeup rituals to expose domesticity as a symptom and tool of oppression. One visitor, Gloria Steinem, has said she could divide her life into before and after she saw Womanhouse, which showed her that “women have symbols too”.

It was a grossly overlooked part of art history because we were a bunch of women in Los Angeles and not a bunch of men in New York CityKaren LeCocq, artist

The project was born of necessity. When Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro began the Feminist Art Program at CalArts, the school’s new Valencia campus was not complete, so they had to work off-site. They decided to use a soon-to-be-demolished 17-room house in Hollywood with broken windows, no plumbing and no heat as their studios and exhibition hall. Students worked together for weeks clearing rubbish, replacing and glazing windows and painting walls, while also developing their art and their confidence as artists. With group sessions that Chicago calls content-searching and others call consciousness-raising, the programme was so physically and psychologically demanding that alumnus Mira Schor compares it to boot camp. “It was very intense—unlike anything I had ever experienced before,” she says, “and I made sure never to experience exactly that again.”

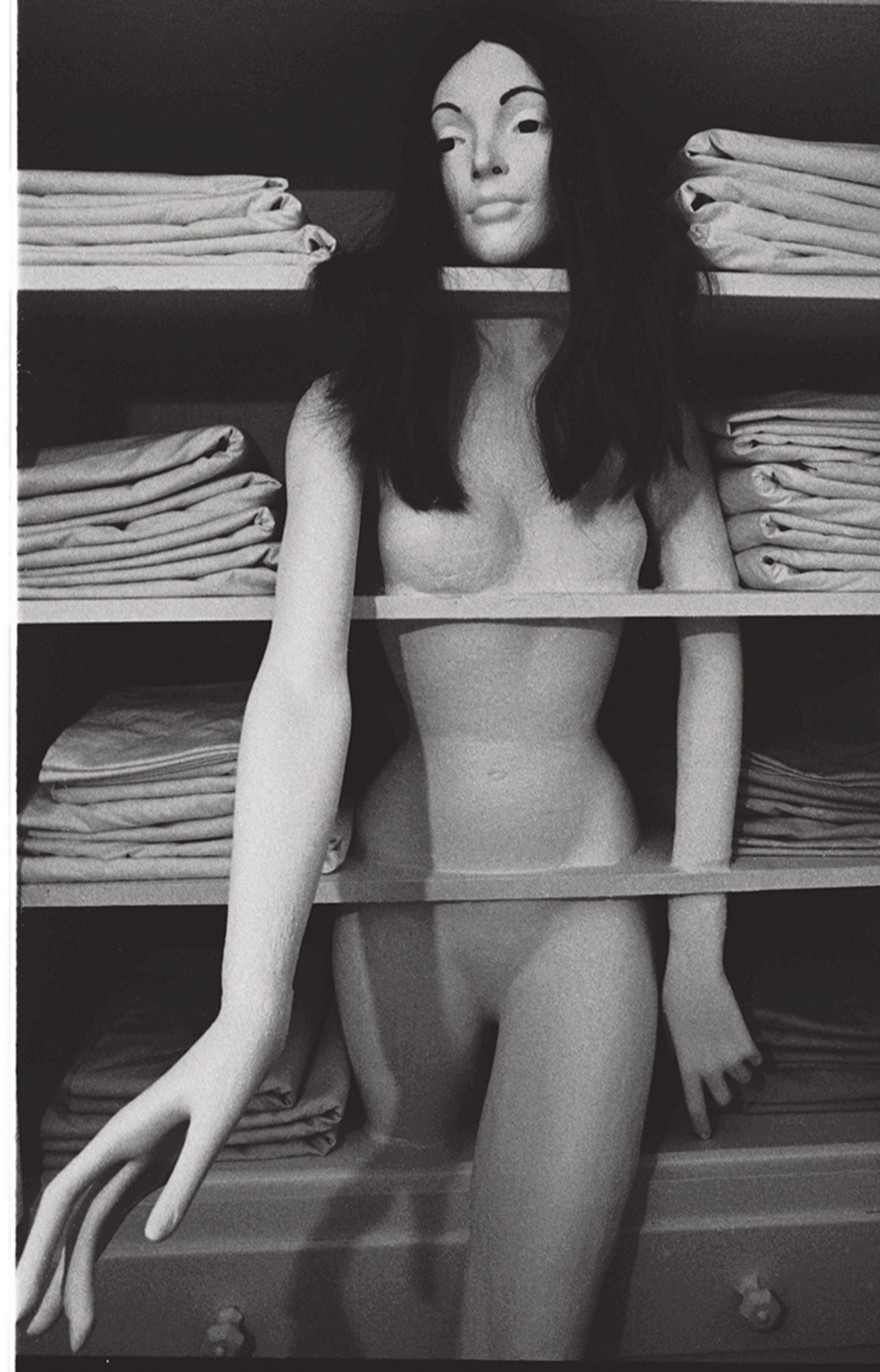

The installations were also intense. Sandra Orgel built a female mannequin into a linen closet so that the shelves bisected—and imprisoned—her body. Faith Wilding created what was popularly known as the “Womb Room”, a webby crocheted environment inspired by indigenous brush huts. LeCocq and Nancy Youdelman created Lea’s Room, inspired by the novel Chéri (1920) by Colette: a Victorian-style, antique-laden bedroom featuring a canopy bed draped with lace and that dressing table with its sea of antique glass bottles. “We tried to make it beautiful but suffocating at the same time,” Youdelman says.

A mannequin is imprisoned in Sandra Orgel’s Linen Closet from Womanhouse Photo: Dori Atlantis; courtesy of Anat Ebgi gallery

For one bathroom, Robbin Schiff created a vulnerable sculpture in a bathtub depicting her own body made almost entirely out of sand (the face was cast). In another, Chicago loaded the shelf with menstrual products and stuffed a rubbish bin full of bloody-looking pads, viewable only through a white scrim. There was also an ambitious performance schedule on the weekends, with Wilding improbably switching gears each night from wearing the big penis in Chicago’s Cock and Cunt Play to playing the paragon of feminine passivity in her own celebrated monologue Waiting.

Womanhouse was, in short, a matrix for much of the full-body installation art and performance work we see today. But it was not a game-changer for most of the artists involved. LeCocq, for one, says she took Womanhouse off her resumé for years when applying for teaching jobs because it scared away employers. “I think it was a grossly overlooked part of art history because we were a bunch of women in Los Angeles and not a bunch of men in New York City,” she says. Youdelman says the biggest misconception persisting today is that it was “only a student project” when it was so ambitious in scale and content.

Schiff, who now works in book publishing as an art director, says, “When I came back to New York the next year, no one had heard about Womanhouse and I felt no one seemed to care too much about feminism in art schools or in day-to-day life.” Her colleagues at Random House today do not know about her Womanhouse connection either.

Faith Wilding and Jan Lester in a performance of Judy Chicago’s Cock and Cunt Play at the house Photo Courtesy of Though the Flower Archives; © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

These days not a lot is left of Womanhouse from a material standpoint beyond photographs, the film by Demetrakas and a documentary that Lynne Littman made for KCET-TV. The house was demolished after the show and most of the installations were scrapped as well. Apart from the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston (which owns a re-creation of Wilding’s Crocheted Environment) and the Smithsonian American Art Museum (which has the original Dollhouse by Schapiro and Sherry Brody), few museums have bothered to show or reconstruct work, making the Anat Ebgi show all the more important.

For the show, LeCocq is recreating a small section of Lea’s Room, setting up an antique dressing table with some original touches such as velvet red curtains and antique perfume bottles, where she can reprise her role. The gallery also has some works related to Womanhouse, including a 1971 painting by Schor that contains some motifs found in her Red Moon Room painting in the house—a low-hanging moon, a solitary woman and a chequerboard-patterned floor. (Schor saved one of the original panels and placed it with family friends when she left CalArts, but she has not seen it since.)

For the run of Womanhouse 1972/2022 the gallery has also planned a performance programme in collaboration with Los Angeles Nomadic Division (Land) that involves local artists restaging 1970s performances and will hold a number of consciousness-raising sessions.

“Why am I doing this? Because museums aren’t,” says the show’s curator, Stefano Di Paola of Anat Ebgi. He calls it “an institutional-level show that I am trying to do in three months instead of three years”.

A 2022 perspective

Chicago is also stepping in to make sure this moment of history is not forgotten. Along with recreating the Menstruation Bathroom in her Through the Flower exhibition space in Belen, New Mexico, this summer, she is inviting artists of all genders from the state to participate in a new version of Womanhouse to take place in a “perfect 1950s house” nearby. (Youdelman is co-ordinating the project.) Chicago calls it “Wo/Manhouse” to “emphasise the fact that the installation will approach the subject of the home and domesticity from a 2022 perspective rather than 1972 perspective”.

Chicago has only recreated her Menstruation Bathroom once before, in 1995 for the exhibition Division of Labor, which travelled from the Bronx Museum of the Arts to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Wilding also redid Crocheted Environment for that show, and that version is now in the Boston museum.

Clearing out Womanhouse, 1971 Image courtesy of Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries

Wilding says the original Womb Room, a destination for selfies before the term existed, was stolen. “When we went on the last day to close up Womanhouse, it had been cut where I nailed the rope into the floor. It was gone and it never reappeared. To this day we don’t know what happened to it.”

As for smaller works, such as the moulded foam breasts and fried eggs by Vicki Hodgetts that covered the kitchen walls, Wilding remembers a big sale at the end of the exhibition. “A lot of people have bits and pieces of Womanhouse,” she says. “It’s all scattered.”

• Womanhouse 1972/2022, Anat Ebgi gallery, 4859 Fountain Avenue, Los Angeles 90029, 18 February-2 April