A new play about Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat opens tonight at the Young Vic theatre in London. Starring Paul Bettany as Warhol and Jeremy Pope as Basquiat, the play has been written by Anthony McCarten, screenwriter of recent, acclaimed biographical films The Theory of Everything (Stephen Hawking), Darkest Hour (Winston Churchill), Bohemian Rhapsody (Freddie Mercury), and The Two Popes (Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis), and is directed by the Young Vic's artistic director Kwame Kwei-Armah.

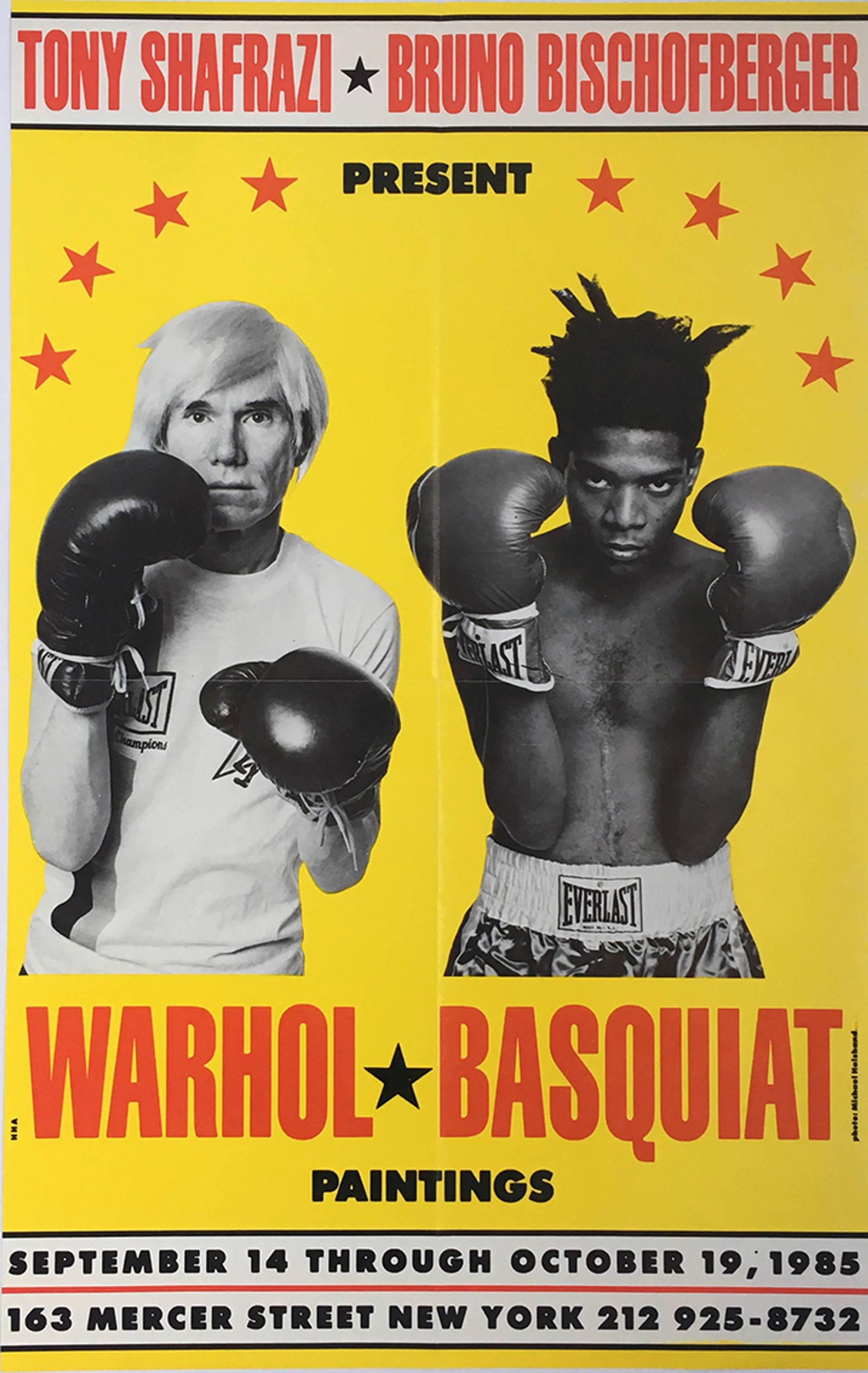

The play focusses on the three years, near the end of both artists’ lives, when they collaborated on a series of paintings for a 1985 show at the Tony Shafrazi gallery in New York. On one side Warhol, the Pop art superstar, desperate to maintain his hold on the cutting edge of art. On the other, Basquiat, the explosive new talent who made his name as a graffiti artist on the streets and imbued his canvases with a spiritual power that was anathema to Warhol’s celebration of the superficial. Two visions of art and two huge personalities collide and briefly coalesce in McCarten’s play, at turns both hilarious and heartbreaking, as the artists challenge and provoke one another before slowly revealing themselves. McCarten has also adapted the play into a film which goes into production later this year with the same cast and director as the play. We spoke to him during a break in rehearsals last week.

TAN: After Stephen Hawking, Freddie Mercury, Winston Churchill and two popes, why did you want to write about Basquiat and Warhol? And why this particular moment in their lives?

Anthony McCarten: I knew both their stories reasonably well, as much as anyone who is interested in art. But it was not until March 2019 that I was in New York and happened to find that there were two major retrospectives happening at the same time: the Basquiat show, a private exhibition [Jean-Michel Basquiat at the Brant Foundation] and Andy Warhol at the Whitney [Andy Warhol—From A to B and back again] and in the same day I saw both shows and walked from the Lower East Side to the Whitney, which is on the other side of Manhattan, through Andy and Jean’s old haunts.

The combination of the atmosphere and the huge divergence in the styles of the two artists and the knowledge that for three years they’d put aside their artistic, stylistic differences and collaborated on a series of paintings, it made me think: ‘there’s a drama there’.

I’d just come from doing a play and a movie about two popes who were diametrically opposed: one was a conservative, one was a liberal and I’m in a period right now where I’m very interested in dialogues, I’m interested in people who, on paper, are polar opposites who have to find common ground. I wondered what that would be between these two men who, famously, never said ‘boo’ when you turned the camera on. If you watch interviews with Andy, he barely says more than ‘Gee, that’s great’ or ‘wow’, and I smelled a rat. These are personas; underneath there were living, breathing, funny, witty sorrowful people, real human beings. So, I wanted to bring an audience into that closed room with Jean and Andy to which we’d not previously been privy. And that’s what I’m interested in doing right now, creating rooms where we can eavesdrop on a side of a person that we haven’t seen before.

Anthony McCarten in rehearsals with the two lead actors, Paul Bettany and Jeremy Pope © Manuel Harlan

TAN: Andy Warhol’s words in your play come close to things he famously said but are not his actual words. Is that correct?

AM: By and large, yes. There are some direct quotes from Andy in the play; some of them are from his diaries. We have the blessing of the Warhol Foundation and that’s always important to me. Not that I am doing the bidding of either estate, quite the opposite; hagiography is a lie. But I have found in the past 15 years that I’ve been doing a lot of portraits that estates are very willing to take risks with their prized possessions and to hold them up for close examination, warts and all, because the public demand no less. I got permission to use excerpts from the diaries from the Warhol Foundation and I used maybe ten lines. They so captured Andy’s tone of voice that I wanted them in there.

TAN: There is such a wealth of material out there about Warhol, where do you start and stop the research?

AM: There is a point beyond which research is not helpful and can be unhelpful because it can constrain your imagination. This play is a work of the imagination, it’s my interpretation. But it also wants to be based in reliable research; nobody is interested in the story of a famous person that’s highly invented; it has to have its feet anchored in reality. My job is to fill in the bits where there is no record of what they did on these days or what they thought about these issues, so I have to engage in inspired speculation. It’s not idle fancy, it’s not just my best guess, it has to be based in solid research.

We have a duty to those we do portraits of to be truthful. To be truthful means to work from the known facts, but not to be entirely constrained by them because if you’re just doing the facts, you’re just doing biography; it’s not art. There’s a wonderful story of Picasso painting Gertrude Stein’s portrait: she sat for many, many days and he wouldn’t show her the canvas. Finally, he said: ‘I’m done’ and she came round to his side and looked at the canvas and said: ‘I don’t look like that at all'. He replied: ‘No, Gertrude, but you will’, meaning there is a role for the interpreter. The interpreter can see things that the sitter can’t necessarily see or hasn’t allowed themselves to see.

In both Jean’s and Andy’s case, they were both protective of their intimate selves and they were very careful not to give anything away. They had different reasons for being protective. In Andy’s case, he thought it was bad for business. He learned early that it was better to just encourage people and say things like ‘oh, gee’ and that would get the most amazing response out of the public. Like a Minimalist, Andy realised that the less you gave, the more you got back.

I think Jean was quiet because he was carrying the huge cultural weight of being a Black artist in a white American art scene at that time. And he really was on his own there and had to play by other people’s rules. And that’s costly; the strain of living up to expectations in a cultural environment that isn’t your own, I think, accounts for Jean’s ongoing drug use and, perhaps, early death.

An exhibition poster for Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat's joint show at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery © Michael Halsband

TAN: Basquiat’s 1983 painting Defacement—which memorialises the death of Michael Stewart, an artist beaten to death by New York policemen for writing graffiti in the subway—plays a key part in your story. Why were you interested in it?

AM: Because it shows how spiritual Basquiat was as an artist and his view of art as a reclamation of spirit or belief that it could be incantational, it could have supernatural power. Defacement was an act of reviving or returning his lost friend to us. I thought that was important because more than any other painting of Jean’s that I’ve seen, it’s the easiest one to interpret what he was trying to do which is to convey his outrage at what had happened. It shows this extreme point of difference from any of Andy’s works. For Andy, life was all about surfaces so art that reflects that was truthful in his book. He was at pains to say that art was increasingly all about surfaces too and it was dishonest to make art that claimed to be anything else. Defacement became a key work for me because it shows Jean at the extreme end of the vision of what art can and should do.

Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat, Stoves (1985) © 2022 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts; Inc./The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat; 2022

TAN: In his recent biography of Warhol, Blake Gopnik described his collaboration with Basquiat as a failure both artistically, because the works they made together weren’t very good, and commercially, because none of them sold when they were shown at the Tony Shafrazi gallery.

AM: Blake is right to this extent, when they were shown at Tony Shafrazi’s gallery, not a single one sold at the time. But that’s the story of art, it’s non recognition in the moment and then there’s a re-evaluation later. You’d have to be a very wealthy individual to buy one of those paintings now so, commercially, they weren’t a failure. Their styles were not a natural fit, but I find them interesting for that reason. The fact that Andy was interested in logos and Jean was interested in this symbolic, passionate explosion of graffiti-like signs and these two styles were laid on top of each other. They are not a natural fit but as a record of this period and of this unprecedented collaboration that happened, I think they are unique in art history. I would dearly love to own one. I’ve seen some of them and I disagree with Blake, I think they’re incredibly powerful. To see this two-car pile up of styles is very challenging but incredibly exciting to look at.

• Anthony McCarten’s The Collaboration is at the Young Vic in London until 2 April

• To hear an interview with Anthony McCarten and Kwame Kwei-Armah listen to the forthcoming episode of our The Week in Art podcast, released on Friday