“Did you know babies can fly?” Sherry Turner DeCarava says with a smile.

The art historian and widow of Roy DeCarava—who died in 2009, aged 89—refers to a meditative image, one of 66 currently on display at David Zwirner’s London gallery (until 19 February). It is the first exhibition dedicated to the artist in London in over three decades.

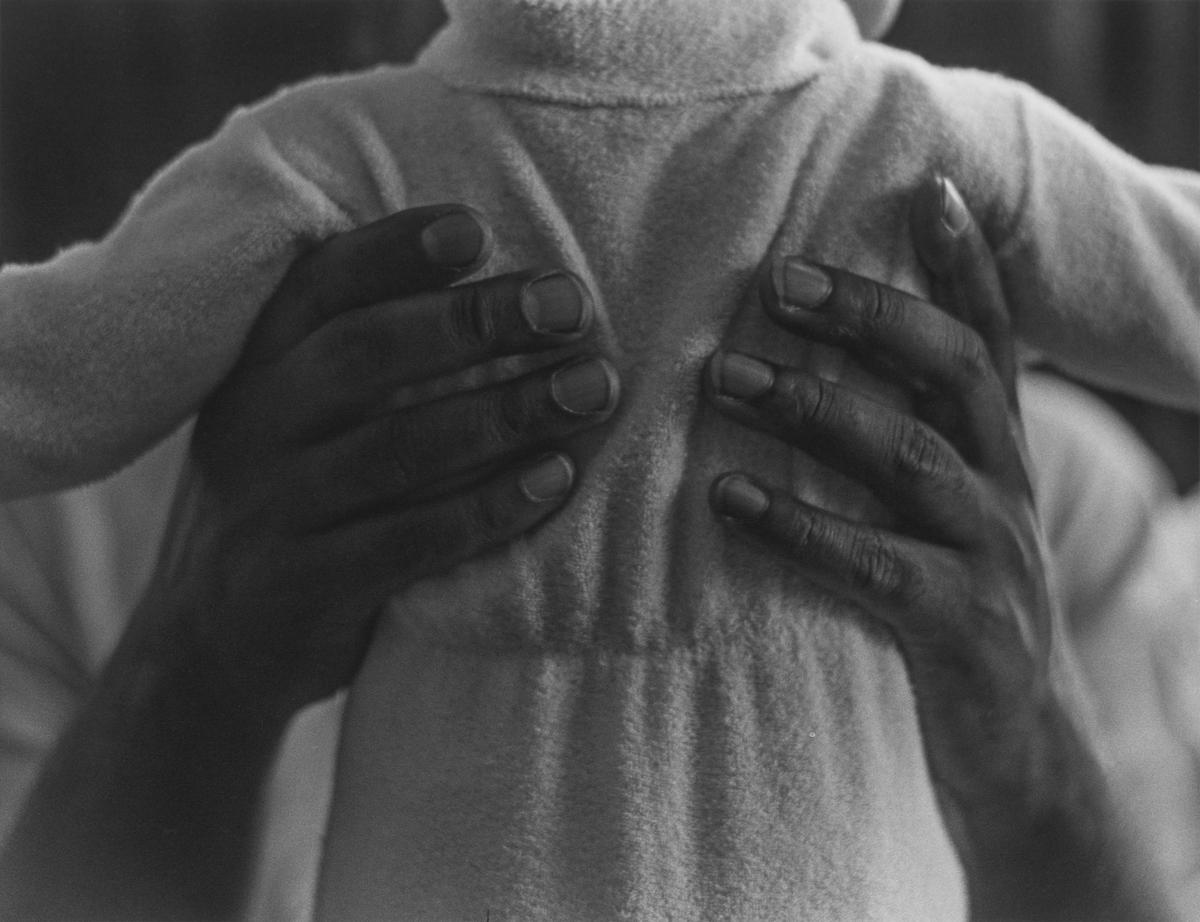

In the picture, Bill and son (1962), a man’s hands grip the body of a newborn, dressed in a fluffy romper. The gesture seems to be both a warm proclamation of life and the beginning of a battle between parent and child. Like many of DeCarava’s works, it is both universal and immensely personal—presenting, as the artist once said, “a moment so profoundly that it becomes an eternity”.

As Turner DeCarava suggests, what you see is not always what is in the frame—in this case, the image is tightly cropped so that neither the man nor the baby (a friend of DeCarava and his son) are identifiable. And the baby may not be where we think it is: the vitality that emanates from DeCarava’s work is attention.

“When we think about a portrait, we think about a picture of a face—and we accept the face as representing the person. But he saw other qualities as the portrait," Turner DeCarava says. "And if the baby is being held like that, it is because it is wiggling, even if we don’t see it—and that wiggle is the future. We see the tessellation of the man’s own babyhood in that future life—in the end, or in the beginning, we all have the potential to come together.”

Roy DeCarava, Six figures in sunlight, 1985 © The Estate of Roy DeCarava. All rights reserved Courtesy David Zwirner

Turner DeCarava first met the late artist in the 1960s when working at the Brooklyn Museum, where she invited DeCarava to give an artist’s talk. They married in 1970, and Turner DeCarava has worked tirelessly to preserve and contextualize DeCarava’s work, shedding light on his many contributions to the shape of contemporary art over 60 years; from his breakthroughs with silver gelatin printing techniques to his insistence on the value of photography as an art form.

“It was a meeting [made] in heaven”, Turner DeCarava says. “He tended to turn people down, he didn’t like to speak about his work, but he did speak to me. No one was writing about his work, and this was a puzzle to me as it was so deserving. So I kind of filled this space that should have been filled with the work of others, and gradually was.” Turner DeCarava now handles the artist’s archives and estate in New York.

DeCarava’s own journey began during the Harlem Renaissance. Born in the neighbourhood in 1919, at five years old he decided he wanted to become an artist. He went on to study art at Cooper Union and the Harlem Art Center and then worked as a commercial artist. He began to take photographs as references for his paintings, but by the late 1940s devoted himself to photography.

Roy DeCarava, Horse and rider under tree, 1987 © The Estate of Roy DeCarava. All rights reserved. Courtesy David Zwirner

It was not the easy road to take—in the 1950s and long after, photography was still a burgeoning art form with little commercial or institutional recognition or interest and DeCarava found himself engaged in “a decades-long struggle to insist his work was treated as art, that was his critical and central posture vis-à-vis the importance of photography”, Turner DeCarava says. His first institutional solo exhibition came almost 20 years after he started to take pictures, at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1969.

DeCarava believed in the potential of photography, but one of the artist’s great achievements is that he continually transcended the medium. It’s not the photograph that leaves an impression on the viewer, but the careful choreography of grey tones and forms—abstracted but not obliterated—that perform an evocative dance with the subconscious.

“Curators often want to talk about photography as a style, but he really makes another argument," says Turner DeCarava. "Each image is a world unto itself, he did not do something that was replicable as a style or an approach, or Black art—it was far more complex that labels allowed him, and in fact he says [in the short documentary film Conversations with Roy DeCarava, 1983] that he welcomes the labels, but he needs them all—and more.”

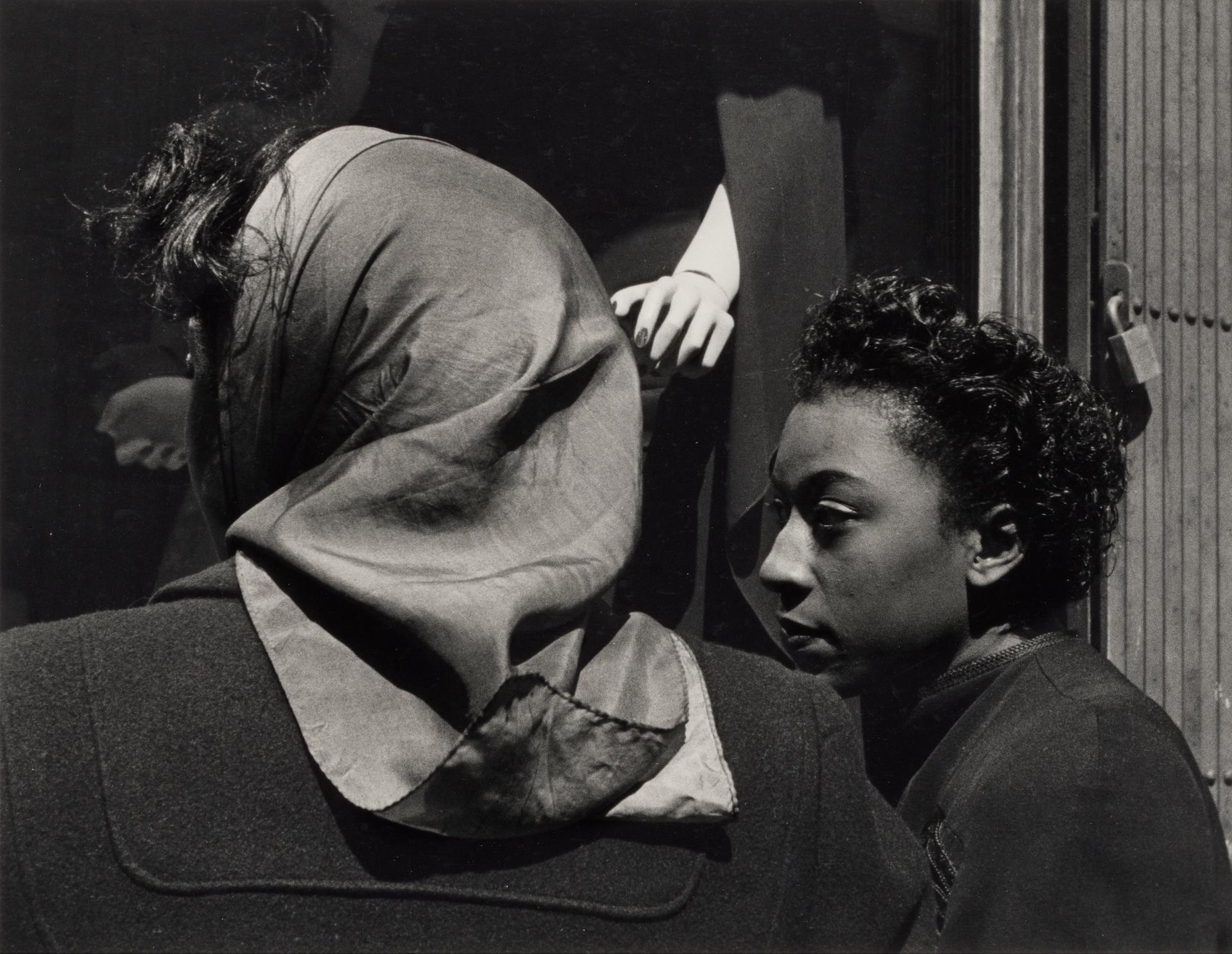

Roy DeCarava, Two women, mannequin’s hand, 1952 © The Estate of Roy DeCarava. All rights reserved. Courtesy David Zwirner

Existing in the “and more”, DeCarava moved freely between subjects. He photographed people, often in motion—the famous jazz musicians that often garner the most attention among his oeuvre, manual labourers, parents, pairs, couples; he photographed places, particularly the texture and tapestry of the urban environment, moving between scintillating sun and the beguiling symmetry of its immovable architecture. Although rooted in reality, DeCarava produced images that were hard to locate, and that always left physical space, lacunae—“he left room for the audience, room for people to come in”, says Turner DeCarava.

In a remarkable work, Hallway (1953), the viewer is plunged directly into the inky obsidian of a long, ominous corridor. “He establishes a line somewhere in that space that you can enter through. The visual line is an art effect, but it is also an emotional effect,” Turner DeCarava says.

The image is also autobiographical. “He had grown up in these impoverished hallways in New York, and they were terrifying to him as a child," Turner DeCarava says. "Here he was, late at night, passing by the hallway once again, but seeing it in a whole different way; the light was so diffuse, and he found himself in a strange position of finding something really ugly and scary, but suddenly beautiful, too—that contradiction provoked him into a state of celebration.”

A photograph from 1957 posits another key issue that orbits DeCarava’s work. Striking and raw, Man’s Back turns a man’s body into a canvas on which we encounter “a life lived".

"This is really breaking new ground in American art, and I would say in world art," Turner DeCarava says. "He was capable of blending all of these abilities together in a realistic manner that really communicates value and importance of a human being”.

Roy DeCarava, Donald Byrd, 1962 © The Estate of Roy DeCarava. All rights reserved. Courtesy David Zwirner

DeCarava’s work is often addressed primarily through his position as a Black man in the US, and as a chronicler of everyday Black life in America in the second half of the 20th century. DeCarava himself was acutely aware of how such interpretations might limit the work and emphatically opposed social documentary photography. He felt a different strategy was needed to tackle inequality in his country. His work searches for moments of euphoria and epiphany in the everyday, the culmination of states beyond our control that reflect our fundamental humanity.

“Part of this issue floats around the question of what does one do with injustice, with anger—how do you process that as a personal experience, in life and as an artist?” Turner DeCarava says. “Roy was quite distinct from other people I’ve met; he was, I would say, serene. He had this sense of homeostasis, this level-quality in his perception of the environment and the things that happen in life. He had a righteous anger but not bitterness, that was oriented towards justice. These two qualities existed in relation to each other, and they informed that balance that he achieved for himself personally and in the work.”

DeCarava’s personal experiences may have shaped his empathetic eye from early on, but he also looked to artists such as Vincent van Gogh, Caravaggio, José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros and Käthe Kollwitz for their treatment of the human figure and their expressions of the human condition. Like those artists before him, he remains one of the great humanists of our times.

“He celebrated the individual and this was part of the importance of his work," Turner DeCarava says. "He had this sense of humanity, this feeling for people.”

- Roy DeCarava: Selected Works, until 19 February, David Zwirner, London