The Cuban-born artist Carmen Herrera has died, aged 106. Herrera was known for her precise, radiant geometric works centred on “crisp lines and contrasting chromatic planes”, says Lisson Gallery, who represented the artist since 2010 and confirmed her death. "She died peacefully in her sleep at her apartment and studio in New York, where she had lived and worked since 1967, for much of that time with her husband Jesse Loewenthal, who also died at home in 2000," the gallery said in a statement.

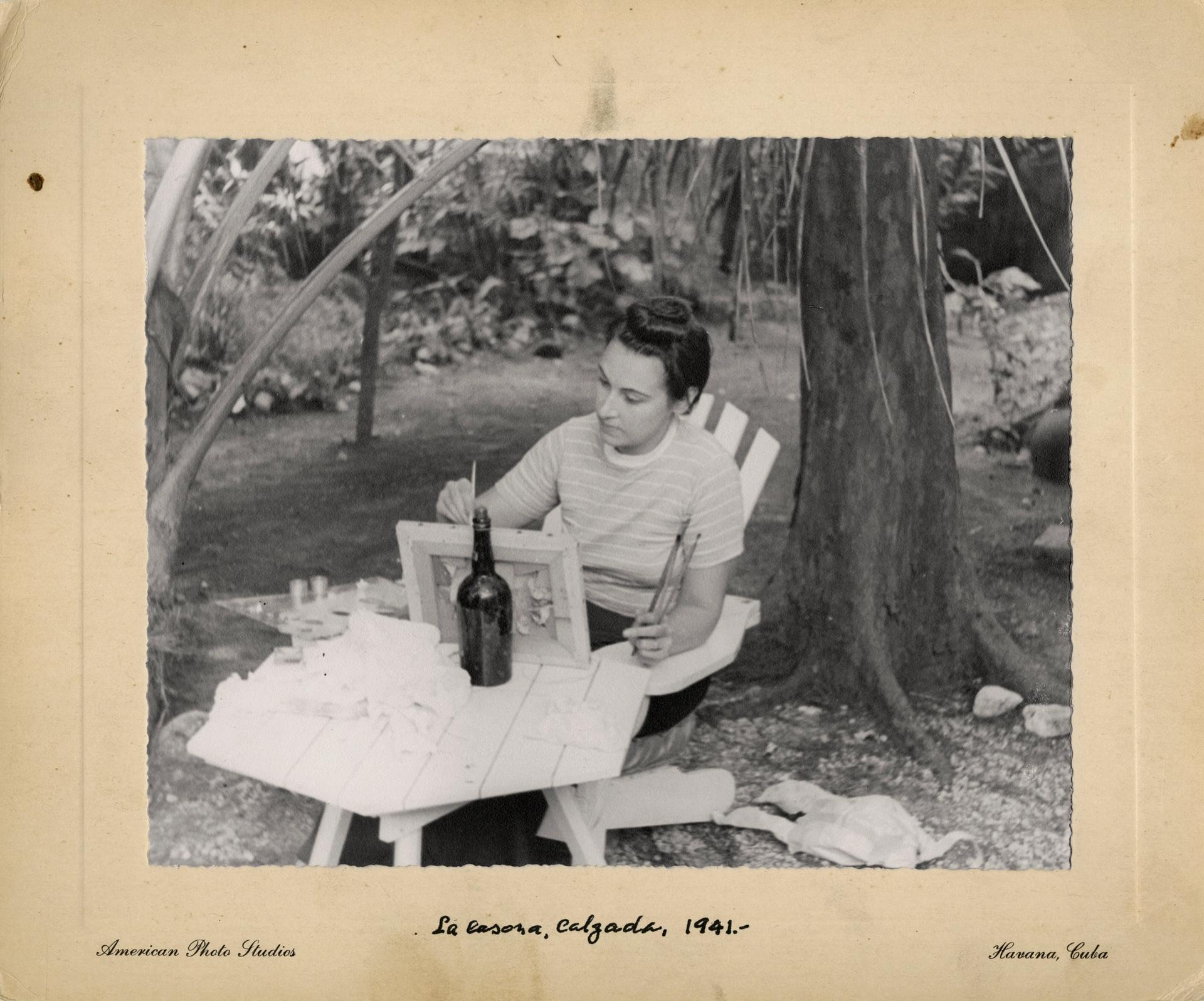

Carmen Herrera in Havana in 1941. Photo: Jesse Loewenthal. © Carmen Herrera. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

“Such an extraordinary artist, such an extraordinary life,” wrote Donna De Salvo, the senior adjunct curator at New York’s Dia Foundation, on Instagram. “She was a pioneer, a trailblazer, a radical painter and with recognition has become a source of inspiration for artists around the world,” says Alex Logsdail, the chief executive of Lisson Gallery, on social media. Herrera once said: “There is nothing I love more than to make a straight line. How can I explain it? It’s the beginning of all structures really.”

How Herrera was overlooked until much later in life is often mentioned in analyses of her life story, highlighting how the patriarchal art world sidelined gifted women artists. Herrera’s work was shown in a mid-career survey at the Alternative Museum, an artist-run space in New York, in 1984. Her profile was boosted in 1998 when the Museo del Barrio in New York hosted the exhibition The Black and White paintings 1951-89. Other key shows took place at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, UK (2009) and at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York (2016).

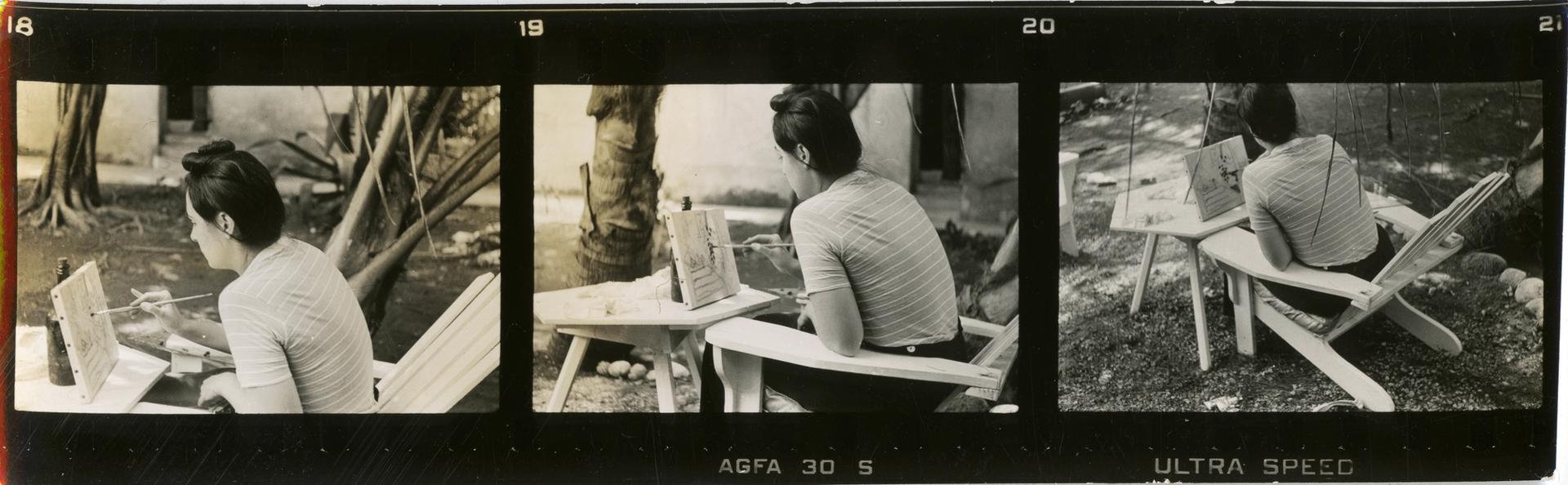

Carmen Herrera painting in 1941. © Carmen Herrera. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

"Carmen Herrera’s exhibition at Ikon in 2009 exemplified a serious commitment to hard-edged abstraction, insufficiently appreciated in preceding years," Jonathan Watkins, the director of Ikon, tells The Art Newspaper. "Her wonderful paintings and sculptures, filling our entire building, were a refreshing revelation, bringing this artist’s extraordinary talent to the attention of a wider world. We were lucky to be working with someone who was at once aesthetically uncompromising and so generous."

Carmen Herrera in her studio in Paris (around 1948-53) © Carmen Herrera. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

Herrera’s career and commercial standing was transformed at the age of 89 after her work was shown in an exhibition at the Latin Collector Gallery in TriBeCa, New York in 2004. The art critic Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times that Herrera’s “declarative, witty, hard-edge style has points of contact with Mondrian, Ellsworth Kelly and Op Art, but is most immediately connected to the vanguard Neo-concrete work of artists like Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica who flourished in Brazil after World War II”.

Herrera was born in Havana in 1915 where her father founded the El Mundo newspaper and her mother was a journalist and founder of a feminist group. She was sent to school in France, before returning to Cuba to begin a degree in architecture at the La Universidad de la Habana in 1938. She met her future husband, the academic Jesse Loewenthal, during her studies; after their marriage they moved to New York in 1939.

Carmen Herrera and Jesse Loewenthal in front of the Eiffel Tower, Paris, sround 1948-53. © Carmen Herrera. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

It was only after the couple moved again, to Paris in the years following the Second World War, that she began to paint in her recognisable, definitively abstract style, shifting from figuration and representation, as part of the Salon des Realités Nouvelles, an art association founded in Paris in 1939.

Carmen Herrera with Jesse Loewenthal in 1977. Photograph: Kathleen King © Carmen Herrera. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

On returning to New York in 1954, she could not get a dealer. In a 2015 documentary made by Alison Klayman (The 100 Years Show), Herrera relates the story of a woman gallerist who told her she was a better painter than many of her starrier male contemporaries but there would be “no show because you are a woman”. The artist said: “I walked out of the place as if someone had struck me. A woman to a woman?”

In an interview with the Guardian in 2016, Herrera further described how women were shut out of the art scene “because everything was controlled by men, not just art. I knew [the painter] Ad Reinhardt and he was terribly obsessed with Georgia O’Keeffe and her success. He hated her. Hated her! Georgia was strong, and her paintings were exhibited everywhere, and he was jealous.”

“While her position as a Latina woman may have ghettoised and slowed her early career in New York, Herrera’s plight came to represent the lost generations of many forgotten modernist practitioners, only some of whom have begun to receive their art historical dues,” adds Lisson Gallery.

In the past two decades, Herrera received long-overdue recognition. Her works can now be found in several permanent museum collections, including the Guggenheim, Abu Dhabi; the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, DC; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Museum of Modern Art, New York and the Tate, London; among others.

Carmen Herrera visiting Estructuras Monumentales, an exhibition by the Public Art Fund in City Hall Park, New York, on 25 September 2019. © Carmen Herrera. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

In July 2019, an exhibition of Herrera’s Estructuras Monumentales was organised by the Public Art Fund in New York’s City Hall Park, which then travelled to Houston’s Buffalo Bayou Park in 2020. She also received several awards: she was made an Honorary Royal Academician by London's Royal Academy in 2019; in 2020 she was named a National Academician by the National Academy of Design in New York and in 2021 she was awarded the prestigious Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the Ministry of Culture in France. She was chosen for two major mural commissions in the past two years, for the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas, and the Manhattan East School of Arts in Harlem, New York.

"Even in 2022, Herrera was in the process of planning for future projects, among them a ballet with Wayne McGregor at the Royal Opera house in London and two exhibitions at Lisson Gallery in New York and [at the future venue in] Los Angeles, the first of which was due to open just before her 107th birthday," a gallery statement adds.