Reports of unauthorised excavations by an unknown group in parts of Afghanistan’s Bamiyan Valley, as well as rapid development in the area, have concerned locals and heritage experts.

A Unesco World Heritage site, it was once the home of the sixth-century monumental Bamiyan Buddha statues—known as Salsal and Shahmama—that were carved into the rock face until, in 2001, the Taliban blew them up. In 2003, the area was put on Unesco’s World Heritage in Danger list. Now rapid building work and digging under the new rule of the Taliban, combined with environmental factors, are contributing to the speedy destruction of the Bamiyan Valley and its heritage.

“We carried out a damage assessment of the 2001 explosions, which illustrated that cracks of up to 30 metres had formed through the depth of the cliff,” says Ghulam Reza Mohammadi, the former Unesco provincial coordinator for Bamiyan who had to be evacuated to Germany in August to escape the Taliban for fear of persecution. “Excavating [now] during the winter months could see snow and water get inside the caves and into the existing cracks causing their expansion and creating a valley, which will cause the eventual collapse of the entire cliff,” he tells The Art Newspaper.

Outside groups take advantage of site

A source with close ties to the Taliban's Ministry of Information and Culture who spoke on condition of anonymity because of fear of retaliation, confirmed that excavations have taken place in two separate locations. The first was within the cliff above the Salsal Buddha’s niche, set back around 40-50 metres. The second excavation was in the ground by the base of the Buddha. Both areas are known to contain buried caves, some of which had never been opened before.

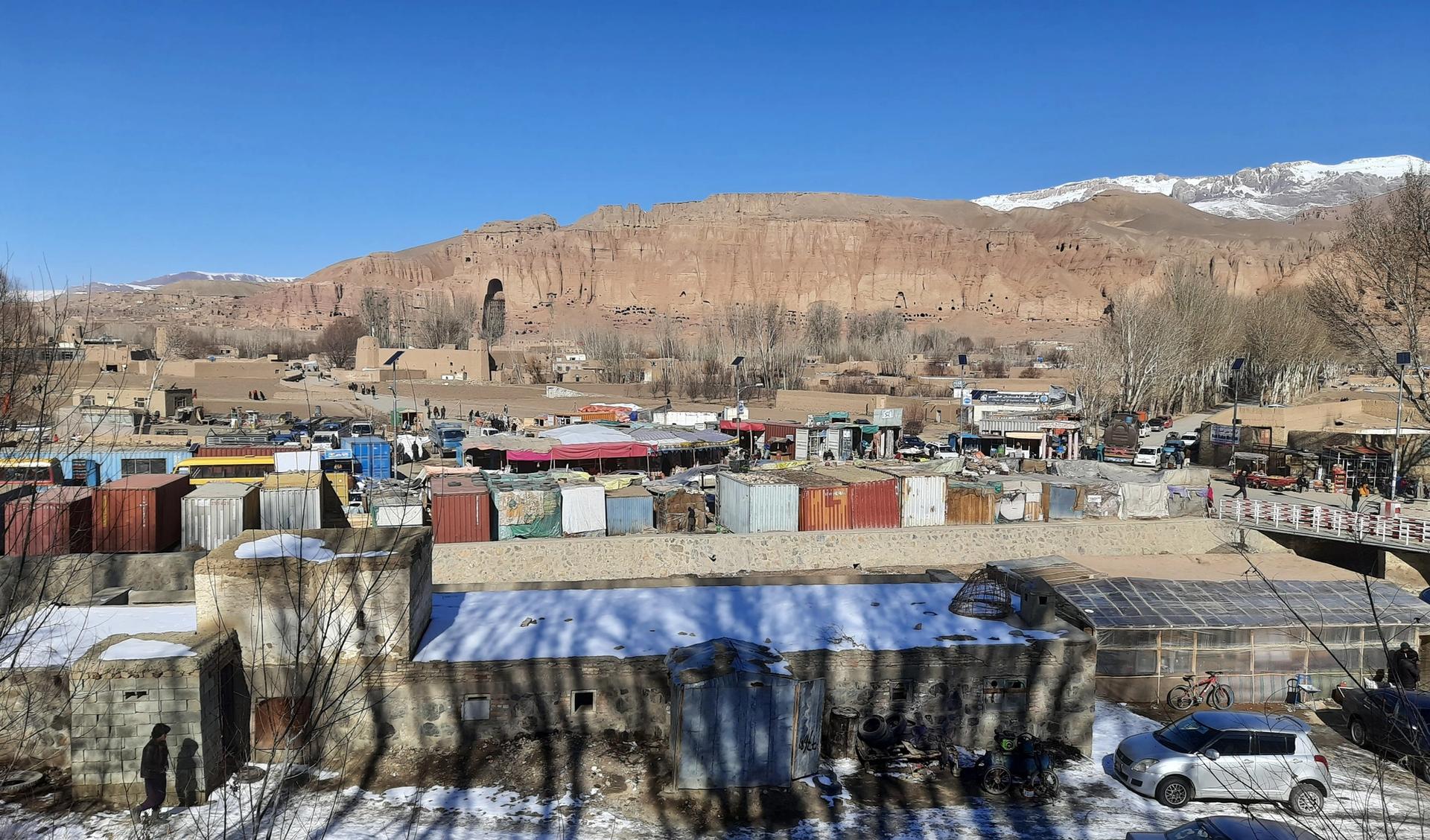

Taken in 2022, this photo shows how the area a few metres away from Salsal Buddha’s niche has been transformed into a coal depot. Heavy vehicles drive through the listed valley to reach the depot and off load their cargo. A cemetery that dates back to the Kushan dynasty (first to third centuries) is said to be in this location. Photo: © The Art Newspaper

Mohammadi suspects that the people who carried out the excavations were international smugglers who could have only gained access to the area with the Taliban’s support. “They opened caves that had not been opened and we didn’t know what was in them, so no one knows what they found,” he says. “These were people with archaeological knowledge, familiar with Bamiyan’s geography. They had expertise in excavation and they knew exactly where the caves were located. It shows they are international smugglers, most probably from Pakistan.” According to Mohammadi’s reports, people who witnessed excavating said that the group was speaking Urdu, a claim that was repeated by the anonymous source close to the ministry.

Two Bamiyan residents with in-depth knowledge of the heritage site confirmed to The Art Newspaper that the area had been closed to the public for the duration of the excavations. They observed that the ground above Salsal Buddha’s niche was disturbed and new soil was present in the area, all signs of recent digging.

The Taliban’s Bamiyan governor, Mullah Abdullah Sarhadi, confirmed that there had been excavations in the area to the German news outlet Deutsche Welle, which first reported on the illegal excavations on 28 January. Sarhadi then backtracked on his comments and denied that there had been any digging in a local television interview this week. He had not responded to a request for comment at the time of publication.

Mohammadi explains that for any excavation to take place at a Unesco World Heritage site, a detailed plan of the works must be presented to the World Heritage Centre and if the work is approved it can then be carried out under their supervision.

Growing urban developments take over

Meanwhile, The Art Newspaper has learned that the regulations that once protected the Bamiyan site have been abandoned since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan on 15 August 2021, placing Bamiyan Valley on a path to complete destruction.

A coal store has popped up a few metres from where the giant Salsal Buddha once stood and it is slowly growing. Heavy vehicles travel through the valley to bring it stock daily, stopping on listed ground. Nearby, French archaeologists had discovered a cemetery dating back to the Kushan dynasty (first-third centuries), Mohamammadi says.

Taken in 2022, this photo shows developments that are prohibited by Bamiyan’s Cultural Master Plan have popped up on listed grounds, including new homes, loading bays, shops that sell car parts, wood, food and coal, taking over the listed landscape. Salsal Buddha’s niche can be seen in the background. Photo: © The Art Newspaper

“These vehicles are heavy and create vibrations, which are extremely dangerous for an already fragile site. That’s why they were not allowed here,” says the anonymous source with ties to the ministry. According to the Cultural Master Plan drawn up by Afghan authorities with Unesco’s guidance in 2007, the listed lands, including the landscape, cannot be built or traded on.

The lands were in the process of becoming government property through compulsory purchases but the procurements were not finalised before the Taliban takeover. As a result, the deeds to the lands are still held by private individuals who have used the opportunity to start building. Now new homes and shops have been constructed on the valley’s protected land, disturbing not only the scenery but also what remains of the buried ancient town.

Mohammadi says other protective measures such as the removal of snow from the cliffs or clearance of water canals and irrigation systems to prevent flooding of the area, are also not being followed by the new authorities.

Left vulnerable to looting

The site has also experienced vandalism and looting, much of which took place amid the chaos that followed the early days of the Taliban takeover in 2021. Two depots that housed treasured artefacts, one located near the Salsal Buddha and the other next to the Bamiyan Cultural Centre, were raided.

A buddha’s head estimated to be worth $100,000 and coins that are thought to be more than 1,000 years old are among the stolen items, according to the ministry source and another anonymous source with direct knowledge of the stolen items. The source close to the ministry says that the Taliban blames the previous employees of the Ministry of Information and Culture for the thefts, but they deny it. “Everything is gone. Now we have to watch and see in which international collection they are going to turn up,” Mohammadi says.

Barriers and gates that blocked access to the heritage site that contained delicate gold paintings, buddha statues, stupas and other precious remains were also vandalised and broken, leaving the remains and caves completely exposed and unguarded. “We installed gates to protect these sites. Now, there are no guards and no locks. Anyone can remove one of these beautiful paintings with a simple tool like a screwdriver,” Mohammadi says.

His concerns are shared by other Bamiyan residents who say they feel helpless. “Looking at the Bamiyan Valley today, it is difficult to imagine that this place was a beautiful historic site at one point,” says a Bamiyan local who asked to remain anonymous. He adds that there is no one to hear his or the other residents’ concerns as the Taliban appear to have approved the developments. He also suspects that the Taliban holds large stakes in the valley’s growing coal business.

“This area does not belong to Bamiyan, it belongs to the world. I would like to ask the international and cultural organisations to prevent any further damage to this area. Bamiyan is a cultural city, it is not the industrial city that it is being transformed into,” pleads another resident, who also wishes to remain anonymous for his safety.

Mohammadi echoes their concerns and offers a stark warning: “What remains in Bamiyan, the niches and the cliff, will collapse in the next ten years if the current mismanagement, unplanned excavations and disorder continues. It is a very realistic view and we should not fool ourselves otherwise.”