The acquittal last month at Bristol crown court of four protesters, found not guilty of causing criminal damage after toppling the city’s statue of slave trader Edward Colston in June 2020, has polarised heritage and culture professionals in the UK. Arts and legal commentators say that the verdict has many implications, with the trial reigniting the debate about the value of contested colonial-era public art works. More historic statues could now be vandalised, says the UK sculptor Nick Hornby.

Rhian Graham was accused alongside Milo Ponsford, Sage Willoughby and “others unknown” of helping to tie ropes around the statue’s neck that were used to pull it to the ground. Jake Skuse was accused of rolling the statue to Bristol Harbour. The four pleaded not guilty to the charges during the trial.

In the wake of the trial, the independent We Are Bristol History Commission group has published its report on the future of the Colston statue. The Colston Statue: What Next? document, which was commissioned in September 2020 by the Mayor of Bristol, Marvin Rees, includes a survey carried out while the statue was on show at the M Shed museum in Bristol.

Almost 14,000 people responded with 74% of all respondents saying that the statue should be housed in a Bristol museum while 65% support adding a plaque to the original plinth. Just under half of all respondents (49%), and nearly 58% of those from Bristol, support using the plinth for temporary works or sculptures. The report subsequently recommends that “the Colston statue enters the permanent collection of the Bristol City Council Museums service” and crucially that it is “preserved in its current state” (it remains marked in graffiti and damaged from the protests).

The report adds: “We recommend that the statue be exhibited, drawing on the principles and practice of the temporary M Shed display where the statue was lying horizontally. We recommend that attention is paid to presenting the history in a nuanced, contextualised and engaging way, including information on the broader history of the enslavement of people of African descent.”

Four protesters were found not guilty of causing criminal damage when they toppled Edward Colston’s statue Finnbarr Webster/Getty Images

‘Offensive, abusive and distressing’

The statue was toppled during a Black Lives Matter protest, following the murder of George Floyd by the ex-Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin in May 2020. The 18ft-high bronze statue had long divided opinion in Bristol. Colston was a member of the Royal African Company, which dominated the West African slave trade. The slaver, who was also a generous philanthropist, died in 1721 though the statue was erected in 1895. The battered and graffitied sculpture has since been on show at the M Shed museum in the city.

Steven Cammiss, an associate professor at Birmingham Law School, sat through the entire ten-day trial along with two other academics. Their report on The Conversation website states that one of the key defence arguments centred on preventing the crime of public indecency. “It was Edward Colston and Bristol City Council that appeared to be on trial. The defendants and multiple witnesses argued that Colston’s crimes were so horrific that the continued presence of his statue was offensive, abusive and distressing. The local council’s failure to remove it, despite 30 years of petitions and demands from Bristol’s African Caribbean community, in particular, also led to the defence claiming that the council’s inaction amounted to misconduct in public office.”

Cammiss says that contextualising the statue in the appropriate way could have prevented the work from being removed. “What really came through in the evidence was the extent to which the community’s disquiet with the Colston statue, in essence, just hit a wall.” A plaque was due to be added to the plinth in 2019, explaining Colston’s involvement in the slave trade. According to the Independent newspaper, an initial text put forward by a local historian said Colston had played “an active role in the enslavement of 84,000 Africans, including 12,000 children, of whom over 19,000 died en route to the Caribbean and America”. But alternative wording, proposed by the Bristol’s Society of Merchant Venturers, emphasised Colston’s charitable acts. This was vetoed by Rees, who felt that the text had been watered down. “If the text had not been hijacked by the society, I think most people in Bristol would have been satisfied and the statue may not have come down,” Cammiss says.

The explanation should be as big as the problem statue, in the same place... A QR code or polite plaque is not good enoughHew Locke, artist

Whose explanation is it, anyway?

So was the verdict the right one? “In the circumstances of that statue in that city, and what happened historically, I think [the verdict] was the correct decision,” Cammiss says. “Contextualising could have made a difference; with that lack of activity, I think it was a justifiable verdict. We should hesitate to question the verdict of a jury that has been properly directed in the law and has heard all the evidence.” A UK curator, who preferred to remain anonymous, however, called the verdict “perverse”, adding that jurors ignored the irrefutable evidence of criminal damage.

The Colston verdict has intensified the debate around the UK government’s “retain-and-explain” policy. Who, for instance should own the explaining, and how prominent should it be? A new heritage board, whose members include Trevor Phillips, the former director of the Equality and Human Rights Commission, and the historian Robert Tombs, is in the process of drawing up appropriate guidelines.

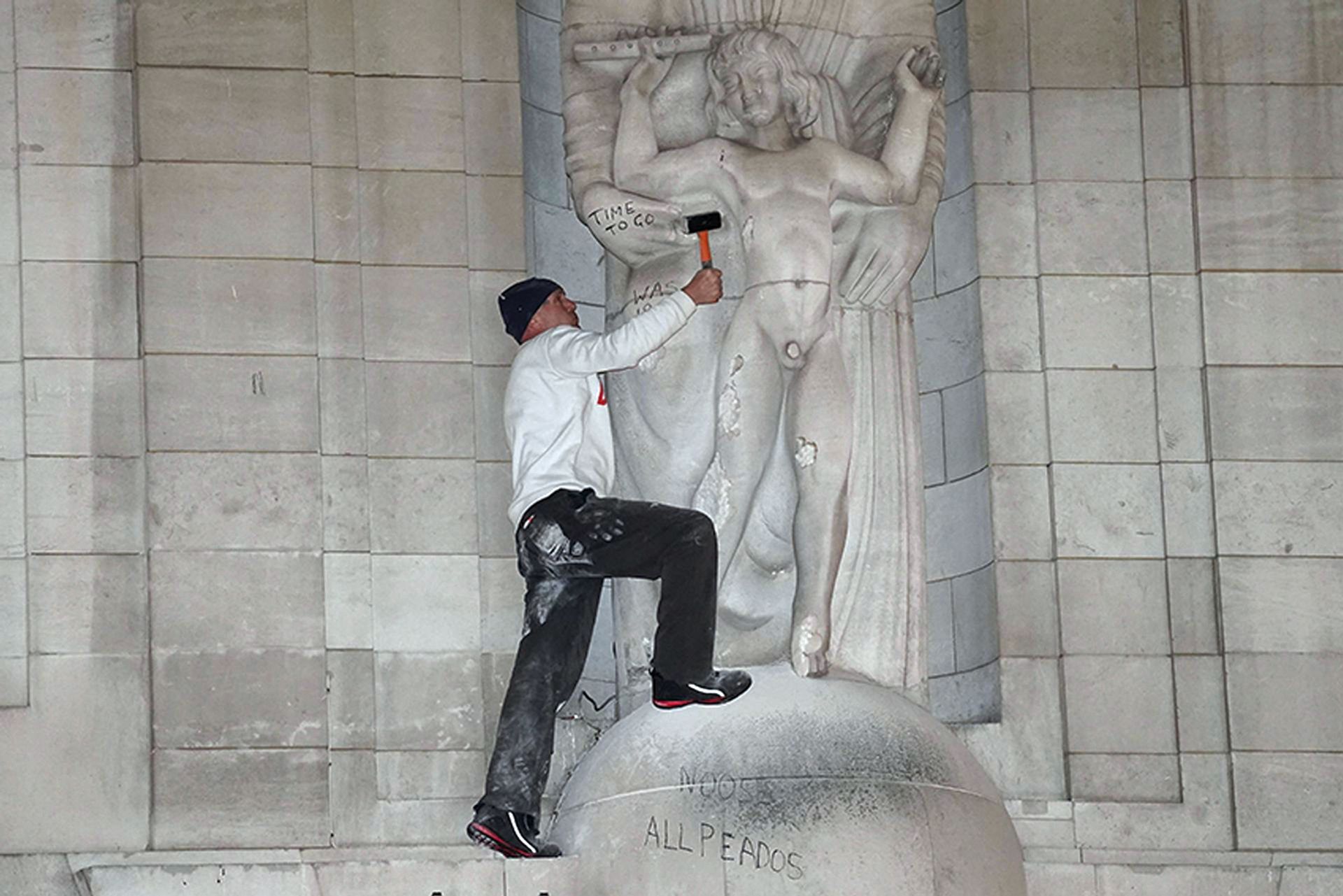

Last month a man was arrested after climbing onto Eric Gill’s statue of Prospero and Ariel outside the BBC’s headquarters in central London and attacking it with a hammer © PA Images/Alamy Stock Photo

The lobbying organisation, the Public Statues and Sculpture Association (PSSA), is adamant that the government’s plan is the right one. “The government should double down on this approach and ensure public sculpture is protected and valued,” say co-chairs Joanna Barnes and Holly Trusted. But the artist Hew Locke, who has made works focused on problematic statuary, asks what the “retain-and-explain” policy actually means in practice. “In my opinion the explanation should be as big as the problem statue, in the same place and as permanent as the statue. Otherwise it just sweeps the problem with a statue under the carpet. A QR code or polite plaque is not good enough,” he says.

The verdict has also opened up complex debates about criminal damage of public art on ethical grounds after a man was arrested last month for attacking Eric Gill’s sculpture, Prospero and Ariel, installed on the front of the BBC’s Broadcasting House headquarters in central London. Gill, who died in 1940, is well known as a paedophile who left details in his diary of his “sexual abuse of his daughters, sisters and dog”, according to a biography on the Tate’s website. Commentators have questioned how far his life should affect our judgment of his work.

“The case of Eric Gill is complex,” says Nick Hornby. “I think there is a very clear distinction to be made between representation of something immoral, and the immorality of an artist. It is not simple. As #MeToo comes for Picasso—and I think quite rightly so—I remain in awe of his artistic genius. As an artist and gay man, there are huge realms in the world who would deem my life as immoral.”

Buildings and monuments are listed for preservation by Historic England on the strength of their historic and architectural interest, and their artistic quality is one of the many factors that can contribute to their designation. Simon Hickman, a principal inspector for Historic England, was also called to the witness stand at the trial of the Colston Four.

The PSSA also points out, meanwhile, that most artists behind such contentious works tend to be forgotten in the furore. Irishman John Cassidy incidentally created the Colston work and was only mentioned “a couple of times” in court, Cammiss says.