“You can’t just put a tree on a building and say it’s green architecture,” says Vietnam’s leading exponent, Vo Trong Nghia (born 1976), although, from the evidence of this handsome edition, it is a practice to which he is not wholly averse. Here Vo’s projects are divided into two volumes, “Green” and “Bamboo”, each equipped with a short introduction by the tireless Philip Jodidio.

Vo’s interest in sustainability—nurtured while a student of the Japanese architect Hiroshi Naito—is set emphatically in the context of his Buddhist faith, which would appear to be devout (his staff have to meditate for two hours a day). But trees aside, Vo’s work also offers a fresh perspective on the Western modernist tradition of “organic” architecture: a cocktail of informal, function-led planning, a fluid dialogue between internal and external space and a somewhat romantic relationship with landscape that can be seen in the houses of C.F.A. Voysey, Frank Lloyd Wright (himself strongly influenced by the buildings he saw in Japan), Jørn Utzon and others.

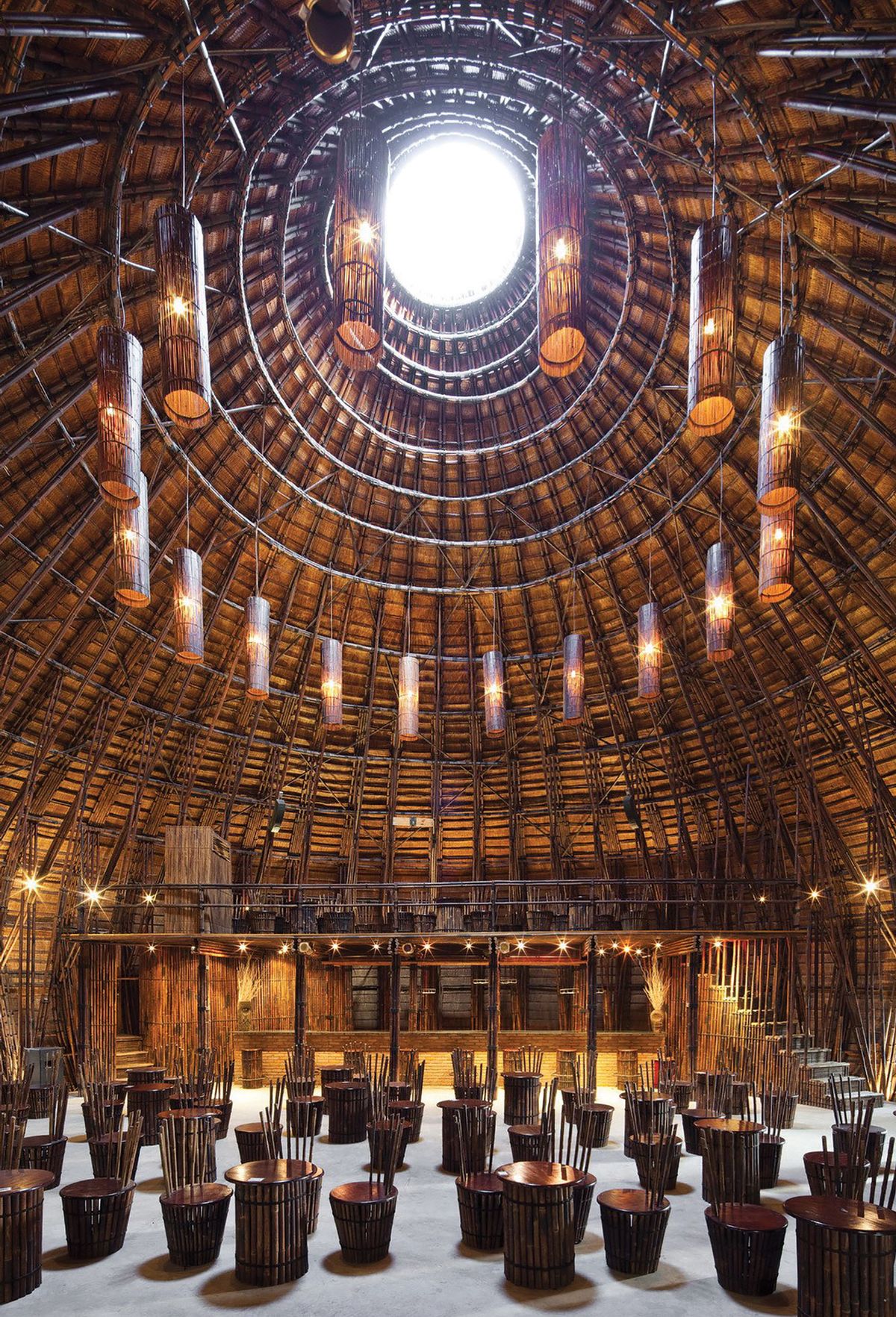

Complex and intricate bamboo structure of a restaurant designed by Vo Trong Nghia in Vietnam's Son La province. Photo: Hiroyuki Oko

The buildings discussed in the “Green” volume are made of concrete and brick; Vo’s practice has researched techniques such as cavity walling as a means to lower the carbon footprint of these materials. They have a porosity that derives partly from tropical typologies and traditions—easy, informal circulation, lots of natural ventilation, plenty of horizontals to protect against the sun and the rain, no real need to keep the cold out—but their severe, fragmented surfaces, offering glimpses into shady internal spaces, enriched by textural effects here and there (I liked the bamboo formwork in the House for Trees, a residential compound in Ho Chi Minh City) and punctuated by “sky gardens” and other ebullient outbreaks of vegetation, have a rhetorical force that goes beyond the vernacular. In keeping with the peri-apocalyptic flavour of so much ecological thinking, they seem to speak of a new society diffidently blossoming in the ruins of an old one (sometimes literally: the Atlas Hotel in Hoi An looks like a Louis Kahn building that’s been reclaimed by tropical rainforest).

Material possibilities

The works in “Bamboo” seem mostly to have been done for clients in the hospitality and tourist industries, but they have a serene dignity that belies their worldly role. Bamboo is deeply embedded in many Asian cultures, both as a building material—it’s flexible, strong, light, cheap and, avant la lettre, quintessentially sustainable—and a feature of the natural landscape. Traditional Chinese architecture contains references to bamboo construction, retained in later masonry and terracotta forms, in the same way as it is assumed the architectural language of the ancient Mediterranean contains a petrified echo of earlier timber structures. Bamboo is still extensively used for scaffolding in parts of Asia. Yet it’s the Colombian Simón Vélez whom Vo credits with awakening his interest in the possibilities of the material.

In Vo’s hands bamboo achieves wonderful effects: bundled into laminates, plaited into vaulting, lashed into lattices. The light, open structures illustrated here have a paradoxical monumentality, shaping resonant and almost ceremonial spaces while sitting harmoniously in their often stupefyingly beautiful surroundings. Indeed a feeling for context is one of Vo’s many strengths: a pentagonal villa in Ha Long seems to speak to the famous sugar-loaf crags that line the bay; the “Bamboo Stalactite”, a temporary structure created for the 2018 Venice Biennale, suggests a row of fishing nets drying in the sun.

• Vo Trong Nghia, introduction by Philip Jodidio, Vo Trong Nghia: Building Nature, Thames & Hudson, 2 vols, 400pp, 393 colour illustrations, £50/$75 (pb), published UK 27 January 2022, US 19 April 2022

• Keith Miller is an editor at The Telegraph and a regular contributor to the Literary Review and the Times Literary Supplement