I have often extolled the virtues of politically engaged art and exhibitions. But as I look ahead to exhibition programmes in 2022, the show I’m most fervently anticipating offers a respite from global events and promises much formal beauty, balance, colour and harmony: the delayed Raphael show at London’s National Gallery.

The perception of Raphael only as a purveyor of gentle beauty is something of a cliché, of course, perhaps most famously expressed by Kenneth Clark in his documentary series Civilisation, when he described him as “the supreme harmoniser”, which meant that he was “out of favour today”—which was 1969, of course. The idea was that harmony and balance were out of step with the fractured realities of the modern age, whereas the polymathic, cerebral genius of Leonardo and the rupture and dynamism of Michelangelo imbued their work with perennial modernity.

The Raphael Court at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London

Especially after the 500th anniversary celebrations of 2020, you’d never argue Raphael was unpopular, but he doesn’t have the same cut-through with a wide public as the other members of that High Renaissance trinity. He also represented more than calm radiance, of course—take the strangely crestfallen Pope Julius II in the National Gallery, Raphael’s appointment as architect of St Peter’s, and the fact that, apparently, he created the first plumbed loo for the papal apartments. Above all, look at the cartoons in their newly refurbished gallery at the Victoria and Albert Museum or the Stanze, the great frescoed rooms in the Vatican, which the National promises to present using new technologies in its show.

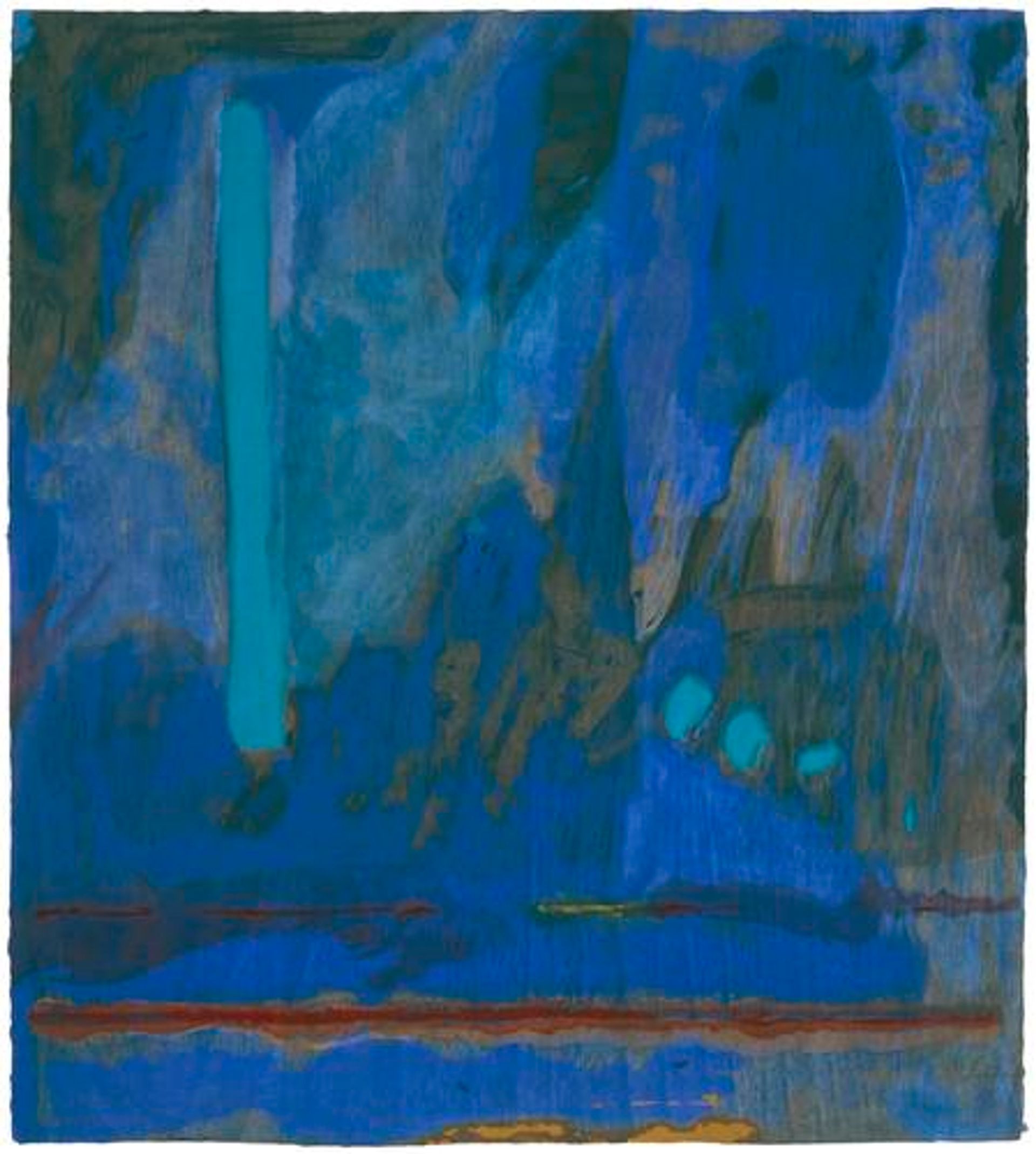

Yet, Raphael’s sublime harmony is an underrated quality. I was reminded of this in one of 2021’s great exhibitions: Helen Frankenthaler’s woodcuts at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London. There, we followed Frankenthaler’s prints from a painted prototype that would then be used by master printers like Kenneth Tyler and Yasuyuki Shibata to produce a print in dozens of colours and from multiple woodblocks, leading in some cases to more than 50 trials before Frankenthaler’s final artist proof. The seven prints that form Tales of Genji took more than three years to complete.

Helen Frankenthaler's Tales of Genji III (1998)

And yet, as Frankenthaler intended, they appear effortless, as if done “at once”. And that immediacy connects with an avowed attempt to make art that was beautiful: “A picture that is beautiful, or that comes off, or that works, looks as if it was all made at one stroke,” she said. But tellingly, in Frankenthaler’s notes on one of the test prints in the show, she points out its qualities in comparison to other tests and urges her collaborators to replicate the effect but adds: “NO schmaltz pliz!”

Frankenthaler once toldThe Art Newspaper that “there was an attempt in certain artists’ circles” in the modern era “to tear down the words ‘beauty’ and ‘beautiful’”. One of her heroes, the 20th century’s great harmoniser, Henri Matisse, faced similarly minded detractors. He spent a lifetime following his conviction that the artist should “express a vision of colour, the harmony of which corresponds to his feeling”. Read Hilary Spurling’s Matisse biography and you learn that the beauty and harmony he sought was hard won and balanced on a knife edge, just like Frankenthaler’s. As we’ll see in the National’s Raphael show, to dare to achieve harmony, in whatever age—and with NO schmaltz, pliz!—is a supreme achievement.