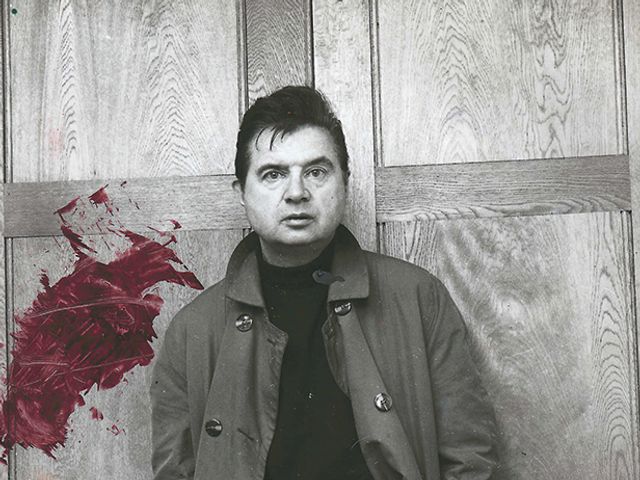

“Francis was very aware of animals and how animal we humans are. We might put on suits, but the animal instinct is still very strong. It’s still fear, lust and rage.” This, says Michael Peppiatt, is the guiding principle behind Francis Bacon: Man and Beast, the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) exhibition he has jointly curated with the institution’s Sarah Lea.

Peppiatt—biographer and confidant of Bacon—has arguably been the foremost promoter of the artist’s work since his death in 1992. “I know he was interested in animal instinct, and animal instinct in human beings as well. When I went through the oeuvre, I realised this was a whole facet of Bacon’s interest and imagination, and it hadn’t really been explored before,” Peppiatt says.

Bacon called bullfighting

‘a marvellous aperitif to sex’

The exhibition will bring together paintings containing actual images of animals, such as Bacon’s 1969 bullfight series, with more emblematic figures of variously distorted and tormented humans, including the “screaming pope” Head VI (1949), as well as the bizarre, hybrid creatures contained in both his early crucifixion paintings and his 1980s work inspired by classical Greek tragedy.

Peppiatt, who got to know Bacon in the early 1960s, remained a close friend throughout his life. He says that his own theory is that Bacon, while rigorously pursuing the urban and decadent lifestyle for which he became notorious, was in fact responding to a wild, rural childhood (as the son of a former army officer who had relocated to Ireland to train racehorses), which he professed to despise in later life.

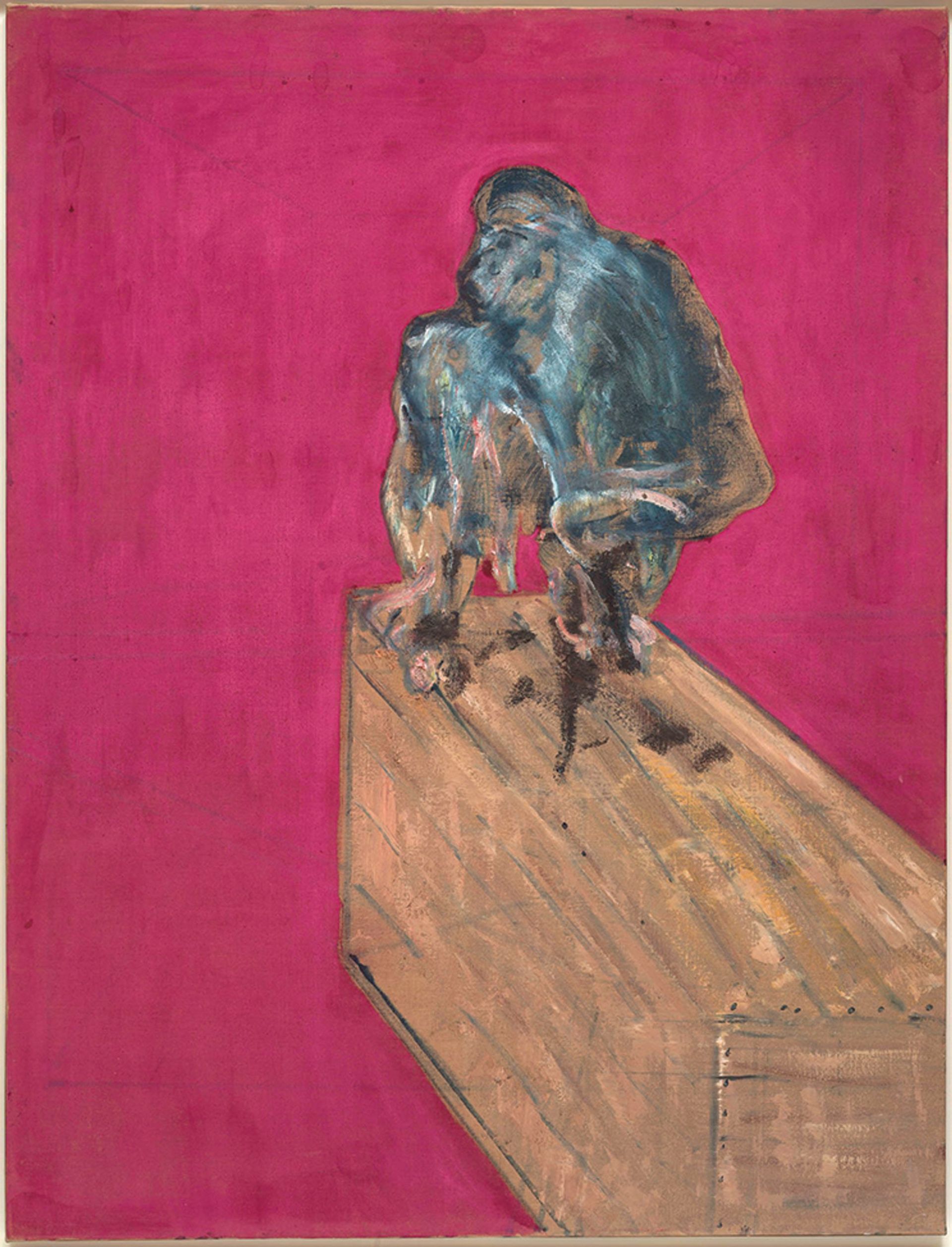

Bacon’s Study for Chimpanzee, which he painted in 1957. Animals, and animal-like figures, were a regular theme in his work Photo: David Heald © Estate of Francis Bacon and Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation; DACS 2021

“He turned against the circumstances of his childhood and dismissed it all as absurd, but he wasn’t born in a bar in Soho, he was born in the wilds of Ireland, surrounded by nature,” Peppiatt says. “Animals and animal behaviour was what he did, even if he was allergic to both horses and dogs. This is my conjecture, but I think he got to know how animals reacted, how they rear or snort, and he would see life through the spectrum of animals and their behaviour.”

Peppiatt says the exhibition was lucky to get all of Bacon’s bullfighting pictures (including his final painting, from 1991), which he describes in the exhibition catalogue as “among the most direct and powerful encounters between man and beast in his work”. Peppiatt is, of course, aware of contemporary disapproval of blood sports, but says Bacon “was deeply moved by the whole spectacle”.

“I think it excited him: the danger, the blood, the courage. He also called bullfighting ‘a marvellous aperitif to sex’.” Equally crucial, according to Peppiatt, is that the bullfighting iconography meant Bacon could directly measure himself with the artist who—above all—intimidated him: Pablo Picasso. “He was obsessed with Picasso,” Peppiatt says. “He once said to me, out of the blue, ‘I have to be aware of Picasso the whole time, there’s no way round it.’” The two artists never met, though. “Bacon didn’t want to, and I can see why,” Peppiatt says. “You suddenly get these two heavyweights in the ring—what’s going to happen?”

• Francis Bacon: Man and Beast, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 29 January-17 April