As the fifth anniversary of the invasion of Afghanistan approached, George W. Bush announced that “America has no interest in being the world's jailer”. Fifteen years later, the detention camp created at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base remains open and has become a millstone for successive administrations intent on closing it. The centrality of this prison, which opened 20 years ago this month, in the events of the last two decades has resulted in a steady flow of people traveling to it, to participate in or report on trials, or in some cases to focus on conditions at the prison itself. These have included many photographers, some of whom produced largely illustrative press photographs, others seeking to make a statement about the camp and what it represents.

The British photographer Edmund Clark has focused on the prison in three of his projects, including his 2010 book Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out, which examined the long-term impact of incarceration. “I was making work in a prison when the detention camps at Guantanamo became global news,” he says. “I could see how these experiences of incarceration represented how America and its allies were responding to the 9/11 attacks.” Clark began photographing the homes of British former Guantanamo prisoners following their release back to the UK, juxtaposing these images with photographs of the prison.

Debi Cornwall, Downtown Lyceum (2014), from Welcome to Camp America: Inside Guantánamo Bay (Radius Books, 2017) © Debi Cornwall 2014

As an American, events at Guantanamo felt close to home for Debi Cornwall, and the domestic and recreational aspects of the base as a residence for both servicemen and prisoners became a key part of her book Welcome to Camp America, published in 2017. “As a citizen, I felt a responsibility to look,” she says. “And as someone who had devoted a 12-year legal career to representing victims of government abuses, the existence of a prison interning Muslim men for years, without charge or trial, at a site specifically chosen to exist beyond the reach of the law, was of personal interest to me.”

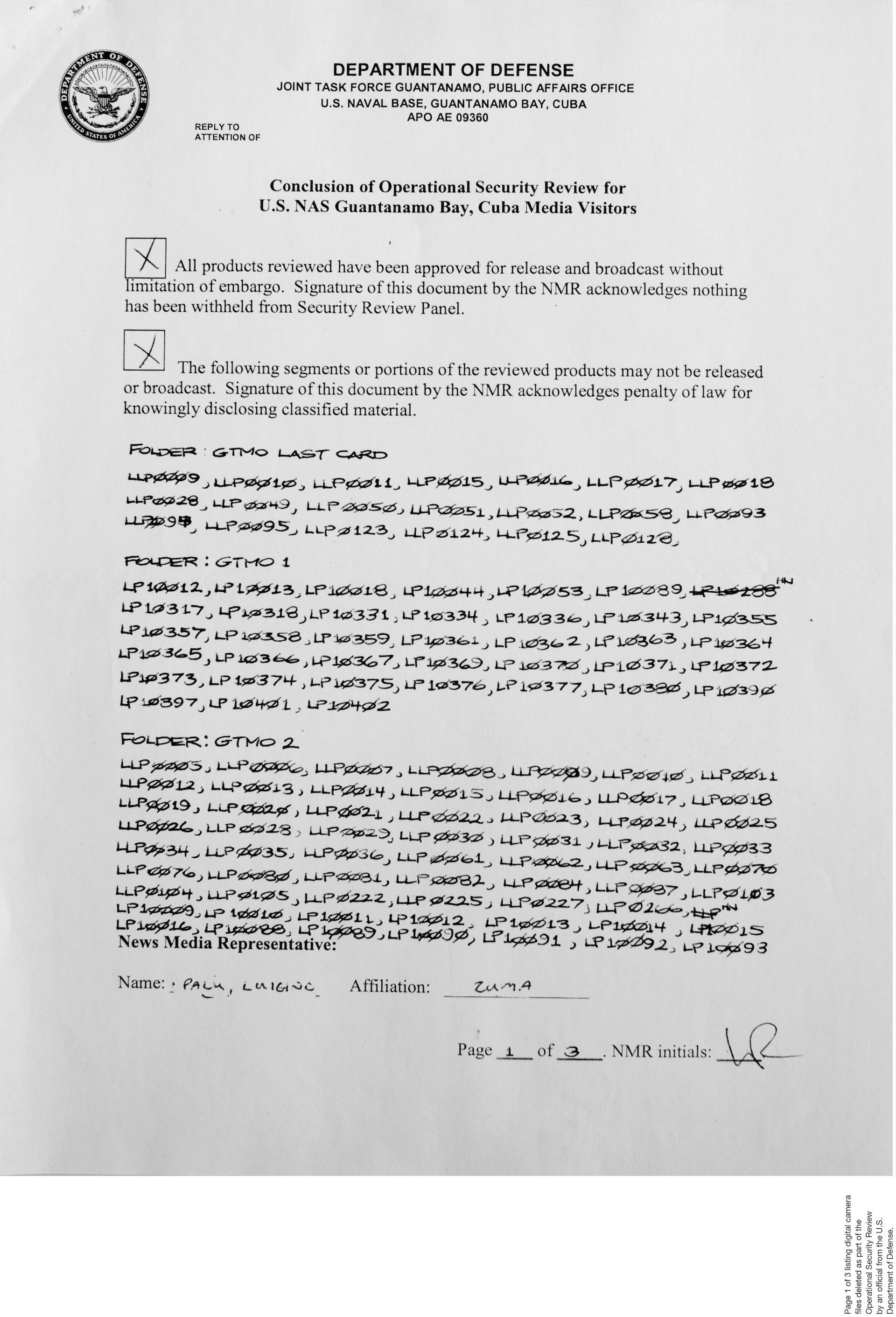

The Canadian photographer Louie Palu took yet another approach, seeing the camp as an opportunity to educate viewers on visual literacy and key American values in his 2014 publication Guantanamo: Operational Security Review. For Palu the prison was “a symbol of torture that remains as a legacy to a new form of global war most of which is secret and hidden from view”.

Louie Palu, Detainees praying in Camp 4 at the detention facility in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba © Louie Palu

Reflecting the opacity of this new war, photographing Guantanamo presented significant challenges to all three. Although press tours were conducted at the prison, these were stage managed and came with strict conditions attached, necessitating creative responses. For each of the three, avoiding some of the visual clichés of the camp was an important objective.

“Having spent time with ex-detainees and listened to them talk about their experiences I knew they were still, in some ways, living in or with those spaces and their feelings of responsibility for the detainees they knew who were still there,” Clark says. He decided he “did not wish to repeat the image tropes of anonymous, dehumanised detainees and guards that I had seen in much of the news photography of Guantanamo.” Instead he focused on the spaces and objects in the prison, using a medium format digital camera instead of the typical cameras used by press photographers.

Edmund Clark, Home (2010) Courtesy the artist and Flowers Gallery

Palu echoes these concerns, explaining that “I had to look further than literal news photography and realised that [what] I photographed and later published in Guantanamo: Operational Security Review is not about the prison, but about the history of war and what we do and most importantly what we don’t see.”Reflecting this, his publication includes lists of the images he had to delete as part of the censorship process required in order to photograph there.

Spread sample of redacted photographs from Louie Palu's publication Operational Security Review © Louie Palu

Cornwall was pragmatic about what she would encounter at the prison. “I knew I would never be shown what happened behind closed doors,” she says. “Instead, I opted to lean in and look at what I was being asked to see.” A chance comment helped fix her approach. “Soon after I arrived, my military escort declared, ‘Gitmo is the best posting a soldier could have. There’s so much fun to be had here!’ I decided to look at the ‘fun’ show—and add context later.”

Part of that context came in the form of subsequent related work, including photographs of 14 former prisoners, an element of the project that was also a direct response to prohibitions on showing the faces of current prisoners. These different elements coalesce in exhibitions of her work, like as the one currently taking place at Stadthaus Ulm in Germany.

Debi Cornwall, Sami, Sudanese (Qatar), Al Jazeera Cameraman, Held: 5 years, 4 months, 16 days, Released: April 30, 2008, Charges: never filed (2015), from the book Welcome to Camp America: Inside Guantánamo Bay (Radius Books, 2017) © Debi Cornwall 2015

The events of the last 20 years have been so intensively depicted in visual media, what did the photographers hope their photographs would add? Palu’s answer perhaps reflects his background as a journalist, as he argues it is in part a matter of a record, and accountability. “As problematic as the overall history of photography is in terms of misrepresentation,” he says, “I do believe that creating a record and also even attempting some oversight or pressing for government accountability is our duty as artists, thinkers and photojournalists.”

Clark suggests the way he uses photography has the potential to counter-balance stereotypical tropes about the ‘enemy’. “I was seeking to create a representation that questioned the prevailing narratives about Guantanamo and the war on terror,” he says. “That focused on ideas of personal living space and domesticity to undermine messages of difference, otherness and racism implicit in much of the media coverage and government presentations.”

For Cornwall the importance of photography was a little different again. “Photography accesses different circuitry than words do,” she says. “Images can have an impact even before you know what you’re looking at. The visceral impact of a photograph, series or a photobook, can raise new questions, suggest common ground and start a new kind of conversation.” With the prison at Guantanamo Bay still a source of unresolved controversy and, as of this writing, holding 39 detainees, these conversations remain necessary and ongoing.