As the world mourns the death of revered actor and activist Sidney Poitier, Patron Gallery in Chicago is inviting visitors to honour his life’s work and legacy through a series of portraits by artist Greg Breda that celebrate Black cinema.

In Still, Breda presents 7 paintings that depict scenes from movies spanning 5 decades of Black film. The artist avoided blockbusters and opted for examples of a slow burn cinema he describes as “quiet films” that were overlooked by viewers and critics. More broadly, Still is about the cinematic moments that leave indelible marks on our memory. “Film gives vision for a lot of folks,” the artist says, “it reflects our lives and guides our lives all at the same time.”

There are few layers to the show’s title. While Still refers to images of frozen moments in film and the meditative state of stillness, it’s also a commentary on social history. The issues Breda depicts are enduring and ever-relevant: gentrification, displacement and racism run parallel with universal themes of love, loss, empathy and freedom. While the films show characters navigating these issues, Breda isolates them in a single frame. “I was looking for these moments that I could excavate, like these narratives or these stories or allegories that I could lift up out of them,” he says.

In film, an arc is the byproduct of a series of formative events that changes a character for better or worse. Their growth, or in some cases their regression, becomes an emotional journey that sets the stage for their metamorphosis. Breda’s paintings mirror this trajectory on canvas. His portraits generally involve a lone subject in the kind of deep concentration that captures the spark of an epiphany or the lonely pangs of regret. This introspection is found in subtle details: a downward gaze, a hand cradling the chin or an open page of a journal. The compositions include other symbolic details in the subjects’ surroundings such as floral arrangements, upholstery, architectural details or light sources. The paintings tell stories, which become all the more vivid when experiencing the films on which they are based.

Greg Breda, Miss Sepia 1957 (2021) Courtesy the artist and Patron Gallery, Chicago

In Miss Sepia 1957 (2021), Breda captures actress Diana Sands in a scene from the movie The Landlord where Sands’s character, who is pregnant, is lamenting the loss of her former life while she contemplates an important decision that will impact her unborn baby. Her presence standing in front of a window while facing away from it becomes a visual metaphor for missed opportunity.

While interiority and contemplative solitude dominate the thematic structure of Still, some paintings depict assured confidence, as in This is where it’s at (2021), which features a sporty Black man donning a white motorcycle helmet, goggles, and a sleek black leather jumpsuit as he confidently surveys the landscape in front of him. The portrait is of Poitier’s affluent, widowed character Dr. Matt Younger in the 1973 romantic drama A Warm December. This painting differs from the more introverted, self-reflective moments Breda tends to depict in his work.

“Sidney’s character is living the life,” the artist says. “He goes back and forth to Europe, he has money. He has freedom. ‘This is where it’s at’: the pinnacle of freedom.” Poitier’s characters wore invisible armors of strength while projecting a quiet confidence that afforded them the privilege to navigate unfamiliar and hostile terrain. In 2012 the writer Daniel Garrett wrote, “The inner life is the most neglected, most significant, most mysterious thing in the world, and Sidney Poitier gave us portraits of an enlightened spirit, of human freedom.” Breda’s portraits respect the same vision of interiority and freedom.

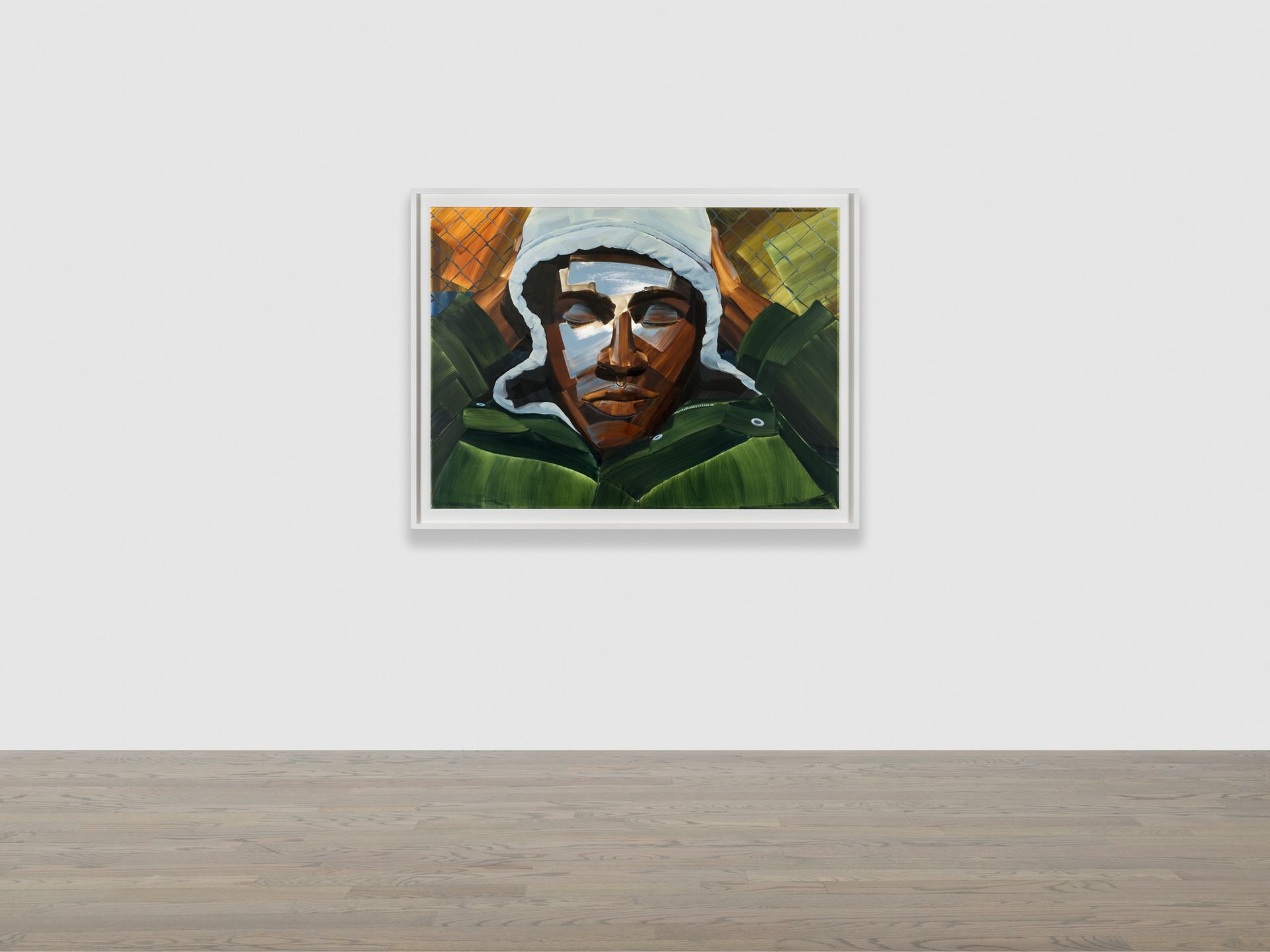

Installation view featuring You’ll be ok (2021) by Greg Breda Courtesy the artist and Patron Gallery, Chicago

Two of the six films that inspired the paintings in Still star Poitier, the other being Brother John, a 1971 movie about a mysterious man who returns to his hometown. As questions about his life percolate in the community, we learn he has an uncanny attachment to death. Whether that connection is significant or happenstance is unknown. Poitier’s character seemingly blows into and out of town leaving more questions than answers in his wake. In When the Wind Comes Again (2021), Breda paints Poitier standing on a hillside gazing skyward while holding a monarch butterfly in his hand. The otherwise bucolic setting is undercut by the billowing smokestacks in the distance. Both the film and the painting explore freedom, liberation and capitalism, placing Poitier in the centre of conflict while he maintains the ability to rise above it.

Through portraits that encourage slow looking, Breda encourages viewers to experience a uniquely curated selection of movies. “My hope is that people do take a moment to look back on these films,” he says. “It’s just people living their lives and it’s important to view that.”

Through these moments Breda offers viewers a window into characters’ transformations, crystallizing the moment between who they were and who they are about to become. These are portraits of freedom. He adds: “Those are the stories that I think Black America is demanding that people tell.”

- Greg Breda: Still at Patron Gallery, Chicago, Illinois, until February 26