Wayne Thiebaud, the California-based painter known for his supple depictions of America’s mid-century visual lexicon, be it through cityspaces, diner windows, or rows of pies and cakes—in which the paint itself was often as thick and rich as fondant icing—died on Christmas day at his home in Sacramento. He was 101 years old.

Born in 1920 in Mesa, Arizona, Thiebaud moved with his family to Long Beach, California when he was just a baby. When the Depression unfolded across the US, his family moved to his maternal uncle’s ranch in Utah—Thiebaud’s grandmother was one of the state’s original 19th-century Mormon settlers—where they spent a few years before returning to Southern California. His uncle Jess was an amateur cartoonist and Thiebaud later attributed the time he spent in Utah watching Jess draw, which was sandwiched between fulfilling farm duties, for igniting his interest in art. As a teenager back in Long Beach, Thiebaud studied commercial art and found work as a sign painter. At age 16, he landed an apprenticeship at Disney’s animation studios, a job which, according to the New York Times, he was given partly due to his ability to draw Popeye with both hands at the same time.

During the Second World War, Thiebaud served in the Air Force from 1942 to 1945, where his artistic ability kept him away from combat. He first worked as a cartoonist and artist in the Special Services Department before being transferred to the First Motion Picture Unit, a branch of the Air Force created to make military films, many of which were used for training purposes, and where Thiebaud’s commanding officer was future president Ronald Reagan. Throughout the war, he also worked as illustrator for the Air Corps newspaper.

Between 1946 and 1948, Thiebaud worked as an illustrator for the Rexall Drug Company in Los Angeles before moving to Northern California—where he would live for the rest of his life—and returning to school on the GI Bill, earning bachelors and masters degrees in fine art from California State University, Sacramento. Thiebaud began teaching while still a graduate student, first at Sacramento Junior College before joining the faculty of University of California, Davis, where he would continue to teach for over 40 years. (In the mid-60s, a young graduate student named Bruce Nauman served as Thiebaud’s teaching assistant.)

Wayne Thiebaud, Three Cones (1964), private collection, courtesy Acquavella Galleries Art © Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

In 1962, gallerist Allan Stone held Theibaud’s first New York solo-show, a sold-out success from which the Museum of Modern Art bought a painting for its collection. “He came to New York in 1961 to look for a gallery. He started on 56th Street and he walked up Madison Avenue and was turned down by every single gallery he went to,” Stone told CBS Sunday Morning in a conversation on the occasion of Thiebaud’s 2001 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of Art. At the time, Stone’s gallery was on 86th Street, 30 blocks from where the painter’s walk had begun. “[Thiebaud] was just there leaning against the doorway and I hollered out, ‘Can I help you?’ He said, ‘No, I just want to rest here.’ I said, ‘What are those things under your arms?’ and he said, ‘These are just rolls of paintings, but you wouldn't be interested in them, nobody else is.’”

Stone convinced the fatigued and distraught Thiebaud to show him the work—pictures of rows of pies and slices of cake—and a show was arranged for the following year. (Stone, who died in 2006, would go on to host nearly 30 more solo shows of Thiebaud’s work.) Also in 1962, Thiebaud would have his first museum exhibition, a show at San Francisco’s de Young Museum, as well as inclusion in a pivotal group exhibition in New York organised by Sidney Janis, where his work was shown alongside Andy Warhol, Roy Liechtenstein, Robert Indiana and others.

His subject matter, along with the era in which he rose to prominence, often resulted in Thiebaud being categorised as a Pop artist, an allocation he never embraced. While undeniably focused on quotidian imagery, the bread and butter of Pop, it was not the same conceptual framework that drew individuals like Warhol and James Rosenquist to Brillo Boxes and lipstick that pulled Thiebaud towards meringue pie and gumball machines. It was foremost the formal elements of such treats that made them appealing to the painter: “If you really look at a lemon meringue pie or a beautiful cake, it’s kind of a work of art, and that’s what attracted me,” he told Artnet in an interview just last year, at age 100. “And when you put them in rows, you have the ability to orchestrate them, to imbue them with what you hope is some extra interesting looking forms.” As the decades passed, the works never lost their ebullient joy, though they gained a nostalgic and at times surreal sense of melancholy that only heightened their magic.

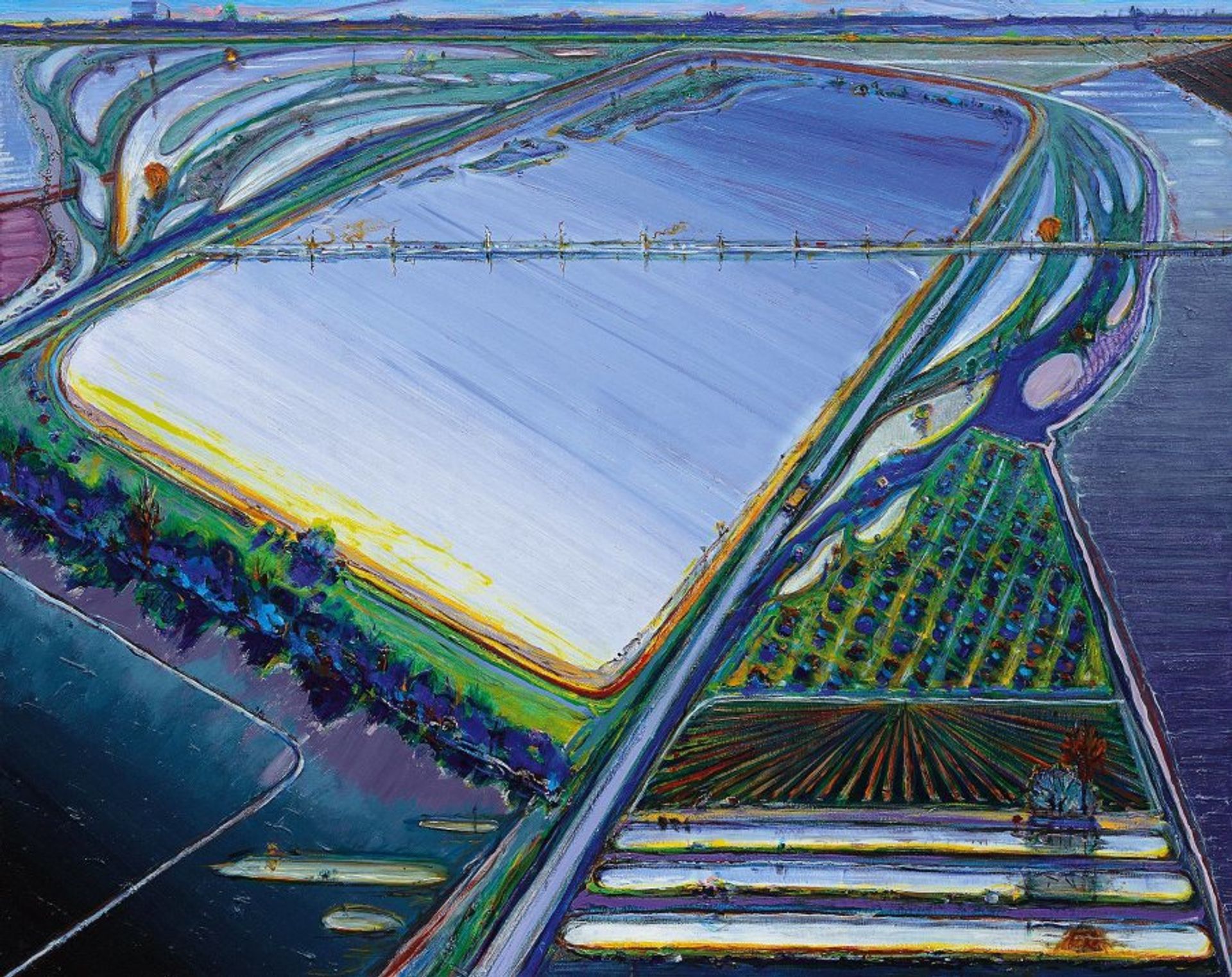

Wayne Thiebaud, Flood Waters (2006/2013), Private Collection, Courtesy Acquavella Galleries Art © Wayne Thiebaud / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Partly to avoid being pigeonholed, Thiebaud began expanding the imagery of his paintings soon after his initial success. Though he never stopped painting rows of desserts, he developed expansive, decades-long bodies of work on a number of other subjects, including the dizzying hills of San Francisco, portraits of loved ones, clowns, the California landscape and a series of mountains, some of which the artist painted and showed as recently as 2019 at Acquavella Gallery. The work, regardless of subject matter, nearly always maintained the lush, icing-thick paint application the artist first mastered when mimicking cakes and pies.

Up until his death at 101, Thiebaud continued to paint nearly everyday, playing tennis two to three times a week (the 2020 Artnet interview cited earlier ended with Thiebaud leaving for a match), and expanding the purview of his work ever further. When asked on CBS Sunday Morning how he’d like viewers to react to his paintings, the artist said: “I’d like for them to laugh a little. If we don’t have a sense of humour, we lack a sense of perspective.”