Drive north from Oslo for seven hours and you will arrive in Trondheim: Norway’s third largest city and its most populous urban area within reach of the Arctic Circle. Here, at a latitude similar to that of Reykjavik, Iceland, lies the country’s biggest university, a burgeoning restaurant scene and, as of last month, its largest commercial art gallery.

At first glance, the trading element of the Kjøpmannsgata Ung Kunst (KUK) is not so apparent. Spread across two floors with a restaurant and gift shop, this multi-purpose space—described on its website as an “art house” dedicated to emerging art—could almost be categorised as a kunsthalle, except that its not-for-profit business model is reliant on the sale of exhibited works.

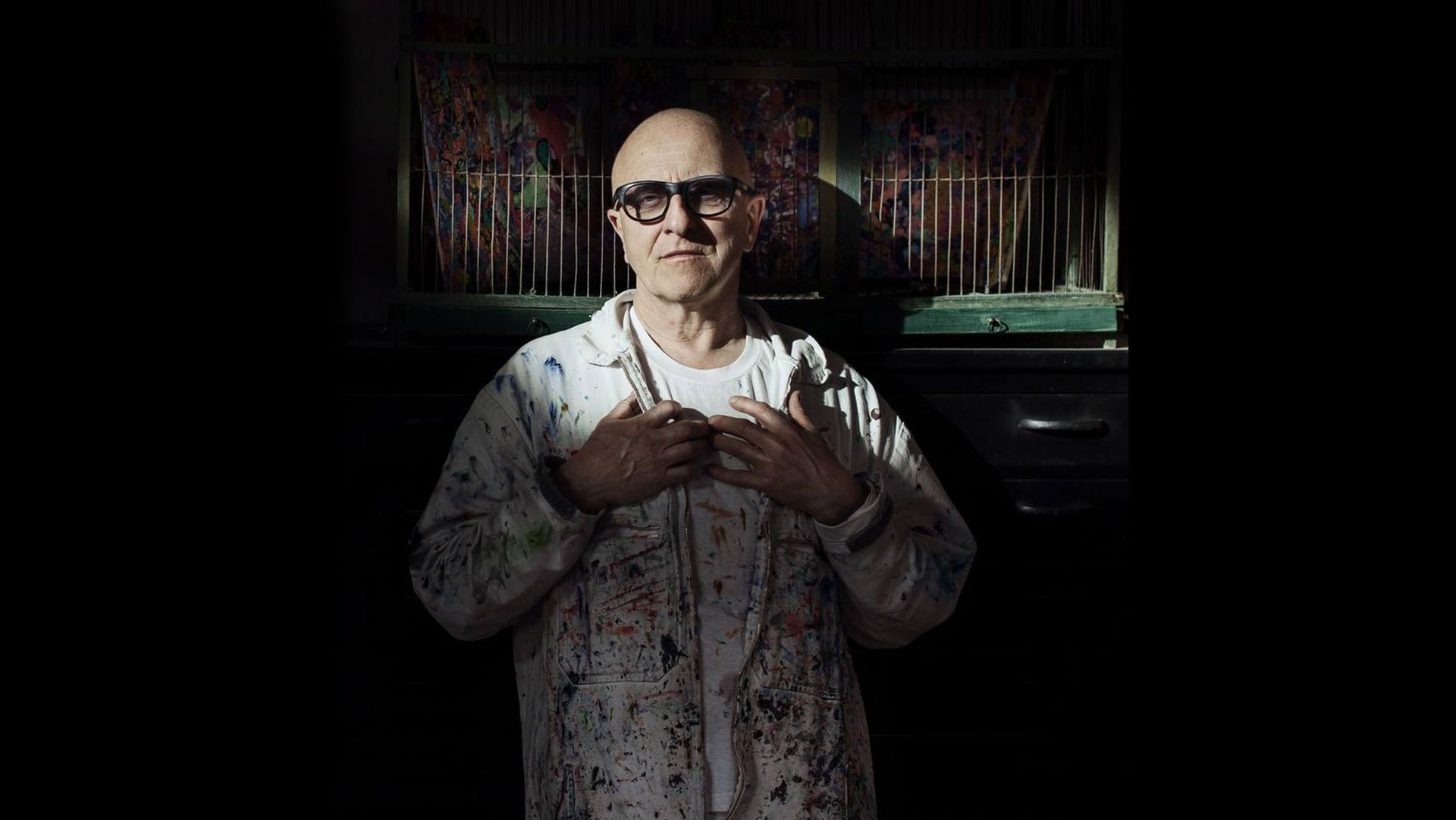

Kjell Erik Killi Olsen, founder of KUK Trondheim. Courtesy of KUK Trondheim

The gallery’s construction has been funded entirely by its founder, the Trondheim-born painter and sculptor Kjell Erik Killi Olsen, who owes his status as one of Norway’s wealthiest artists to his family’s wholesale goods business. It was the burden of this legacy that drove Killi Olsen to New York in his 20s to pursue art, he says, likening his inheritance to “a noose” around his neck. But now he wants to give back to his hometown: “When I began making my art in the 1970s, local children were not allowed to see it. But Trondheim, conservative as it still is, has changed since then and I want to show its young artists that they can create cutting-edge, provocative work here and have it be appreciated,” he says.

Elizabeth Ravn's painting of her partner installated in It's Just a Phase at KUK Trondheim. Courtesy of KUK Trondheim

True to form, the KUK's exterior is now emblazoned with an image of a woman during childbirth with her crowning newborn, by the German photographer Heji Shin, who is one of 31 artists taking part in the inaugural show. Organised by the Scandinavian artists Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset (better known together as the duo Elmgreen & Dragset), and the Danish curator Rhea Dahl, It's Just a Phase (until 13 February), brings together new and recent works that respond to life stages such as birth, death, ageing and coming out.

Spread across eight galleries, many of the artists on show are yet to receive a solo institutional exhibition, and some have no commercial representation. These include the Berlin-based painter Elizabeth Ravn, who shows intimate interior scenes composed from broad brushtrokes, and the British artist Nikhil Vettukattil, whose moving image installation fills the gallery's basement level with the thumping sounds of hardcore techno music.

For the inaugural show, the KUK has provided each of the participating artists with an undisclosed exhibiting fee, completely separate to the sales made, for which it takes a 40% commission. It also provides production fees for specially commissioned works such as an installation by the Egyptian-born Mahmoud Khaled, who has converted a basement gallery into a white carpeted den with a 1960s, Hugh Hefner-style leather bed.

“Norway is very different to other Western European countries, there is still a huge gap between commercial and institutional funding, which typically makes it harder for younger artists to show work,” says Dahl. “What is most important is that this space is involved in all stages of an artwork. An artist needs support well before they are ready to exhibit their work—that is only the tip of the iceberg, even if it’s all the public sees.”

A gallery converted from a former auto shop at the KUK Trondheim. Courtesy of KUK Trondheim

“When I was a kid we didn’t even have an art museum here," says Dragset, who grew up near the city. "For Trondheim to now have a space where artists can sell experimental work is indicative of how much it’s evolving.” This local swell of interest in contemporary art is one that precedes the KUK's arrival; as Dragset points out an actual kunstalle dedicated to contemporary art opened in Trondheim in 2016. However, while the kunsthalle tends to stage exhibitions by more established names in the contemporary art world, the KUK focuses on “emerging and younger, experimental voices”, says its artistic director Cathrin Hovdal Vik. She adds that it is “complementary, not competing” to the ambitions of the kunsthalle.

To this end, it has established a partnership with the Trondheim Academy of Fine Arts, allowing its graduates to show in the space. Among the youngest artists in the inaugural show is a recent graduate of the academy, Samrridhi Kukreja, who practises under the alias Tuda Muda. Born and raised near Delhi, India, Kukreja relocated to Trondheim three years ago to study. Her work, located by the downstairs toilet, shows a video projection of the artist observing her body in a mirror. "Prior to the KUK I can't imagine where I could have sold a work like this in Norway without going to Oslo," she says.

Constantin Hartenstein's resin works refer to popular imagery from his childhood in the German Democratic Republic. Courtesy of KUK Trondheim

And while Trondheim still might not seem the most likely location for the art trade, a number of artists cut deals on the gallery's opening weekend, including the Berlin-based artist Constantin Hartenstein, who sold a blue resin wall-hanging work based on popular images from East Germany to a Trondheim-based collector.

The most prominent patron to have made a visit to the space, Queen Sonja of Norway, is yet to purchase a work from the show. However she did, according to Dahl, take particular interest in a peformance given by Agata Wara, which involved the artist ascending a set of stairs and leaving behind imprints of red paint. Afterwards, Wara discussed her work in the context of blushing, likening the involuntary bodily process to a “face boner”, to which the Queen replied: “I blush all the time”. Perhaps experimental art is not as bold a proposition here as one would imagine.