When US president Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the infamous Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, authorising the mass incarceration of residents and citizens of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast, renowned artist Chiura Obata (1885-1975) was a professor at the University of California Berkeley. Even so he, his family and thousands of others in the Bay Area and beyond were uprooted by the wave of anti-Japanese racism that swept the US following the attack on Pearl Harbor and eventually sent to the hastily constructed Topaz Relocation Center in the Utah desert near the town of Delta. Now, 35 works by Obata—including powerful, tranquil depictions of the ethereal landscape around Topaz he made while incarcerated there—have been acquired by the Utah Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA) in Salt Lake City.

The 35 drawings, prints and watercolour paintings have been gifted to the UMFA by Obata’s estate; the museum, which hosted the artist’s travelling retrospective in 2018, has purchased three additional works by the artist. As well as depictions of Topaz—in which the barracks-like buildings where around 8,000 people lived for more than three years are dwarfed by vast skies and the expansive desert—the works acquired include images of animals, flowers and California landscapes.

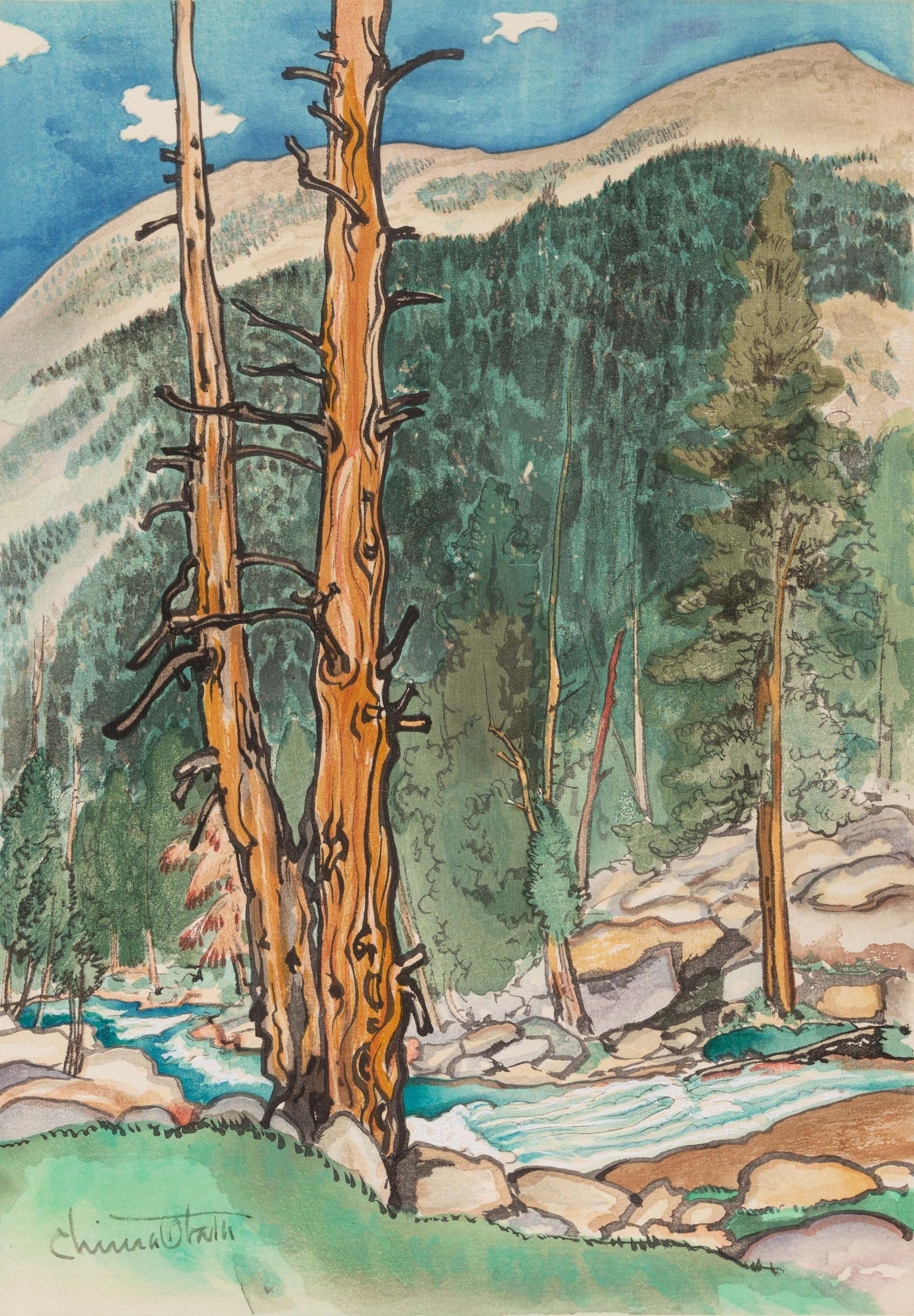

Chiura Obata, Upper Lyell Fork. Purchased with funds from The William H. and Wilma T. Gibson Endowment, from the Permanent Collection of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts Courtesy the estate of Chiura Obata and the Utah Museum of Fine Arts

“Obata never wavered from the inspiration he found in nature and his faith in the power of creativity. The solace that Obata found in the beauty of the Utah desert landscape was profound,” Kimi Hill, a member of the artist’s family, said in a statement. “Because many of these artworks were created in Utah, we hope people will be inspired to learn the history of wartime incarceration and go visit the actual camp site in Delta as well as the Topaz Museum.”

For Obata—who was already a prodigious artistic talent when he emigrated from Japan to the US as a teen in 1903—art proved a vital way of coping with displacement, dispossession and xenophobia. Before even arriving at Topaz, while being held at a former racetrack near San Francisco with 7,000 others, he founded an art school to teach fellow detainees. What eventually became the Topaz Art School counted some 600 students at its height, ranging in age from six to 70.

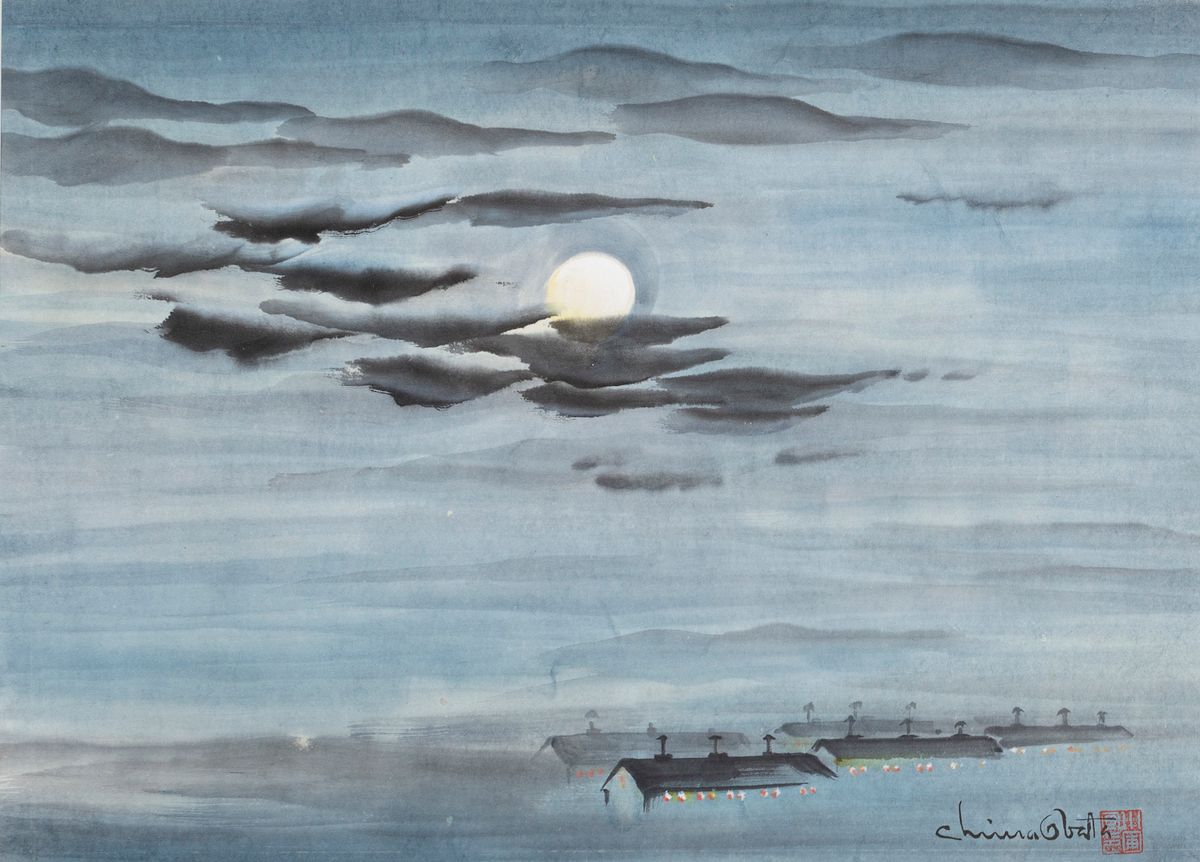

Chiura Obata, Very Warm Noon Without Any Wind. Dead Heat Covered All Camp Ground (1943). Gift of the Estate of Chiura Obata, from the Permanent Collection of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts Courtesy the estate of Chiura Obata and the Utah Museum of Fine Arts

The experience of the desert also changed Obata’s outlook on nature. “If I hadn’t gone to that kind of place I wouldn’t have realized the beauty that exists in that enormous bleakness,” he said in a 1965 interview.

Works from the acquisition will go on view in the UMFA’s permanent collection galleries in autumn 2022.

Obata’s depictions of and experiences at the Topaz Relocation Center were the subject of a recent episode of the Smithsonian Institution’s Sidedoor podcast.