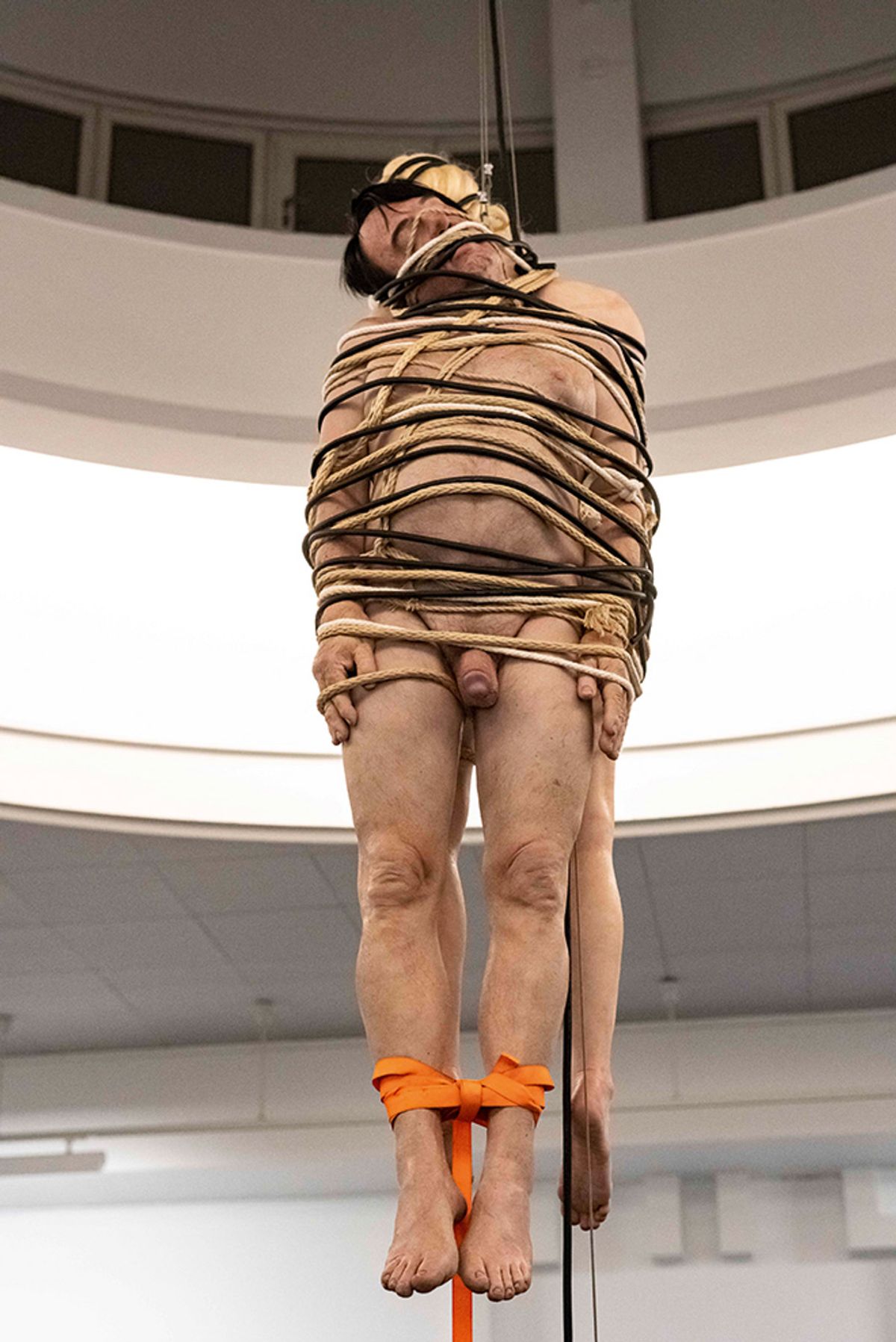

“Hitler was terrified of being publicly hanged, like Mussolini was. He instructed his guards to shoot him dead should the Third Reich fall,” a Norwegian curator tells me at the opening of the American artist Paul McCarthy’s new exhibition Dead End Hole at Kode Art Museums in Bergen (until 27 March). Nuggets like these add an unlikely sense of pathos to the sculpture looming above us: two highly realistic naked casts of McCarthy and his regular collaborator, the actress Lilith Stangenberg, costumed in wigs and moustaches to loosely resemble Hitler and his partner Eva Braun, hanging by cables from the gallery’s ceiling.

We were two of around 100 people that had gathered at the museum on a rainy November evening to witness a performance by McCarthy—his first in more than a decade. Expectations were high: his live works since the 1960s have involved him inserting a Barbie doll into his rectum and covering himself with mayonnaise and vomit. But with the American artist now 76, I wondered whether he still had the capacity to shock.

Paul McCarthy A&E, Adolf/Adam & Eva/Eve, (2021). © Paul McCarthy. Image courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Peder Lund

Frankly, yes. The main action took place in a former air raid bunker underneath the museum, where McCarthy and Stangenberg, fully dressed as Hitler and Braun, spent the better part of three hours churning through a sequence of increasingly depraved actions: the couple proceeded to strip off their clothes, drink heavily, brazenly snort what appears to be drugs, masturbate, hurl insults and urinate and defecate on each other. The action culminated with the pair naked, sobbing and clutching each other, before yelling “cut!”. All this was live-streamed to viewers in a gallery upstairs, who spoke in whispers conveying a keen mix of horror, fascination and embarrassment: “Did you see that? I can’t watch! Is it real? That surely can’t be real.”

The extent of the performance’s artifice was on everyone’s minds at a dinner later that night. Although one of Kode’s curators confirmed that the faeces and urine were synthetic, and the penis that McCarthy at one point injects with an unidentified substance is prosthetic—it raises the question, does it matter, when our sense of disgust is so palpable?

For decades, McCarthy’s work has willingly pointed to its own seams: camera crews and lighting rigs are often visible in his films, present only to emphasise our inability—and often unwillingness—to separate fiction from reality.

As a slightly reticent McCarthy told me the next day, the two characters of the work, titled A&E, can be viewed as stand-ins not just for the Führer and his wife, but also for Adam and Eve or “a tyrannical director and his muse”. Notably several times during the performance Stangenberg derides McCarthy for being a “bad artist”.

Paul McCarthy's DADDA (2017). Courtesy of the artist, Hauser &Wirth and Peter Lund

The blurring of reality and fiction is also present in the new, four-channel immersive film installation DADDA (2021) by McCarthy, in which actors playing Donald Trump and other famous Americans, including his wife Melania, Andy Warhol and Nancy Reagan, take a journey on a stagecoach, culminating in a bloody finale.

Is the artist drawing direct parallels between Hitler and Trump? “It’s not quite as simple as that,” he says, adding that his interest lies more in how casually comparisons are made between the two.

Nonetheless, it is this type of content that means McCarthy struggles to show his most controversial work in the US. For this reason, despite being represented by the mega gallery Hauser & Wirth, McCarthy says he is in “quite a lot of debt” from making this project, adding that he has recently been forced to sell a property to recover costs. His vast studio in Los Angeles, I am told later by one of his entourage, employs some of the film industry’s best cinematographers and technicians—not a cheap endeavour.

So why, after over 50 years, does McCarthy continue to plumb the darkest depths of human behaviour? What taboo is there left to break? "Provocation is only half of what I’m doing, I’m really trying to unravel something within myself, work things out,” he says. “And if the audience see something of themselves in that, then so be it.” Having witnessed the man in action, this process seems less akin to an unravelling than to an exorcism, but, as McCarthy points out, he is attempting to expel a demon that likely exists within us all.