Back in March, the UK's prime minister Boris Johnson wrote that Van Gogh’s Sunflowers lifted the soul. We certainly needed an uplift then—and there now seems to be just as much uncertainty in the air as when the year began.

Looking back on Van Gogh in 2021, Covid did little to slow down the slew of discoveries. Some tell us more about his art, others give us a deeper insight into his astonishing life.

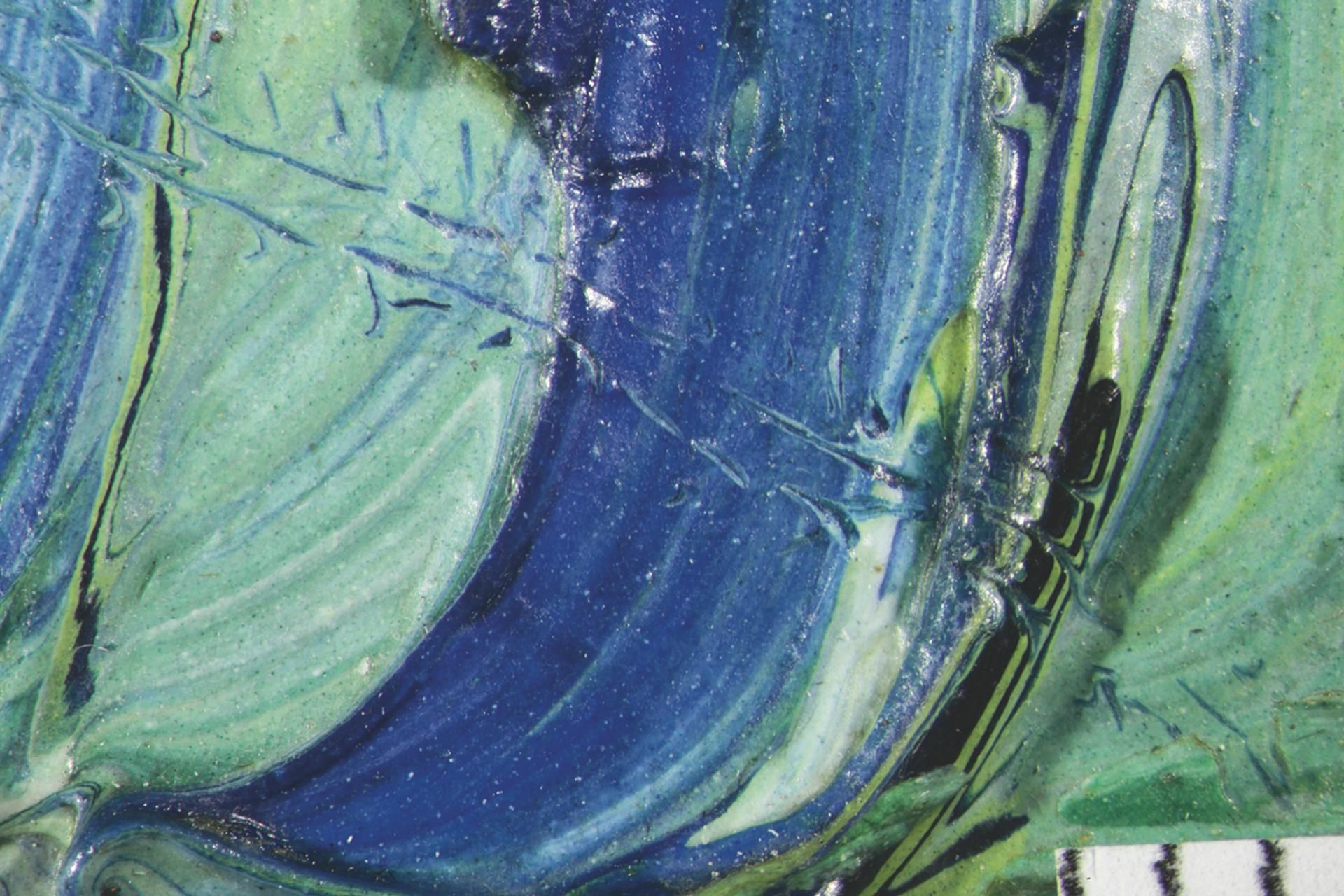

Traces of an insect walking through the paint, a detail from Van Gogh’s Olive Grove (July 1889) Courtesy of the Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo; photomicrograph: Margje Leeuwestein

One of the most exciting discoveries was finding the trail of an insect which had waded through Van Gogh’s thick impasto paint in his Olive Grove (July 1889). An 18cm track of tiny footprints was recorded by conservators at the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo. Evidence of the struggle of the terrified creature trying to escape confirms that the painting was begun outside among the olive trees, not inside Vincent’s studio.

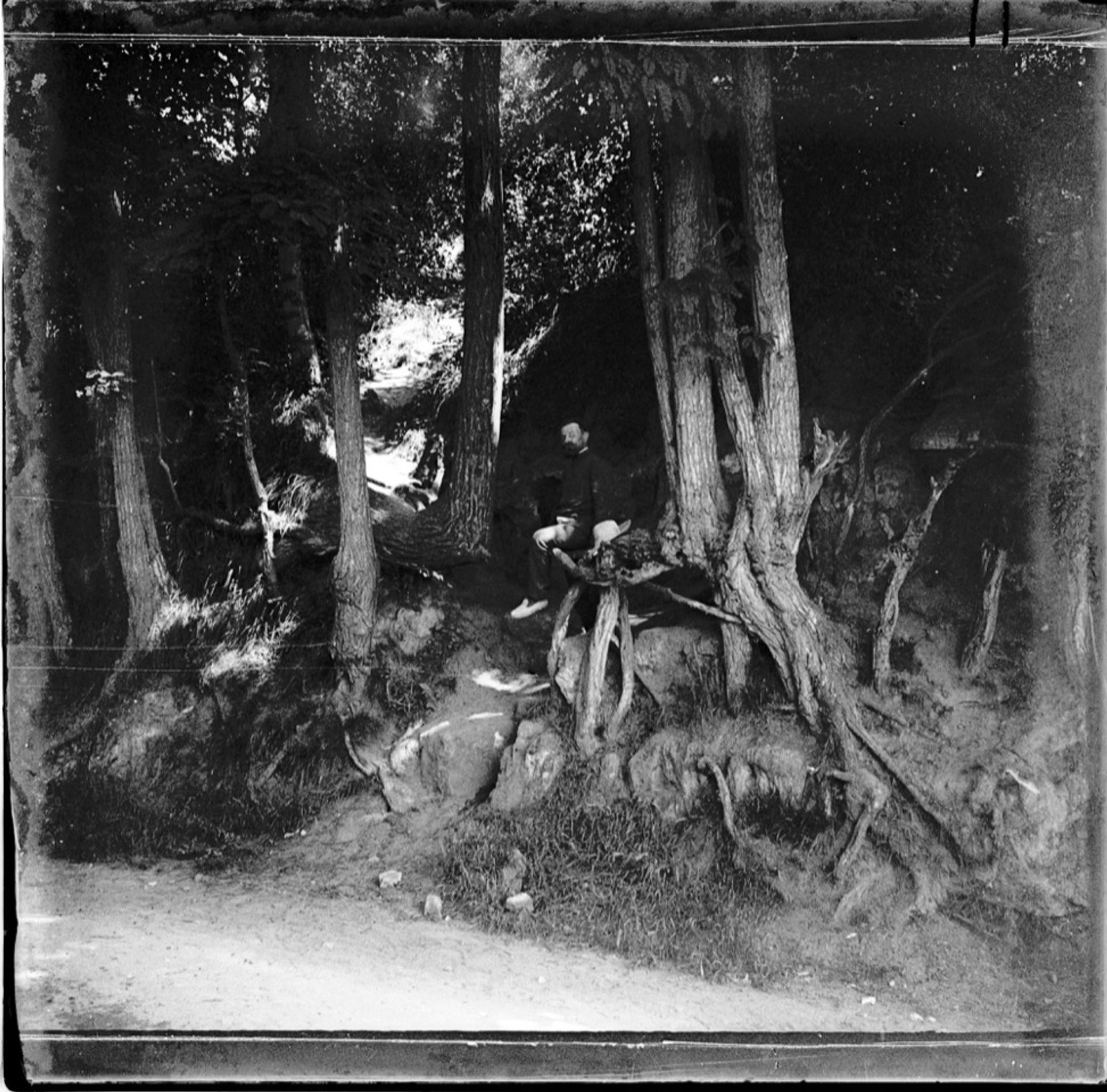

Trees at Auvers, July-August 1907, glass-plate negative (image illustrated here is reversed) Courtesy of the Collection Fabrice Dassé, Pontoise

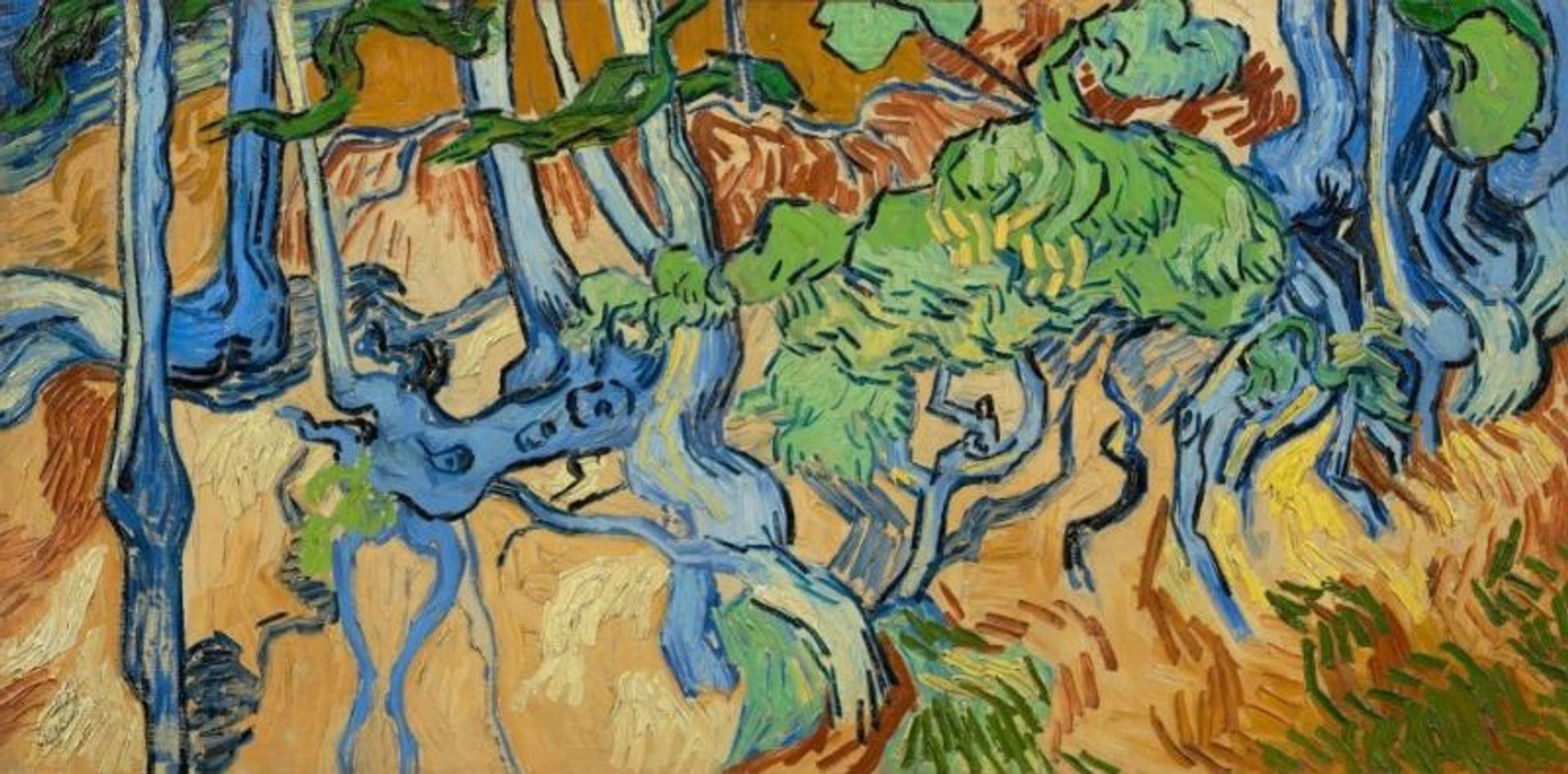

Van Gogh’s Tree Roots (July 1890) Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Another discovery was the confirmation of the actual spot where Van Gogh painted his final picture, just hours before he shot himself on 27 July 1890. A newly found 1907 photograph shows the roadside in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise with the trees that appear in this last painting, Tree Roots (July 1890).

And there were lighter findings, too. A Dutch trombonist uncovered documentary evidence to show that in 1884 Vincent was one of the financial supporters of a brass band that was being established in his parents’ village of Nuenen.

We all dream about discovering an unknown Van Gogh in our attic. This year several unseen or unrecorded works did emerge from obscurity, even if their private owners had suspected who the creator was. An important sketch of Worn Out (November 1882), purchased for £6 in the early 1900s, turned up with the Dutch descendants of the original collector. Three drawings of peasants (autumn 1881) had been preserved as a bookmark, hidden inside a volume on the French peasantry. And the watercolour View of The Hague with the New Church (January 1882), which had been sold for a few pennies in 1903, quietly passed through various private collections and ended up in Japan—we published it for the first time in colour.

Covid also seems to have had little impact on the Van Gogh market. The top lot this year was Wooden Cabins among the Olive Trees and Cypresses (autumn 1889), which sold at Christie’s in November for $71.4m, the second highest price for a Van Gogh since the Millennium.

Van Gogh’s Wooden Cabins among the Olive Trees and Cypresses (October 1889) © Christie’s Images Ltd 2021

Other works that sold this year are Young Man with a Cornflower (June 1890, Christie’s, $46.7m), The Bridge of Trinquetaille (June 1888, Christie’s, $37.4m), the watercolour Wheatstacks (June 1888, Christie’s, $35.9m), Montmartre Street Scene (February-April 1887, Sotheby’s, $15.4m), the drawing La Mousmé (July-August 1888, Christie’s, $10.4m), Still life: Vase with Gladioli (August-September 1886, Sotheby’s, $9.1m), Knot Birches (May 1884, Christie’s, $7.3m), and the sketch Potato Harvester (June-July 1885, Christie’s, $1.2m).

Exhibitions, on the other hand, were badly disrupted by Covid, with some postponed. The Didrichsen Art Museum in Finland made a valiant effort, mounting Becoming Van Gogh (with 40 works on paper from the Kröller-Müller Museum) from September 2020 to February 2021, along with a necessary closure for much of December and January. It attracted 46,000 visitors, a good result (considering the Covid problems) for this family-run museum on the outskirts of Helsinki.

Laura Owens’s 2021 installation at the Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles, including Van Gogh’s original painting Hospital at Saint-Rémy (October 1889), on loan from the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles Courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles Hq, London (photo: Annick Wetter)

The Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles, in the south of France, presented a show linking the work of Los Angeles artist Laura Owens with that of Van Gogh. Delayed by Covid, it ran from May to October.

Two of the exhibitions mounted at the Van Gogh Museum had a focus on Vincent’s work: Here to Stay: A Decade of remarkable Acquisitions and their Stories (June to September 2021) and The Potato Eaters: Mistake or Masterpiece? (from October 2021 to 13 February 2022). Although figures have not yet been released, the museum is believed to have welcomed just under 500,000 visitors to its permanent collection and exhibitions—less than a quarter of its normal pre-Covid level.

America did best when it came to exhibitions, particularly for those in Texas. The exuberant Hockney-Van Gogh: the Joy of Nature was presented at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, from February to June 2021. Van Gogh and the Olive Groves, based on years of research, opened at the Dallas Museum of Art in October and runs until 6 February 2022 (and then moves to the Van Gogh Museum). Through Vincent’s Eyes: Van Gogh and His Sources began at Ohio’s Columbus Museum of Art in November and coincidentally is also on until 6 February (and then travels to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art).

In terms of books, this year’s publications include Willem-Jan Verlinden’s The Van Gogh Sisters, on the life of Vincent’s three female siblings. Steven Naifeh’s Van Gogh and the Artists He Loved is by author of the key 2011 biography of the artist. And perhaps I could mention my own volume, Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame, which came out this autumn. In it I argue that Van Gogh died of suicide, rather than being shot by a local teenager.

Van Gogh Alive: the Experience, London, 2021 Credit: Martin Bailey

But the major event of the Van Gogh year was surely the wave of “immersive experiences” that swept the globe. There are several different touring presentations, of varying quality, in dozens of cities. The main attraction of them is to see Van Gogh’s motifs, his Sunflowers and Starry Night, blown up in huge detail. But it is quite a different experience from seeing his actual paintings.

My weekly blog has now been running for over three years. The most popular one this year may come as a surprise. It was not about a painting, but a frame—and a lost frame, known only from a newly discovered photograph. Decorated with sunflower motifs, this frame once protected The Artist on the Road to Tarascon (August 1888)—a painting that was probably destroyed by fire deep inside a salt mine in Germany at the end of the Second World War.

The blog Adventures with Van Gogh will be back after the holiday break, on 7 January.

Other Van Gogh news

The Cleveland Museum of Art recently opened a small display of its four Van Goghs, including two works on paper that are rarely shown: an early watercolour Landscape with Wheelbarrow (autumn 1883), Two Poplars in the Alpilles near Saint-Rémy (October 1889), The Large Plane Trees (December 1889) and the etched Portrait of Dr Gachet (June 1890). The watercolour was only presented for a short period to minimise its exposure to light, but the other three works will remain on show until 6 February 2022.

???

The display is titled There’s Nothing like the Real Thing: Van Gogh at the Cleveland Museum of Art—a direct reaction to the arrival of immersive experiences. One of these audio-visual presentations is confusingly promoted as “the immersive Van Gogh exhibit Cleveland”.