“I wanted to think about the emerging Saudi ecology in a global context,” says Philip Tinari, the Beijing-based curator of the inaugural Diriyah Biennale in Riyadh (until 11 March), which contrasted contemporary Saudi Arabia with China in the 1980s, when the country faced a similar relaxation of social and legal restrictions.

“First, to avoid terms like ‘catching up’ or ‘borrowing from’. Comparing this moment with that of China provides a different way into some of these questions. China is another country that’s quite different from the Western reality, and that’s prone to misunderstanding. How do you think about or contextualise the very specific and very precious energy of this moment of optimism and openness?”.

The framework was a punt for Tinari: China’s internal detente quickly seized up after 1989. And the biennial overall was a punt for Saudi’s ministry of culture, the behemoth-like organisation that only opened two years ago and which oversees the Diriyah Biennale Foundation; a specifically international exhibition for a country that has been shunned internationally. (The biennial was endlessly tagged as the “first Saudi biennial”—ignoring, perhaps, Desert X Al Ula, whose roll-out two years ago did not go nearly so well.)

Maha Malluh, Food for Thought, WORLD MAP (2021) Image: courtesy of Canvas and Diriyah Biennale Foundation

But it landed. While the choice of Tinari—the head of the UCCA in Beijing—might reflect the country’s economic and political shift towards China, it also allowed the biennial to join a lineage of biennials in the 1970s and 80s across the Arab region and South and East Asia, and latterly the Sharjah Biennial, in which Western art was the exception rather than the rule. Working with the curators Wejdan Reda, Shixuan Luan and Neil Zhang, Tinari delivered an exhibition that felt rooted in a Saudi context while also opening it up towards parallels in other countries, not just China but also African countries like Morocco, Kenya, and Egypt, for whom art served different means of defining a modern identity.

And while the dusty Riyadh air was thick with pronouncements of “game-changing” and even “world-changing,” the hyperbole was not far off. For the relatively isolated Saudi art scene, 2021/22 will be a moment of decisive shift.

Over the past two weeks, Saudi’s main cities of Jeddah and Riyadh disgorged a ludicrous amount of programming: the Diriyah Biennale, the highly important opening of Hayy Jameel, the Tuwaiq sculpture commissions for public art in Riyadh; Misk Art Week’s exhibitions and discursive programmes; the Jeddah edition of the roving Bienal Del Sur; the Red Sea International Film Festival; various pop-up events; and—last but not least—an art fair, Shara Art + Design. And the second edition of Desert X Al Ula, in February, is right around the corner.

Coming out of isolation

Saudi artists are calling it “the escape from the Dark Ages”, as the explosion of infrastructural growth finally matches the enthusiasm and activity that has been on the ground in Saudi over the past decade.

What is important is not just the amount but the international orientation. Saudi’s cultural policy has had three main priorities, explains Rakan Ibrahim Al-Touq, the general supervisor of strategy and international relations at the ministry of culture. The first is access to culture locally and the second is culture as a mode of economic growth. These have predominated so far, in programmes engineered towards raising Saudi quality of life, such as Riyadh Art, or in giving opportunities to the young population, such as Misk’s and the Red Sea International Film Festival’s grants. But now internationalism is on the make.

The historic district of At-Turaif in Diriyah © Diriyah Gate Development Authority

“The idea is to increase Saudi participation in global exchange,” Al-Touq says. “There’s an ambition to have more and more large- and small-scale platforms to make Saudi arts and culture professionals become part of the global conversation.”

One reason Saudi has been isolated is simply that no one could—or would—visit. But little by little, the circle of VIPs and enthusiasts around Saudi events has been widening, first to a regional network and more recently to a European and US one. Hardened biases and moral qualms about the country’s civil rights record following the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi seem to be easing. International collaborations and visibility are accompanying a more varied infrastructure, despite most of the projects still being government-led.

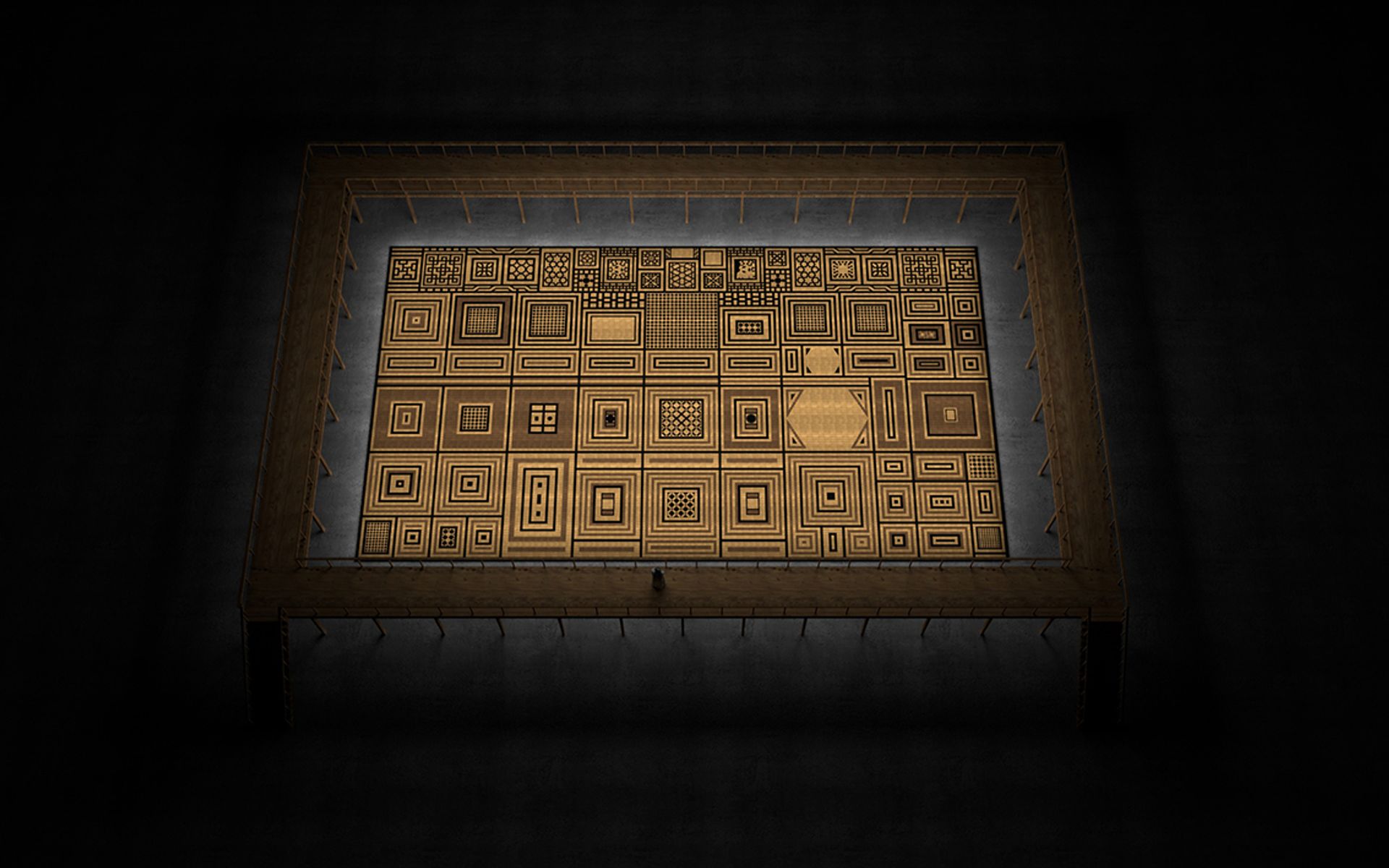

“The best thing about the biennial is for the local artists to get a better understanding and sense of international artists who are working at a high standard,” says the Jeddah artist Dana Awartani, whose re-creation of the destroyed floor of the Great Mosque of Aleppo was a standout of the biennial. “A lot of artists here are used to producing and selling at galleries or art fairs. We’ve not had a not-for-profit space, besides the Saudi Art Council. For me, the biennial is mostly educational—we need the whole infrastructure of education, from schools to universities, to spaces like Hayy that will give you stimulating workshops and talks and programming.”

Dana Awartani, Standing on the Ruins of Aleppo (2021) © Diriyah Biennale Foundation and the artist

Hayy Jameel creates a buzz

Hayy Jameel, which opened on 10 December, is a monument to devolved power—the epitome of Jeddah as a site of independent, grassroots art activity. The complex of buildings in the north of the city is non-governmental, run by the philanthropic Jameel family, and houses exhibition galleries to be programmed by Art Jameel, as well as spaces for commercial entities such as Athr Gallery, artist studios, editing suites, and Saudi’s first art-house cinema, among other spaces. (In line with their first exhibition around food and sustainability, curated by Jameel’s Rahul Gudipudi and the Delfina Foundation’s Dani Burrows, the artist Moza Almatrooshi offered beekeeping classes—which rather remarkably sold out immediately.) In bringing together all these strands, Hayy Jameel reflects currents on the ground—and it also elevates them into visibility, signalling their existence to those coming from abroad.

This makes even the architecture of the site a tricky proposition, in solidifying categories that were fluid before. Saudi watchers know that the future is foretold in blueprints. Contractors say bars are being built in the new Red Sea hotels, despite alcohol still being illegal—for now. Hayy Jameel, which was conceptualised in 2014, had to institute a shift midway through construction: the art-house cinema, now designed by the Jeddah firm Bricklab, was first conceived as a theatre, because cinemas were banned at the time. Part of the reason for its laissez-faire attitude about the purposes of its space, says its director Antonia Carver, is to keep this changeability alive.

“I’m fascinated by how the divisions between art forms we impose today were not so relevant in the past in this region — artists opted to make work in poetry, fiction, painting and set-design,” she says. “Hayy Jameel’s architecture and mandate aims to encourage the various disciplines to meld and cross-pollinate as they did more in the past. The four areas we focus on—arts, cinema, studios and learning—are reflected in the four blocks that face onto the courtyard; in terms of the programme, we have begun commissioning artists across media, and going forward have plans to develop this cross-disciplinary approach further.”

Zahrah Al Ghamdi, Birth of a Place (2021) Image: © Diriyah Biennale Foundation and the artist

War in the background

Similarly, Tinari’s comparison with China—which comes across heavier in the press material than in the more open show itself—allows him to gesture towards the complicated layering of state censorship, self-censorship, and misreadings that characterise art-making in the Saudi climate. Though internationalism brings opportunities, the stakes are still high on the ground. At the awards ceremony for the Tuwaiq sculpture prize, ballistic missiles flew overhead and exploded midair, intercepted by the country’s missile defence system. They were launched by Houthi rebels, a reminder of a less successful decision by the Crown Prince—the Yemen War—and of the autocracy and capriciousness of the Saudi state.

The crucial question of the coming few years will have to be internationalism’s effect on the art itself. Though to a smaller extent than during the years of social restrictions, Saudi artists often speak two languages in their work—one code of critique, or even mourning, and one code for foreign visitors. As Saudi opens up, which language will be heard? Or will a new, more streamlined idiom emerge—sacrificing complexity for international legibility?