For some reason, the art world doesn’t do annual awards. Almost every other industry pats itself on the back each year with glitzy galas and plastic prizes. But there is no equivalent of the Golden Globes for museums or the art market, perhaps because we dare not stop taking ourselves frightfully seriously. So, to encourage change, allow me to introduce the inaugural Diary of an Art Historian awards.

Bernardo Bellotto's The Fortress of Königstein from the North (around 1756-58) © The National Gallery, London

My Exhibition of the Year is Bellotto: The Königstein Views Reunited at the National Gallery in London. Understated in its presentation—one room, five paintings and some labels—this was a show that let the art do the talking. And for sheer “how do they do that?” magic, few artists rival Bellotto. Seeing all five of his views of Königstein was like travelling back in time to 18th-century Saxony, the sense of walking among Augustus III’s rocky citadel created not just by the extraordinary verisimilitude of Bellotto’s buildings and trees, but almost imperceptible details like the gently edged, long shadows to convey warm evening light, and the clothes hanging from a laundry line just a few degrees off vertical, because there’s a slight breeze. I found it mesmerising. A special commendation for allowing photography, too.

In this version of the painting of the Frey children, attributed to Jacques Guillame Lucien Amans (1837), only three children can be seen and just a shadow of Bélizaire, a domestic servant for the Frey family, is visible beside the tree Photo: © CHRISTIE'S IMAGES / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

A line in a ledger in the archives of the Evergreen Plantation in Louisiana notes the sale in 1856 of a young slave named Bélizaire for $1,200. As for millions of American slaves, the transaction might have been the only record of his life were it not for an amazing piece of research by the historian Katy Shannon, who has identified Bélizaire in a portrait painted around 1837. The portrait itself is a remarkable discovery, having been deaccessioned by New Orleans Museum of Art in 2005, when it appeared to be an unremarkable portrait of three unknown white children. But when the picture was cleaned, after fetching just $7,500 at Christie’s in New York, a portrait of a Black child watching over the children was found, having at some stage been painted out. And now, thanks to Shannon’s research, we know who the children are—members of the Frey family—and the name of the child obliged to be their servant, Bélizaire. The opportunity to posthumously recognise, and celebrate, a child born into slavery almost two centuries ago is therefore my Discovery of the Year. And a warning against deaccessioning.

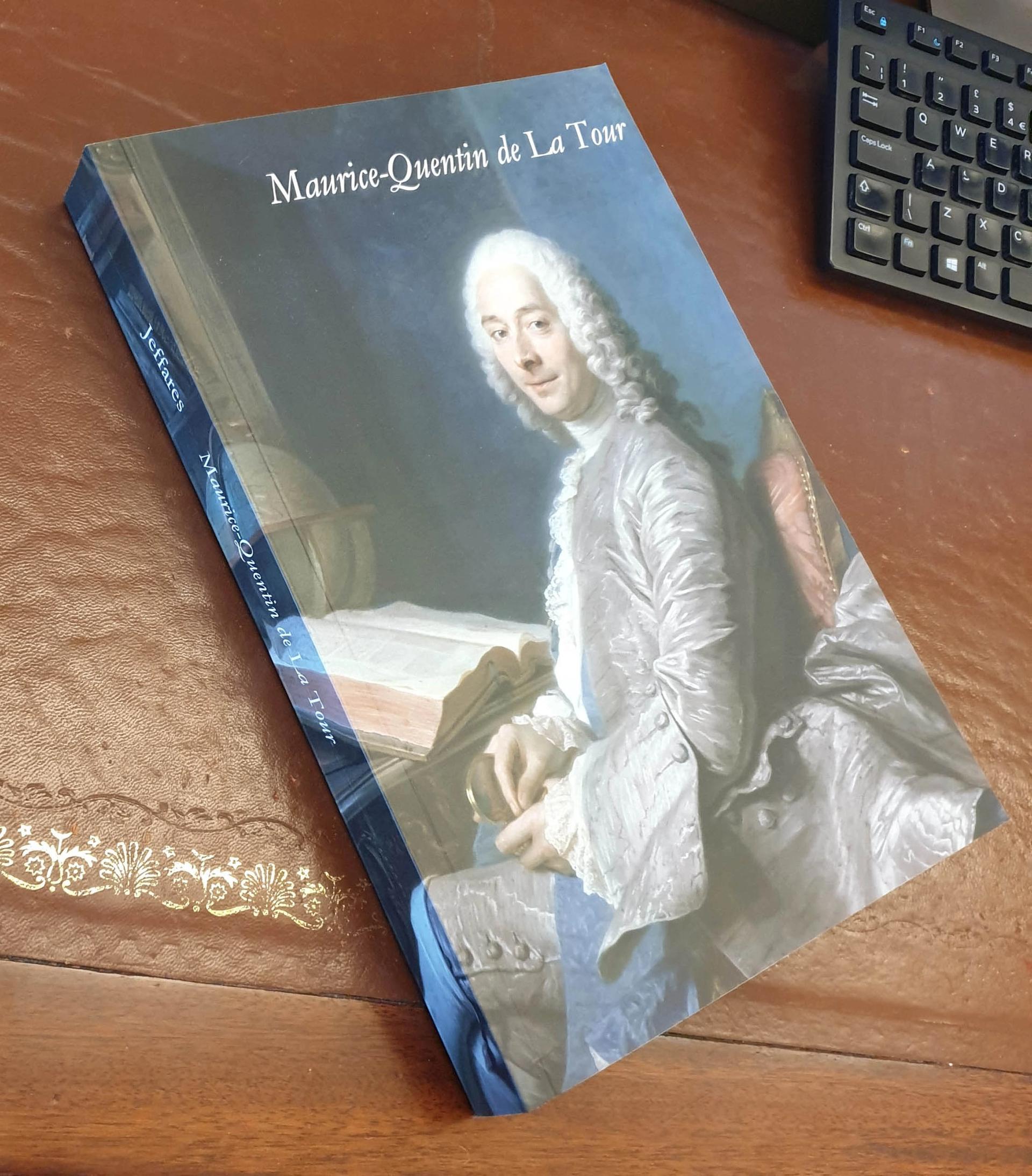

There is only one printed copy of Neil Jeffares’s catalogue raisonné of the pastels of Maurice-Quentin de La Tour—the catalogue has been published online and is free to access

As an academic discipline, art history is still beset by barriers and gatekeeping, one of which is the perception that new research only carries weight if published by an established imprint, and in a book or journal that most people can’t afford. For this reason, and for being a brilliant and indispensable piece of work, my Book of the Year is Neil Jeffares’s catalogue raisonné of the pastels of Maurice-Quentin de La Tour. I say book, but there is only one printed copy, Neil’s own, for the catalogue has been published online. It is free and a joy to use, with links to reproductions and further reading, and every known document relating to La Tour’s life searchable in seconds. The catalogue might not yet have the kudos of a book published by Yale priced at £150, but it will have a thousand times more readers, and just as impressive a legacy.

Mona Lisa in the manner of Leonardo da Vinci (around 1900) Courtesy of Sotheby's

Finally, the award for Auction Consignment of the Year goes to whoever had the imagination to capitalise on Leonardo-mania by buying a humdrum, probably early 20th-century copy of the Mona Lisa on eBay for £2,750 and swiftly consigning it to Sotheby’s Old Master sale in London, where it made £378,000.