For four months in 1961, viewers in 38 countries tuned in to watch the trial of Nazi high official Adolf Eichmann being televised from Jerusalem. Eichmann’s trial was the first-ever to be internationally broadcast, airing Holocaust atrocities to a worldwide audience and creating a dramatic shift in public consciousness about the Second World War. From within his bulletproof glass box in the courtroom, Eichmann stood charged with coordinating the mass deportation of European Jews to ghettos and concentration camps where they were ultimately murdered. Unlike the 1945-46 Nuremberg trials, which used documents to try former Nazi officials, the Eichmann trial relied heavily on live testimonies of Holocaust survivors, adding a vivid human dimension to the accusations.

Watching the proceedings from afar was Argentinian-American artist Mauricio Lasansky, who had been preoccupied with Nazi atrocities since the mid-1940s and was distraught at learning that Eichmann had lived freely in his native Buenos Aires for a decade prior to the trial. By the time Eichmann’s verdict was announced on 13 December 1961 by a panel of judges who found him guilty of crimes against humanity and war crimes, Lasansky began working on The Nazi Drawings—a series of 33 largescale drawings now on view in a dedicated exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia), titled Envisioning Evil.

“When I made The Nazi Drawings, I made them as an angry young man,” Lasansky said in an interview conducted for the catalogue that accompanied his 1976 traveling retrospective. “I wanted to spit it out, my point of view, no rules, no nothing, an instinctive reaction.”

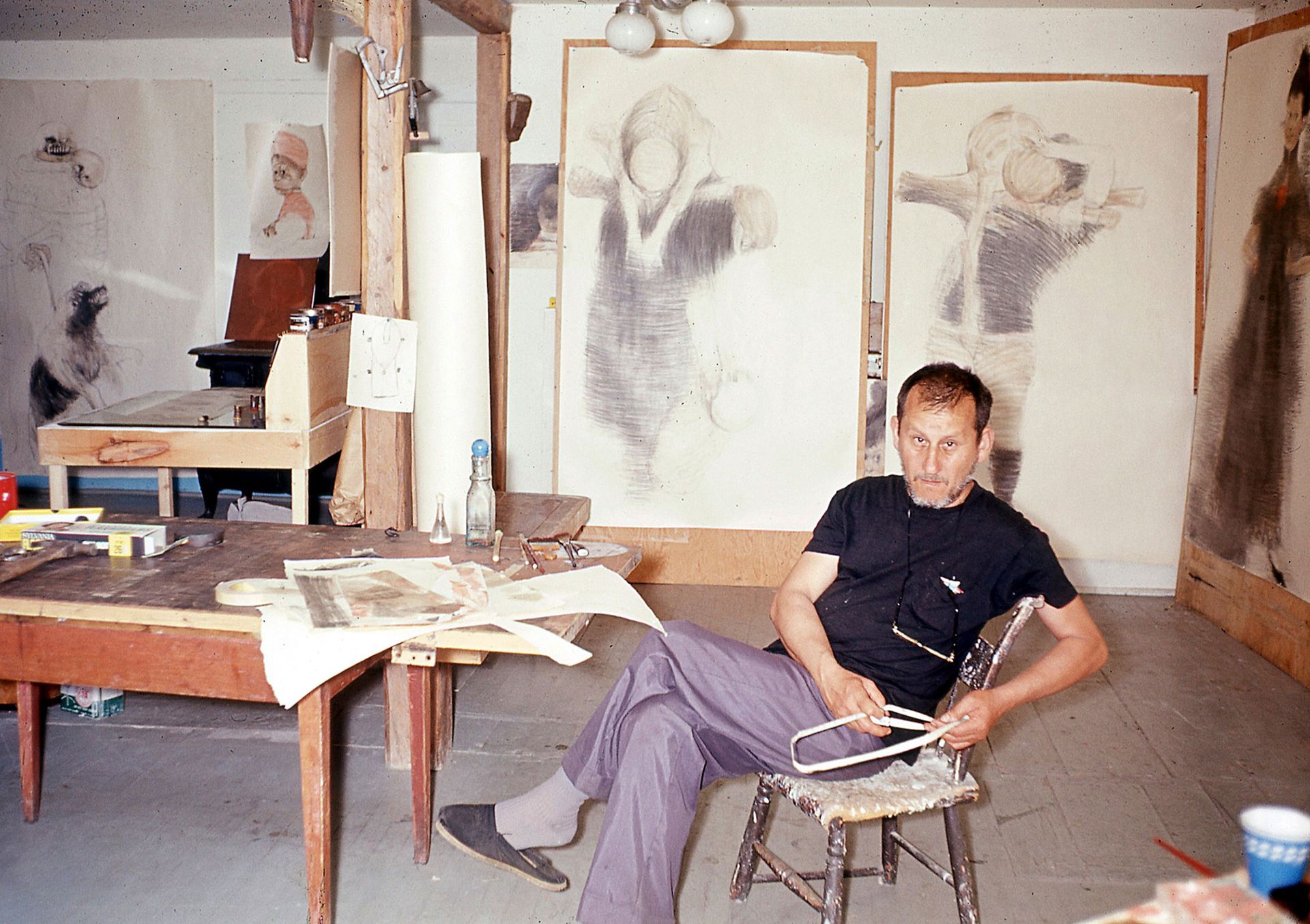

Mauricio Lasansky working on “The Nazi Drawings” in his studio in 1962, Vinalhaven, Maine Photo courtesy the Lasansky Corporation

The series was shown in a nine-city tour between 1967 and 1970, drawing large attendance and increasing Holocaust awareness among viewers. The traveling exhibition opened at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and was among the inaugural exhibitions at the Whitney’s new Marcel Breuer-designed building in 1967 before continuing to the Indianapolis Museum of Art and Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, among other venues.

“We are the prurient observers, the guilty bystanders who survived these terrors of human history,” wrote poet and playwright Edwin Honig in the accompanying exhibition catalogue.

The current catalogue published by Mia is the first publication devoted to The Nazi Drawings since its original tour. “It was our task to really contextualise The Nazi Drawings,” says exhibition curator Rachel McGarry.“To consider how the original visitors saw them, what the artist is thinking about, and what specific issues are being debated at the time.”

Lasansky often worked on themes of social injustice, war and human suffering, but was primarily a master printmaker, which made his choice of drawing for this series unusual. “I tried to keep not only the vision of The Nazi Drawings simple and direct but also the material I used in making them,” Lasansky shared in the original exhibition catalogue, referring to his use of pencil. “I wanted them to be done with a tool used by everyone everywhere.”

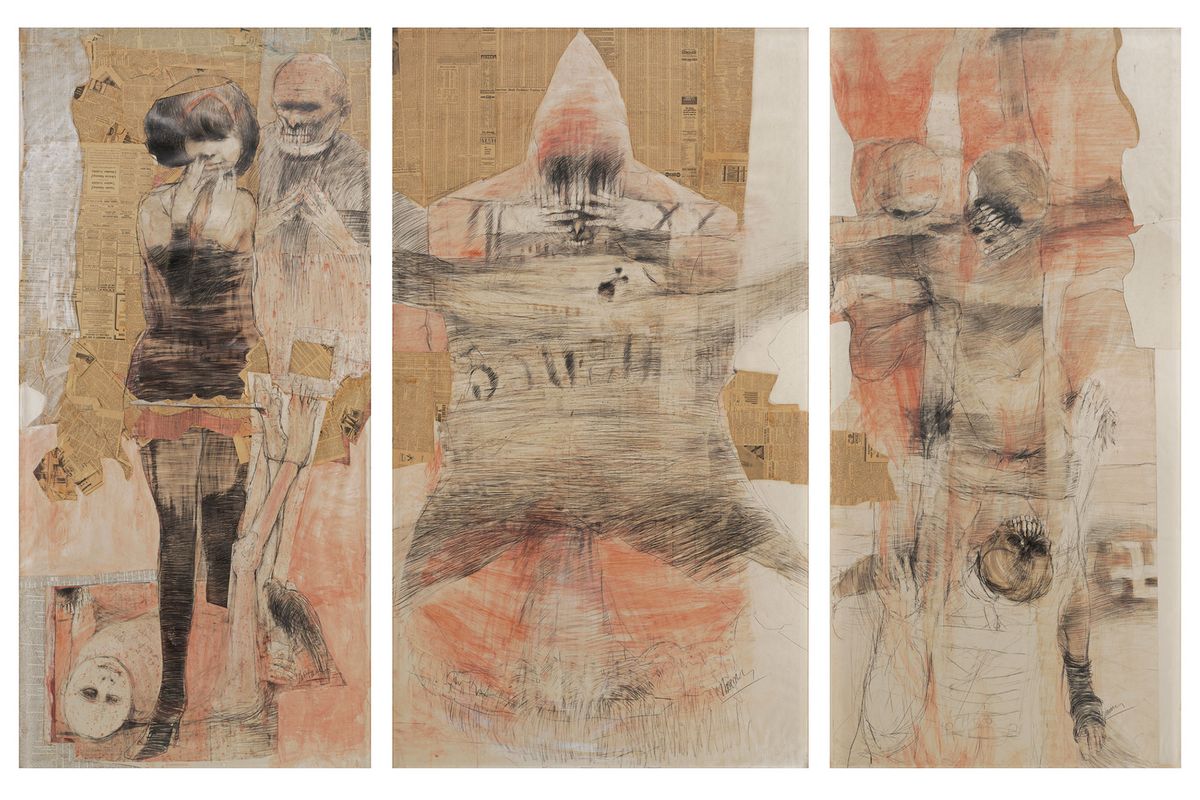

Lasansky sketched staccato, serrated lines in a limited palette of black, white, and red, offset by yellowing pages of collaged newspaper clippings. He handled the large sheets of paper brutally, ripping and lining them with pinholes. Once completed, he numbered these monumental works on paper instead of titling them. The overall name of the series, however, was intended to express universality and refer to all victims of the Nazis.

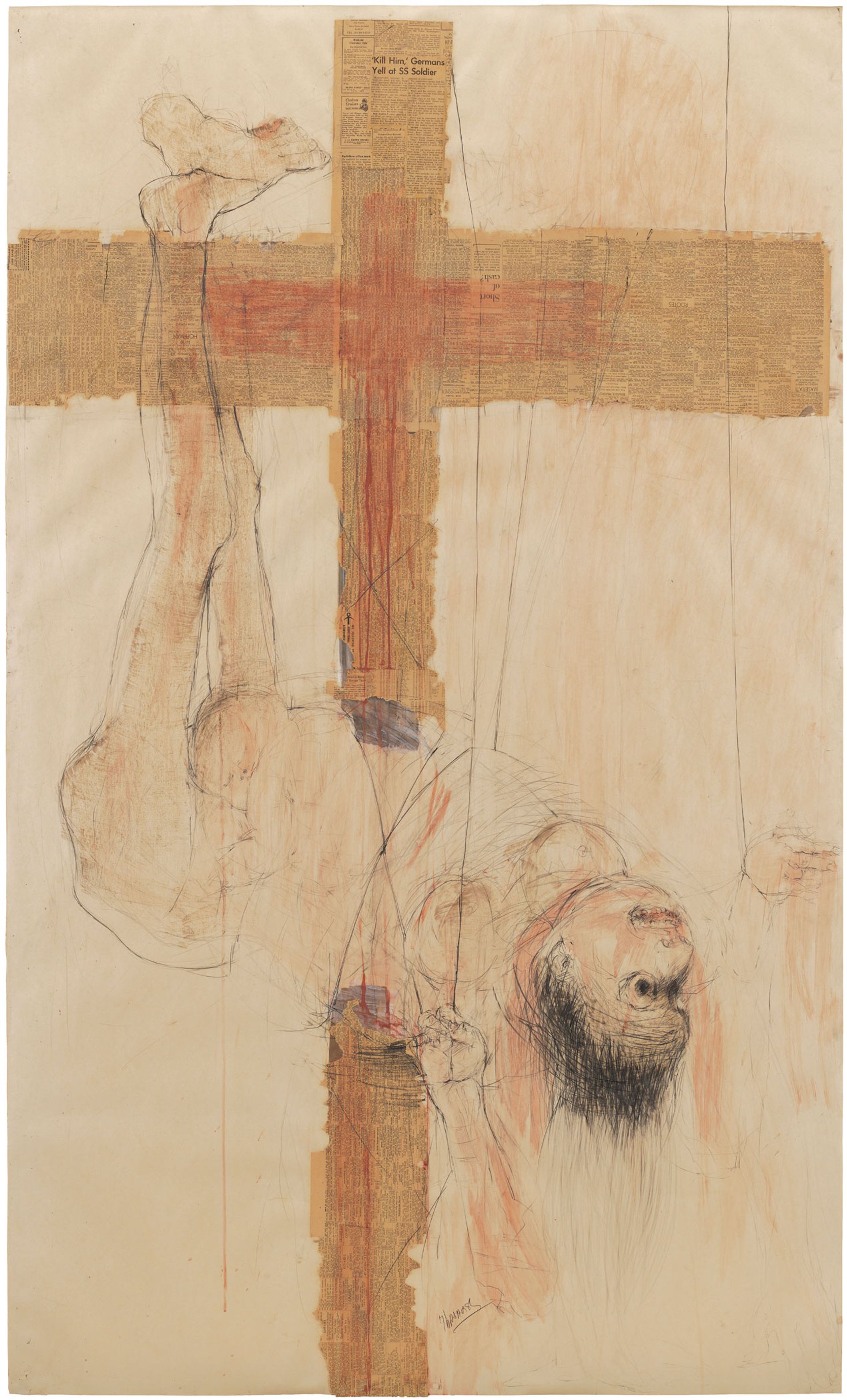

Mauricio Lasansky, No. 18 (1961-63), from “The Nazi Drawings”, Levitt Foundation © Lasansky Corporation

The opening works in the series depict Nazis wearing menacing skull-helmets. “The first drawings [Lasansky] produces are those lone Nazi soldiers, right at the moment when everybody is considering Eichmann and how this rather ordinary man in the glass box was a horrifying mass murderer,” says McGarry. “The second part of the series looks at the victims—mothers and children—that really reflects on the televised trial that broadcast 90 survivors testifying.”

Other works in the series illustrated sexual violence towards women (such as concentration camp brothels, and other forms of sexual slavery), the murder of women and children, the inaction of the Pope, and No. 30 is a self-portrait of the artist being tormented by a skeleton as he draws using a utensil dripping with his own blood. Lasansky portrays these difficult subjects using the storied visual iconographies of crucifixions, pietàs and dancing with death.

“I was frankly really worried about how such a dark, serious show would be received—especially coming out of a global pandemic,” admits McGarry, who has been surprised by consistently full galleries since the exhibition opened on 16 October. “But it turns out, the public is really hungry for serious art at this moment. We’re living in a really serious time and coming to grips with a lot of major historic events.”

- Envisioning Evil: ‘The Nazi Drawings’ by Mauricio Lasansky at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minnesota, until 26 June 2022