Since she graduated from the Royal Academy Schools in 2019, Rachel Jones has gained significant attention. Last year, Jones—who is based in Essex, UK—joined Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, where she is about to open a solo show, and in March 2022 she has her first UK institutional exhibition, at Chisenhale Gallery. She already has works in the collections of Tate, Arts Council England, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, and the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami.

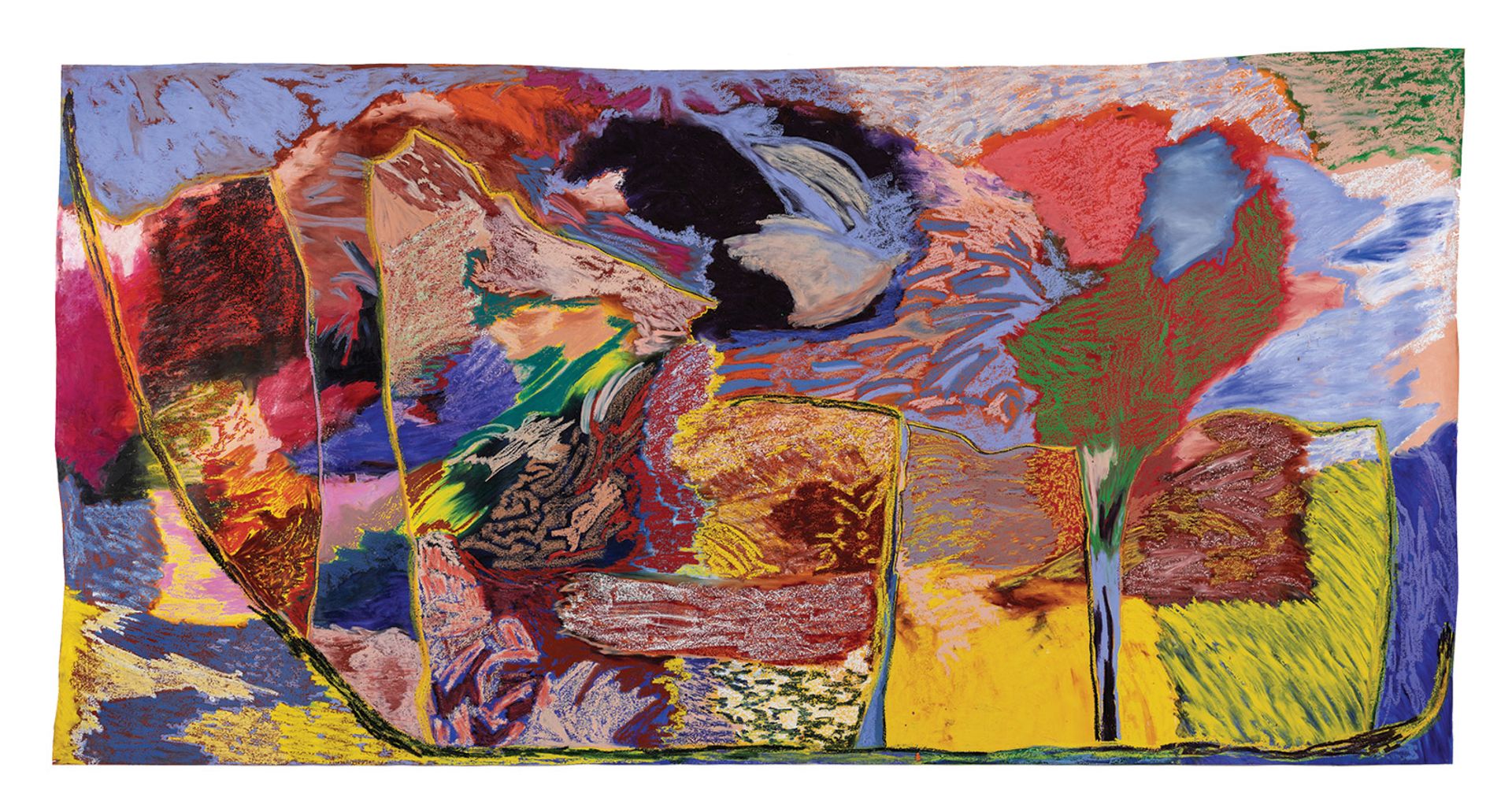

The clamour to show her is unsurprising: one of the most arresting works in Mixing it Up: Painting Today, the Hayward Gallery’s survey of 31 painters (until 12 December), is a 7m-long canvas by Jones, who is one of the youngest artists in the show. At first glance the massive work appears to be an entirely abstract composition of kaleidoscopically coloured marks and gestures, rendered in pastel and oil stick. But on closer scrutiny it reveals the outline of a huge row of bared teeth, a subject confirmed by its evocative title, lick your teeth, they so clutch (2021). Jones has described her distinctive approach to abstraction as “using motifs and colour as a way to communicate ideas about the interiority of Black bodies and their lived experience”, and the teeth that frequently feature in her vivid, boldly gestural works act as social, cultural and emotional signifiers, freighted with contemporary and historical meaning.

The Art Newspaper: Does the work you are making for your show SMIIILLLLEEEE at Thaddaeus Ropac still feature teeth? The title of the show seems to imply that it does.

Rachel Jones: There are lips and mouths but also flowers. I started to use flowers in my last body of work lick your teeth, they so clutch and they have carried through to the paintings for Ropac.

Why flowers?

It’s about trying to broaden the lexicon of imagery and also to give people who might already be familiar with the teeth an opportunity to think about them in different ways so they can see them interacting with different shapes and patterns. The symbol of a flower means different things in different contexts in correlation to the lips and the teeth. With the lick your teeth series, I was looking specifically at teeth adornments like grills and gold tooth caps and their prevalence in Black culture. The flower became repeated as a form to emphasise the idea of having a pattern, or something stuck on the tooth. But now I’m using flowers in different ways and in various scales: sometimes a flower takes up a significant amount of the canvas and other times it takes time to recognise that it is there.

You patrol a porous line between abstraction and the figurative. When did isolated parts of the body start to feature in your work?

Early on when I was making life drawings, I developed a practice where I would only draw certain parts of the body and abstract them, and at the Royal Academy Schools I started to use the body, or parts of the body, to think about a broad spectrum of feelings, emotions and experiences. In 2018 I showed a series of small drawings that had eyes in them. This stemmed from thinking about experiences I’ve had where people look at me and how that raises a sense of hyper-visibility and sensitivity to being looked at, and especially being a Black woman being stared at by people. And the idea that all these emotions—desire, inquisitiveness, hostility—can be communicated just through a stare. From then on, I decided that this was something that I could develop.

A Sliced Tooth (2020), in the collection of the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami

What attracted you to focus on the mouth?

I just felt most connected to, and interested in, the teeth and mouth drawings that I was making. They seemed to encompass so much, while also speaking to as many people as possible: everyone has a mouth, and everyone understands what it is to have pain in your mouth and your teeth, or for that to be a site of pleasure, or for things to be expelled from your body in quite a violent way through your mouth. It sits at different register points for people in a way that is relatable, but also more specific, depending on who the person is, or what their cultural history, race and gender are. And so this enabled me to talk about lots of things all at once, without being didactic or saying that I have this specific message that I want to communicate that you must understand. It is about allowing the viewer to dictate for themselves what it is that they see or what they experience.

This desire for a subjective engagement also seems to tie in with your use of vivid colour.

Colour was also really important, because I felt that the way I use colour could do a lot of that work for me, where it was evoking or provoking something and communicating in a way where it operates in a different sort of register to how people may be used to thinking about how colours interact. I suppose it’s about trying to be led by the process as much as possible, and trying not to limit the potential for the work to exist in different ways and in different spaces and contexts.

The mouth is also a liminal space, between the body’s interior and exterior.

Yes, it crosses over to different things at the same time. Having a simple starting point with a mouth and teeth suddenly becomes infinite in its possibilities.

Although it has figurative elements, overall your work seems rooted in the sheer joy of abstract colour, form and gesture—where does this come from?

The things that I was most drawn to and moved by as a younger artist, and even as a child, often tended to be by Abstract Expressionist painters. I also responded to things that were abstract in the sense that they were removed from a reality that was day-to-day. Even looking at cartoons, and thinking about them as a space which is abstracted with violence and shape and things being over-exaggerated, or so imaginative that they go beyond an understanding of what exists in real time or a real space. Those sorts of viewing experiences really helped me understand that you can use colour and shape and form to speak to people in a way that isn’t about a spoken language—it’s about emotion and inciting feelings that don’t have to be explained or expressed. It’s responsive, it’s instinctive, and a core part of all of us. So for me, it came from a place of being intrigued by these things and understanding them as a base human desire, and wanting to figure out how I could fit within that history and explore my interest in representations of Blackness.

You’ve talked about wanting your viewers to feel with their eyes.

The dream is for you to have that moment of thinking about the image or colour and then to go outside of that, and think about how it relates to things that are from your own life or from your own understanding of art. The idea of what it is to feel a shiver go from your spine up your body. For things to get out of the realm of just seeing and instead sit within a situation of being able to connect to memory, or history, or a physical sense of being really seated in your body. Those sorts of ideas are what I pin the work on.

Another painting from Jones's SMIIILLLLEEEE series

Photo: Eva Herzog. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac gallery

You make your work using pastel and oil sticks rather than with paint and brushes—why?

It’s not to say that I won’t go back to painting, but for me there’s this relationship to drawing that is very immediate and there’s a sense of being able to produce something out of nothing, imaginatively and quickly without any pressure. I’ve always been interested in how to move away from the glory that’s attached to being a painter or to making a painting which I find quite intimidating and also redundant. Painting is as relevant as every other art form, but it can sit in this territory of being quite aloof and distant, and I’m not interested in that kind of position as a painter. Drawing doesn’t operate like that, it’s the thing that people do every day. It’s a form of communication that we all understand and feel maybe less distance from than the history of painting.

Nonetheless your work presents a rich variety of very painterly marks and passages.

I wanted to try and use drawing in the practice in a way that was just as serious and meaningful to me as painting was, and so I decided to use oil sticks and pastels. This was partly because of the colour: the pigment is amazing. And the way you can use and manipulate them as a material is fantastic. I’m still learning new ways of blending and layering, and it’s really exciting to have a material that constantly seems to evolve. There’s also this attraction to the idea that it is oil, it’s the same substance that paint is, so there’s this crossing again, this liminal thing of being neither one thing or the other, but both.

There’s also both an immediacy and an intimacy to drawing.

I don’t plan any works so I don’t ever really know what they are going to look like; it’s completely intuitive, so it’s nice to have a material that can be picked up and used immediately. There’s no interruption in the connection between my body, the material, and the surface—I can channel things through the colour into the work, and the cycle isn’t broken. It’s like a continuous stream of thought and relationship between the material, my ideas—what I’m thinking or how I’m feeling—and then the surface of the paper or the canvas. It just seems really natural and immediate, and it’s the truest sense of being able to communicate through oil that I’ve ever experienced.

You often work on a very large scale—is this also a deliberate strategy to challenge hierarchies around painting and drawing?

Definitely. I actually find it more difficult and challenging to make smaller paintings than larger ones. So for me, it was about setting up my practice where there were challenges for myself and I was being pushed to work outside my comfort zone. It’s also the idea of being able to use things that are just lying around in the studio: we live in an age of waste, we’re in an ecological crisis, and I don’t take for granted the time and the resources that I have available to me, I want to make the most of them. So when I have random bits of paper or canvas around me, I use them, and their shape or surface dictates the type of image that I produce. I love the fact that there are all these technical things that also add a sense of content and texture to the work that are completely out of my control.

Language seems to be another important factor—your titles are fantastic.

I think it’s fair to say that I read more than I look at art. And I draw more from literary sources than I do from anything else. Language is also very important in thinking about how to position the viewer in different places. The first titles I used were descriptive, they were meant to be evocative of feeling either pleasure or pain in the mouth, or there was the idea of the mouth being the central point that someone should enter the work from. It was trying to give people an access point without being literal whilst also painting another picture in their mind’s eye, alongside the one they were viewing. But in the most recent titles there’s been a shift towards instructing someone, or the idea of a voice speaking the title. Familial language is used to reflect Black communities, and I use colloquialisms to address a specific group of people. Certain things might not be understood by everyone, so it depends on the position of the person who’s looking at the work, or reading the title, what they gain from it. For me there’s always a sense of wanting to be generous, but also having a direct line of communication to the audience that I prioritise the most. And that’s a Black audience. The titles give opportunities to do that, to think about language that is familiar to me or ways that I might speak with certain friends and family, and giving that a space to be shared and accessed, but without being exclusive. It doesn’t have to be known that the words are personal, but I think changing the tone and planting the idea of there being a voice behind it gives the work another lens to be seen through.

What are you planning for the Chisenhale?

It will be a series of paintings, and I’m interested in carrying on with the motifs of the flowers and the teeth and lips. As it’s my first institutional show, it’s also the first opportunity I have to make work which sits outside of what I would normally do in the gallery. It’s a real relationship of reciprocity with [Chisenhale senior curator] Ellen Greig and [director] Zoé Whitley in helping me develop and push the practice, and think about developing the language of the paintings. If I speak about the work coming from a place of my inner self and being, and wanting to provoke emotions in people, then that isn’t going to be discarded when I have interactions with people about how the work might be made or exist in an exhibition.

Last year you signed up with Thaddeus Ropac, one of the world’s leading art galleries. How are you navigating the elitist, privileged and still predominantly white contemporary art market?

I basically see being represented by the gallery as an opportunity to reach the people that I want to reach, in a way that I didn’t imagine would happen this quickly. And then also having the means of still being able to show with spaces more rooted in a project space setup. It’s nice to have both things happen within proximity to each other, because I feel like the audiences that might go to a smaller space aren’t the same as those that will come to Ropac. It’s nice to have that position of visibility, and I’m excited for the work to be received within different spaces and contexts, and for people to see how I address that. It’s about reaching as many people as possible and focusing on the work and how I want it to evolve.

• Rachel Jones: SMIIILLLLEEEE, Thaddaeus Ropac, London, 8 December-5 February 2022; Chisenhale Gallery, London, March-May 2022, dates to be confirmed

Biography

Born: 1991 London

Lives: Essex, UK

Education: 2013 BA, Glasgow School of Art; 2019 MA, Royal Academy Schools

Key Shows: 2021 Mixing it Up: Painting Today, Hayward Gallery, London; 2020 Gallery 12.26, Dallas, Texas; Thaddaeus Ropac (group show), London; 2019 Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas; New Art Centre, Salisbury, Wiltshire, with Gillian Ayres; 2018 Jupiter Woods, London

Represented by: Thaddaeus Ropac, Salzburg, Paris, London