Inner-city community centres designed by prize-winning architects are a rarity even outside a time of pandemic and austerity. And those involving a leading artist in every aspect of the construction from the façade to the toilet tiling are even more unusual. But Holborn House, which opened last week in Bloomsbury, central London, is just such a building.

Situated in a small alleyway just off Lamb’s Conduit Street, this new London landmark is the creation of 6a Architects, a practice much loved by the UK art world and beyond. In 2019 6a, run by Stephanie Macdonald and Tom Emerson, were the winners of a double award from Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) for their new Milton Keynes Gallery, and three years earlier their photography studio for Juergen Teller also snagged more RIBAs and a Stirling Prize nomination.

Other highly regarded 6a commissions have included the expansion of the South London Gallery and full refurbishment of its Fire Station outpost, halls of residence for Churchill College Cambridge, the design of Sadie Coles’s Davies Street space and the conversion of two 18th-century Spitalfields weavers houses into Raven Row Gallery.

Holborn House is situated in a small alleyway just off Lamb’s Conduit Street, London

Now 6a have joined forces with artist Caragh Thuring to transform an old basement gymnasium buried within a city block into a new two storey street-facing community building for the Holborn Community Association (HCA), which has occupied the site for the past 100 years.

Thuring is best known as a painter but for Holborn House she has created an integrated, multi-stranded scheme that permeates every part of the building in what is her first permanent public artwork. Three artists were invited to apply but despite her inexperience in the public realm for 6a, Thuring was the obvious choice. “We loved Caragh’s work—the architectural iconography of place and the spatial depth in her canvases is fantastic,” says Stephanie Macdonald, who sees Thuring’s work as a crucial factor in establishing the centre’s overall presence and visibility within what, despite Bloomsbury’s artistic and literary heritage, is also a densely built, low income, culturally diverse inner-city borough.

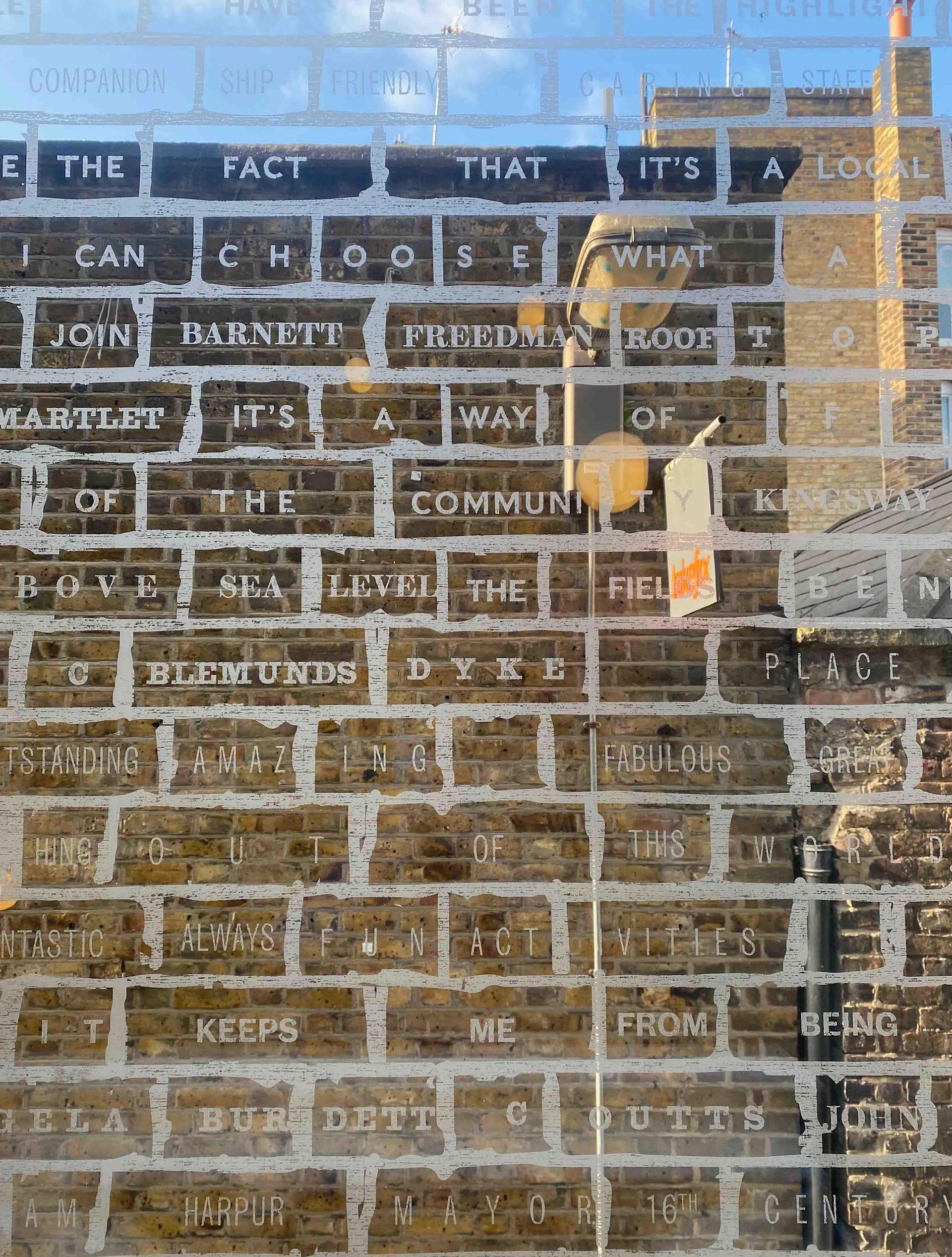

The most conspicuous element of Thuring’s scheme is Great Things Lie Ahead, an etched glass work which covers the entire façade in a series of large glazed panels that expose the steel structure and interior spaces of the new Holborn House, “It makes the building feel protected but also transparent” says Macdonald. Both functional and adorning, this transparent membrane has been etched with the outlines of bricks and mortar taken from the surrounding buildings, which span the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.

Caragh Thuring's Great Things Lie Ahead (2021)

Inscribed into this ghostly brickwork tracery are words which, in a range of fonts, allude to the rich and multiple histories of the site, its surroundings and its communities past and present. There are phrases, personal testimonies, names of places as well as individuals both famous and lesser-known, gleaned from Thuring and Macdonald’s extensive research as well as from workshops and interviews with local people and HCA members. (The work’s title, Great Things Lie Ahead comes from old archive scrapbooks dating from the 1920s.) “I wanted to create something welcoming and timeless that conveyed the past, present and the future – a sort of time travel,” says Thuring, who described her process as “mapping and expanding the actual place of the building, the landscape, the people who have passed through, do now, and will pass through in the future”.

Thuring’s work also features on the acoustic panelling in the upper storey of the gymnasium where, in fabric form, her brick motif appears as a frieze woven by the Suffolk company that make the textile elements she incorporates into her paintings.

Interior view of Holborn House

The tiles in the new kitchen, shower rooms and toilets also reflect the distinctive off-kilter palette of Thuring’s paintings which is offset by vivid green metalwork and stair rails, which are apparently also a nod to Holborn’s distant past as a favoured forested hunting ground for the mayor of London in the 16th century.

The budget for Holborn House was modest, with funds tirelessly raised by the community association as well as the design team. For the project has special significance for MacDonald and Emerson who are locals and, along with their now-adult son, have been regular participants in the many activities offered by the HCA over the years. “We were living in a one bedroom flat with no garden so we came here for soft play, baby gym, ballet classes, birthday parties and art and photography workshops,” says Macdonald. “It’s been a key part of our lives for two decades.”

Architect Stephanie Macdonald and artist Caragh Thuring. Courtesy of Louisa Buck

Now 6a and Thuring’s new, highly insulated, low energy and fully accessible building allows HCA to significantly increase the number of people it supports on a daily basis. New and versatile studios, changing rooms, work spaces and club rooms have immeasurably expended its facilities and scope. Although fabrication expenses had to be honed, every attempt has been made to use the best quality materials with Macdonald and Emerson pulling in favours from across the design sector to get the best paint, signage and furniture, at cost.

Holborn House has the best Arper chairs, Little Greene paintwork and signs by John Morgan, who also worked with Thuring on the façade typography. Other collaborations that reflect this exacting attention to detail include a detailed planting scheme from esteemed horticulturalist and garden writer Dan Pearson, that over time will add a crucial green element to the alleyway entrance and roof spaces.

“Why should the community always be fobbed off with the cheapest materials and solutions?” says Macdonald. “We want to give the people who work here and use the building the respect they deserve!” Now let’s also hope that this unique public building sets a new standard for what all communities across our cities and boroughs need and deserve—especially at this time. But at least in Bloomsbury, thanks to the vision and determination of this determined group of individuals, great things now truly do lie ahead for Holborn House and beyond.