Lawrence Weiner, an American conceptual artist best known for his public installations featuring enigmatic words and phrases with graphic accents, died on 2 December at age 79, his galleries Marian Goodman and Lisson confirmed.

Weiner rose to prominence in the late 1960s when conceptual art was gaining traction in the US. He was part of a generation of artists questioning conventional modes of making and displaying art. At the time Weiner was creating grid-based drawings, shaped canvases and ephemeral interventions that sought to delineate public spaces.

The response to one project from this era, for an exhibition organised by his gallerist Seth Siegelaub at Windham College in Vermont, led the artist to the breakthrough that would come to shape his practice for the next five decades. Students at the university cut the twine Weiner had erected on a campus lawn to delimit a grid because it obstructed their path. The artist realised the piece, A SERIES OF STAKES SET IN THE GROUND AT REGULAR INTERVALS (1968), could have been just as effective as a set of instructions.

Lawrence Weiner, AS FAR AS THE EYE CAN SEE at Whitney Museum of Art, New York, 2008 Photo by Sheldan Collins. Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery. © 2021 Lawrence Weiner / ARS, New York

“It became obvious to me that as long as you can present it, it didn’t matter how,” Weiner recalled in an oral history interview with the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art (AAA) in 2018. “Either you built it, you didn’t build it, you put in language, you didn’t put it in language, as long as it wasn’t a secret.” This ethos effectively became the artist’s lifelong manifesto.

Thereafter, many of his works followed this logic, with his text interventions often executed by others according to detailed directives. Often the works’ words would reference their contexts directly, such as interventions on New York City manhole covers with the phrase “IN DIRECT LINE WITH ANOTHER & THE NEXT” or the 2008 piece installed on the exterior of the Bass Museum in Miami Beach, SHELLS USED TO BUILD ROADS POURED UPON SHELLS USED TO PAY THE WAY, AT THE LEVEL OF THE SEA.

Lawrence Weiner, SHELLS USED TO BUILD ROADS POURED UPON SHELLS USED TO PAY THE WAY, AT THE LEVEL OF THE SEA (2008), at the Bass Museum, Miami Photo by Zaire Kacz. Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery © 2021 Lawrence Weiner / ARS, New York

His works in galleries and museums tended to refer poetically to relations between people, materials, space and the passage of time, like 1970’s EARTH TO EARTH ASHES TO ASHES DUST TO DUST, which is in the Guggenheim’s permanent collection. When executed in a non English-speaking country, his works’ texts would be rendered in both English and the local language, underlining the openness and accessibility of his practice.

“I don't know why they were so frightened,” Weiner recalled, in the Smithsonian interview, of the early reception of his work. “But those are the people now who make retrospectives of it.” In 2007-09, a major traveling retrospective of Weiner’s work was shown at the Whitney Museum, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and the K21 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf.

“Lawrence gained international recognition for the use of language as his primary medium,” Marian Goodman wrote in a statement. “He proposed a new relationship to art and redefined the position of the artist, and his works demonstrated the power of language worldwide.”

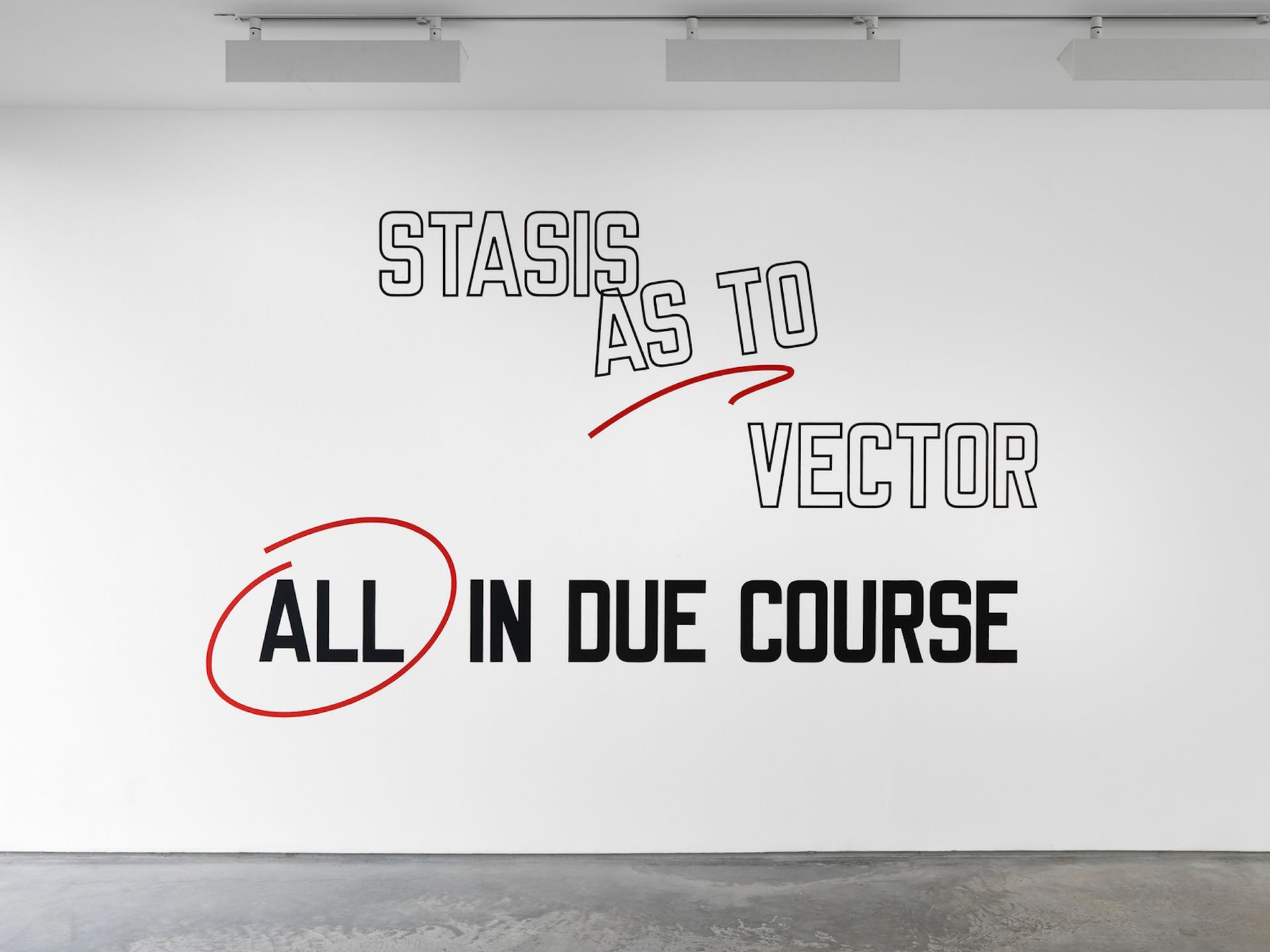

Lawrence Weiner, STASIS AS TO VECTOR ALL IN DUE COURSE (2012) © Lawrence Weiner. Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Weiner was born in New York in 1942 and grew up in the Bronx. After graduating from high school he traveled across the US before returning to New York and had his first show with Siegelaub in 1964. By the 1970s he was showing regularly at institutions in the US and Europe, and was included in both Documenta and the Venice Biennale in 1972.

In the ensuing decades he showed at major museums and influential galleries and nonprofits around the world, participating in just about every major recurring exhibition, including the Whitney Biennial and Istanbul Biennial in 1995, and three more Venice Biennales (in 1984, 2003 and 2013). His text interventions are on public display in cities and institutions the world over. In recent years he remained prolific; in 2021, his work has been included in five group exhibitions and he had solo shows with Galerie Thomas Schulte in Berlin and at the Holstebro Kunstmuseum in Denmark.

“All I’m interested in is working at this point because that gives me a great deal of satisfaction,” Weiner said in the 2019 AAA interview. “So if I can just keep working it will give me enough oomph to keep going.”