Neapolitan crèche (18th century); Colnaghi, London, during London Art Week Winter, 3-10 December; price: seven-figure sum

Now for something a little festive: this huge, 18th-century Neapolitan crèche (or presepe, in Italian) is a typically Baroque version of a Nativity scene. It is unusual to find these crèches outside of Naples, and this example (measuring 3.4m by 4.4m) is made from painted wood, terracotta, glass, shaped wire, tin, cork and fragments of silk and linen. Traditional Nativity scene figures, such as the holy family, wise men, angels and shepherds, are mixed with bawdier contemporary Neopolitan types, and so the Virgin Mary and infant Christ are surrounded by a rowdy procession of musicians and revellers who appear to have tumbled out of the tavern. Such elaborate creations were a common sight in Neapolitan churches by the 18th century.

Courtesy of Christie's

John Constable, Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Grounds (1823); Old Masters evening sale, Christie’s, London, 7 December; estimate: £2m-£3m

This oil sketch of Salisbury Cathedral by John Constable was known as “The Vision” by the artist’s family, which owned it until the end of the 19th century. The fluid sketch is the last known version of this view of the cathedral by Constable left in private hands and will now be offered at auction for the first time, consigned by a UK-based private collector. The 65cm by 76cm full-scale sketch is for a finished painting that is now in the Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California. It was commissioned by Constable’s most significant patron, John Fisher (1748-1825), Bishop of Salisbury, for whom Constable painted a famous series of works in the 1820s. The bishop’s daughter requested a copy of an earlier version of this view but, says Clementine Sinclair, the head of the Old Masters evening sale at Christie’s London, “Constable being Constable doesn’t just do a slavish copy; he actually wants to improve on his initial exhibition painting. So he executes this as a full scale compositional sketch.”

Courtesy of Sotheby's

The Penny Black, the world’s first postage stamp (1840); Treasures, Sotheby’s, London, 7 December; estimate: £4m-£6m

This is a pristine example of the very first postage stamp, the “Penny Black”, which enabled people to send a letter for, unsurprisingly, a penny. It may not seem revolutionary now but, prior to 1840, sending a letter was a rather complex process, with the recipient responsible for paying postage. Then the UK government held a competition to determine the best way to prove a sender had paid and the Penny Black, with a profile portrait of the young Queen Victoria on the front and a revolutionary adhesive gum on the back, was born. This, says Henry House, the head of Sotheby’s Treasures sale, is “the precursor to all stamps, and unequivocally the most important piece of philatelic history to exist; this is the stamp that started the postage system as we know it”.

Courtesy of Ketterer Kunst

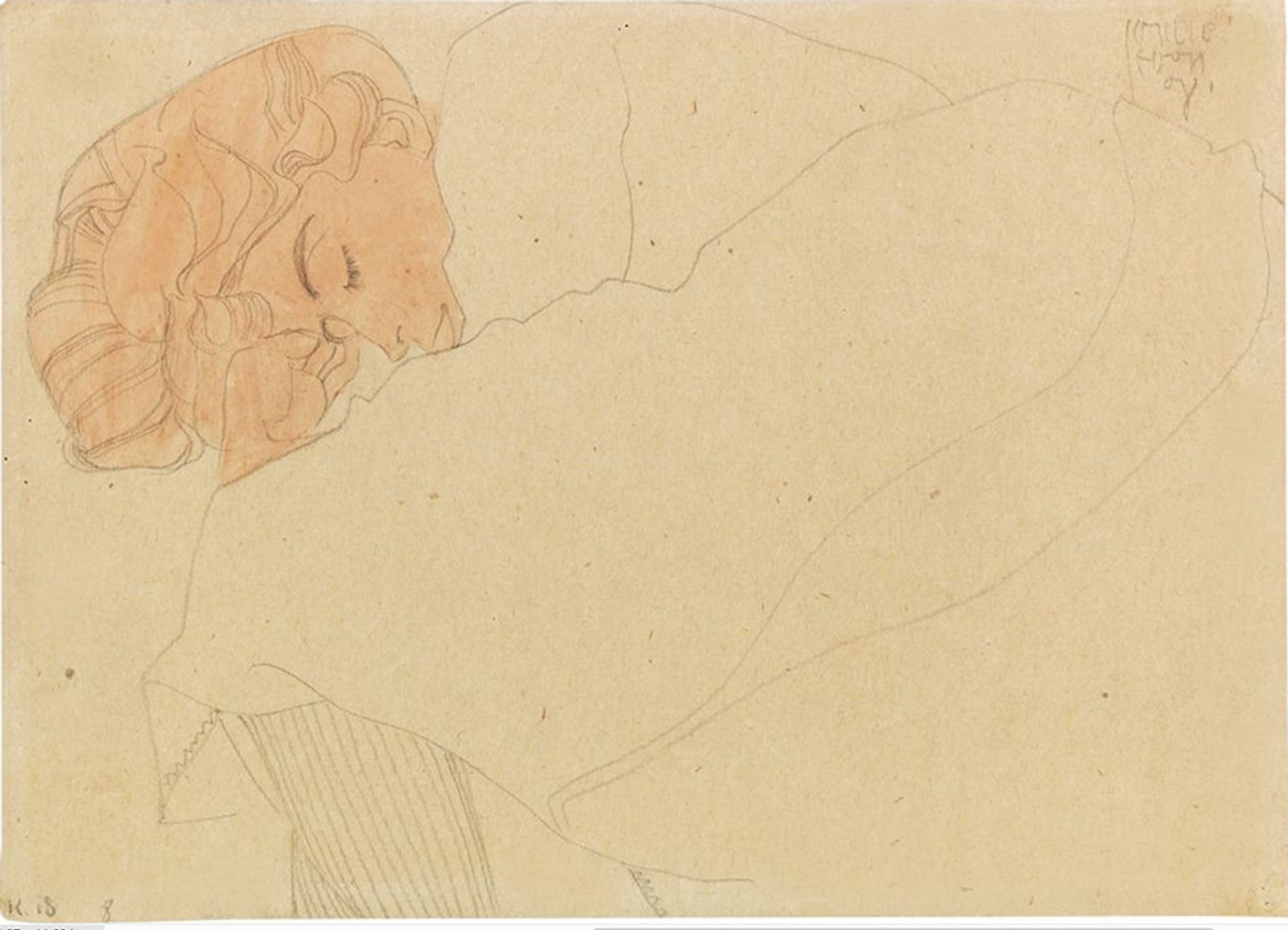

Egon Schiele, Schlafendes Mädchen (sleeping girl, 1908); Modern art evening sale, Ketterer Kunst, Munich, 10 December; estimate: €150,000-€250,000

Egon Schiele was 18 when he executed this small, serene pencil-and-watercolour-on-paper in 1908, one year after he dropped out of the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and sought the mentorship of Gustav Klimt. For the past 45 years, the work has been in a private German collection, unseen by the public. Inscribed “Besitz Hayd” (ownership Hayd) on its reverse side, it first belonged to the Austrian artist Karl Hayd with whom Schiele exchanged many of his drawings. From Hayd, it made its way into the collection of the American banker Joseph Drexel, although how this happened is unclear as, according to the Schiele expert and dealer Jane Kallir, there was no link between Drexel and either of the artists. Schlafendes Mädchen will be included in Kallir’s forthcoming catalogue raisonné on the artist.