In a career spanning 65 years, Patrick Reyntiens became one of the most influential and innovative figures in the world of stained glass, bringing a painterly fluency and wit to what is a time-consuming medium. Not only is it often constrained by its architectural (and ecclesiastical) setting, it is rooted in a challenging combination of craft disciplines: sourcing glass of different colours; baking stains onto glass in a kiln; cutting; painting with black lead or enamels; etching to refine details of expression; composing the glass into a design joined together with lead strips and sealed with putty to make a weatherproof finished article. “You have to accommodate yourself to a certain discipline and obedience,” Reyntiens wrote of stained-glass work, “before you can command the obedience of your material and your expressiveness... You learn things like patience. And yet you learn how to do things very quickly.”

[John] Piper, who had been copying stained-glass panels since his early 20s, understood the medium to a teePatrick Reyntiens

Reyntiens was an innovator who drew on his knowledge of the long history of stained glass and on the work of his great boundary-breaking predecessors including the Americans John La Farge (1835-1910) and Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933) and the Irish master Evie Hone (1894-1955). Hone’s East Window at Eton College Chapel, in Berkshire, caused a sensation at its unveiling in May 1952, when Reyntiens was taking his first steps in stained glass, for its powerful combination of colour, design, drawing and religious feeling. Reyntiens saw that window as marking the beginning of the co-operation between the eye of the craftsman and the eye of the artist in stained glass, a role that he took up in his own work and in his historic collaboration, between 1954 and 1984, with the artist John Piper.

The eye of the craftsman and the eye of the artist: Patrick Reyntiens's panel An Actor Dies (stained glass, 42.5cm x 52.5cm), 1990 Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

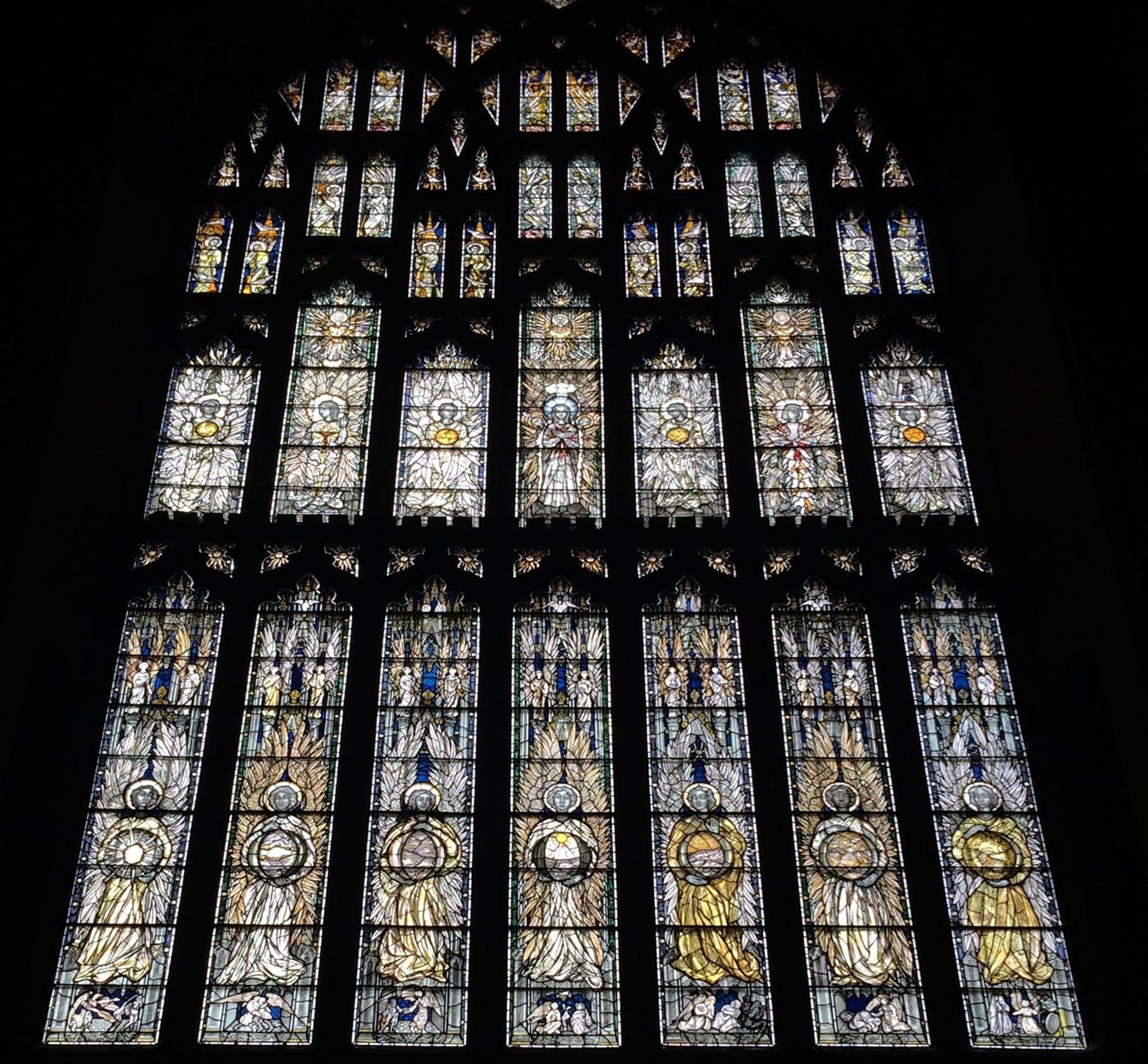

Patrick Reyntiens (designer and painter) and Keith Barley (glass maker), Angel Window (stained glass, 24.99m x 17.37m), Southwell Minster, Nottinghamshire, 1996 Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

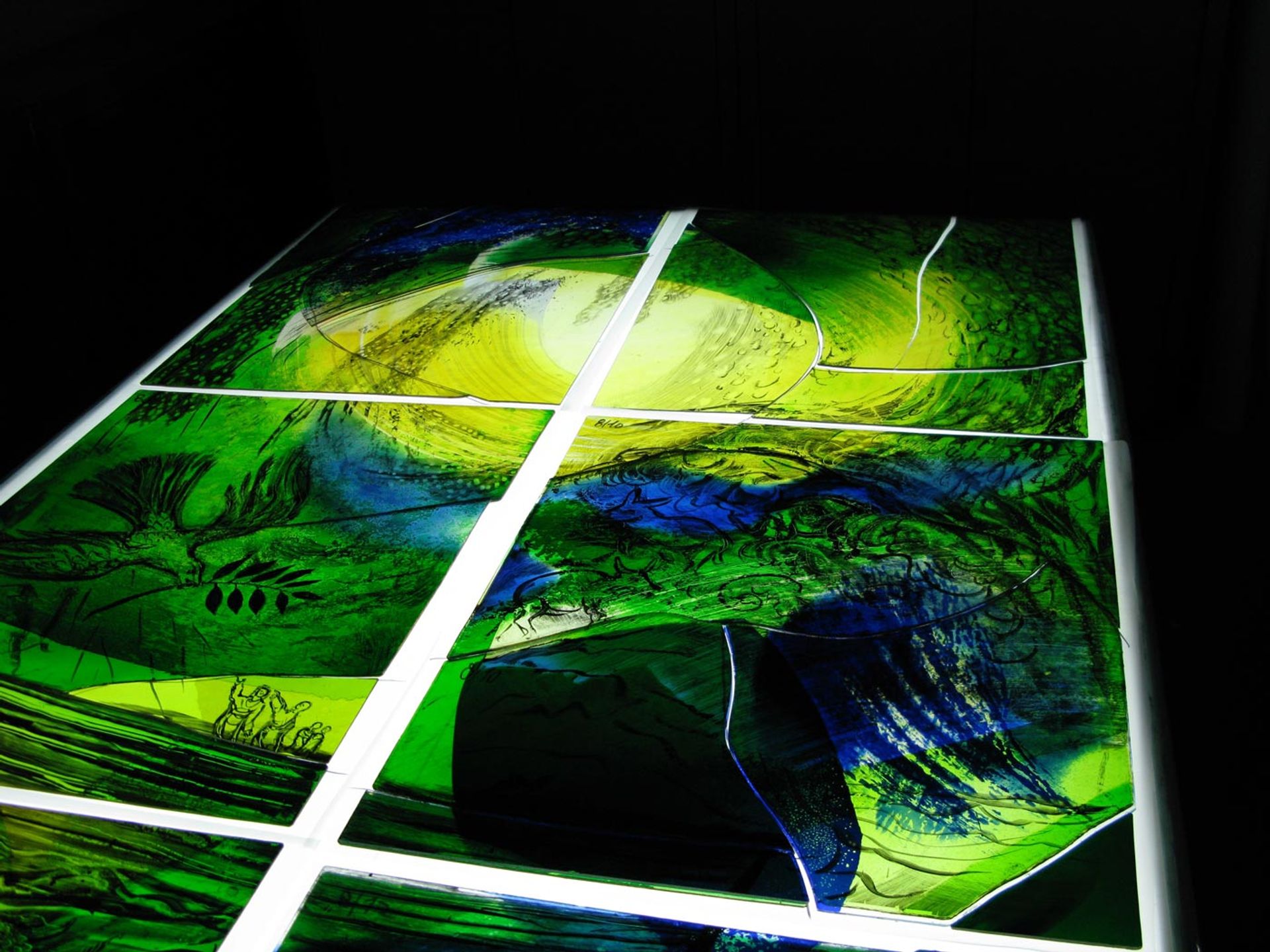

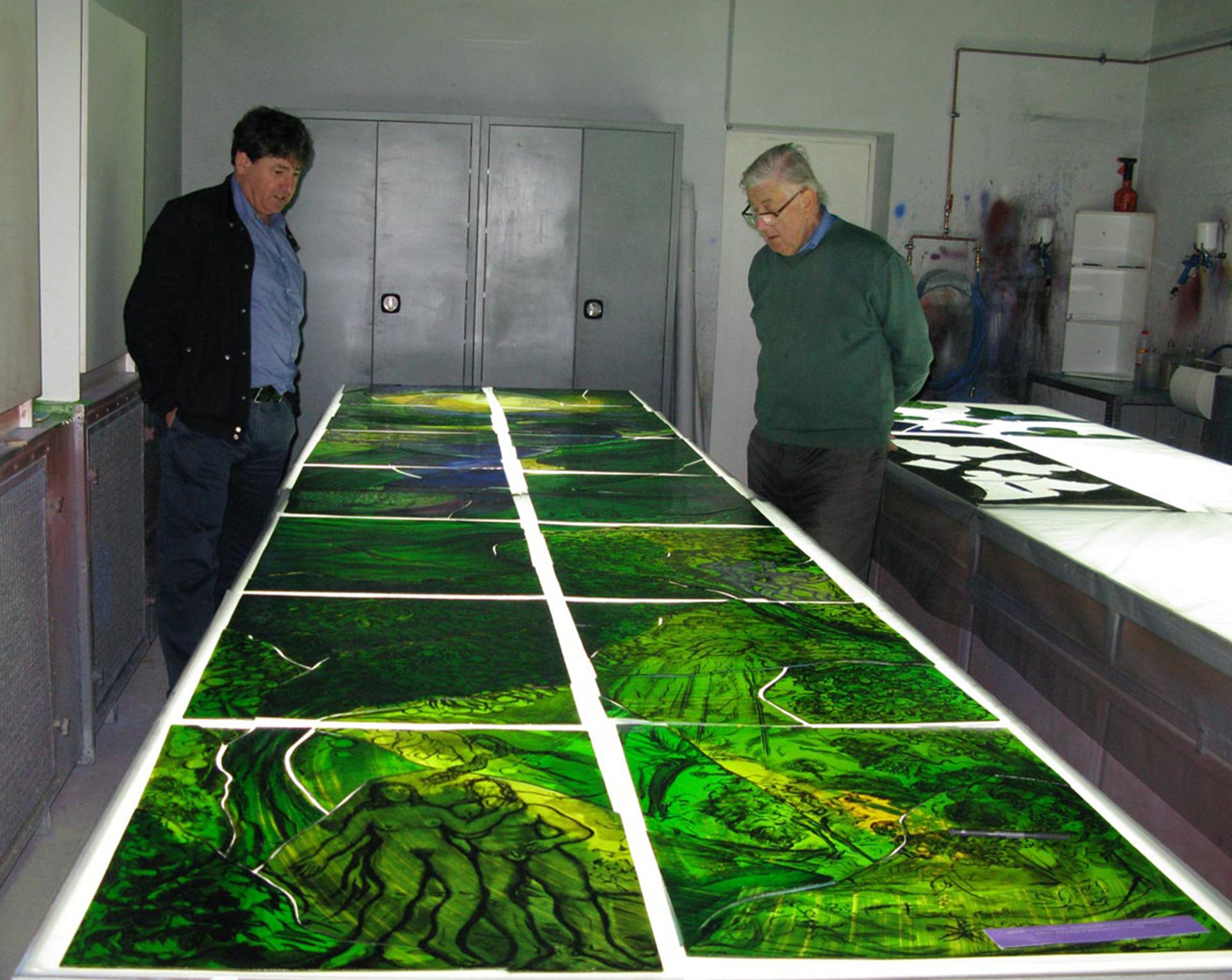

Pieces of painted glass assembled on glassbox for one of eight windows (each 12.19m tall) at St Martin, Cochem, Germany, 2009. Designed by Patrick Reyntiens and Graham Jones, painted by Reyntiens, with the glass made by Derix Studios, Taunusstein Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

Patrick Reyntiens, Hommage 1 (Hommage à Berlioz), (stained glass panel, 76.2cm x 111cm), 1986-88 Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

Reyntiens and Piper’s place as Hone’s successors, following her death in 1955, was reinforced by the commission they received to make eight windows (1959-64), each representing a parable, to flank Hone’s Eton masterpiece. “It was above all John Piper’s interest in stained glass, following on from the remarkable achievement of Evie Hone...” Reyntiens wrote in the Independent newspaper following Piper’s death in 1992, “that started the medium towards the sensibility of the painter, as it had been some 75 years previously with the new interest of Edward Burne-Jones and Henry Holiday... Piper, who had been copying stained-glass panels since his early 20s, understood the medium to a tee.”

Piper would conceive the designs, while Reyntiens made the glass. Working with a first-rate artist, Reyntiens said, encouraged him to “reinvent the technicalia of the art form”. Their headline commissions were for two of the great church projects in mid-20th-century Britain: the Baptistry window (1957-61), for Basil Spence’s rebuilding of Coventry Cathedral, which made Reyntiens, then in his early 30s, famous overnight; and the glass (1964-67) for Frederick Gibberd’s Metropolitan Cathedral in Liverpool—for the nave and side chapels, and, soaring above them, the 16 sections of coloured glass. Each 24m tall by 3.5m wide, they make up the central conical tower over the high altar, weighing more than 500 tons.

Piper’s preference, Reyntiens wrote, was for the smaller windows in the numerous parish churches that they worked on—about 35 in all between 1954 and 1984. Reyntiens thought Piper’s greatest design, in their three decades of collaboration, was for the two windows, Light of the World—Piper described it as “a great circulating light penetrating and dominating all nature”—and Epiphany (1979-80), both for the chapel at Robinson College, Cambridge. The columnist Simon Jenkins, author of England’s Thousand Best Churches (2000), described the memorial window they made for the composer Benjamin Britten, at St Peter and St Paul, Aldeburgh, in 1979-80, as their masterpiece. They also made a series of autonomous stained-glass panels, one of the earliest of which, an abstract experiment from about 1956, is in the collection of the Stained Glass Museum at Ely Cathedral. But, for Reyntiens, having the vast canvases of Coventry and Liverpool to work on so early in his career seems to have allowed him to develop a breadth of vision and fluency in execution that brought a thrilling freedom to his work.

Conversational powers

Reyntiens’ facility with a paint brush found a match in his conversational powers. He was clear in thought, trenchant in argument, and smooth in enunciation. His slow, amused drawl was a legacy of his pre-war, cosmopolitan, upper-class upbringing in London, Brussels and Scotland. But it was saved from affectation by his sense of humour, his actor’s sense of energy and instinct for a punchline, and his willingness to tell stories against himself.

Patrick Reyntiens, Circus 2 (71.1cm x 71.1cm), 1990 Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

He had an aura, and presence. Like a sun. Everyone fell under his spell. He broadcast so much energyDanny Lane

When the artist Danny Lane arrived from New York in 1975, at the age of 20, to study stained glass at Burleighfield—the country house near High Wycombe, in Buckinghamshire where Reyntiens and his wife, the painter Anne Bruce, had set up an art school in the late 1960s—he was overwhelmed by his first encounter with a man who was to become a valued teacher and guide. Reyntiens, then nearly 50, strode in wearing a kilt in his ancestral MacRae tartan, mixed prodigious cocktails for his students—”mes enfants” as he habitually called them—and launched into a recital of the poetry of Robbie Burns before breaking down in tears, too moved to go on. “He had an aura, and presence,” Lane remembers. “Like a sun. Everyone fell under his spell. He broadcast so much energy.”

A critic’s credo

That performative confidence was carried into Reyntiens’s writing. He was a fine critic of art, architecture, literature and music, with a range of reference based on broad reading. He was a bibliophile and haunter of second-hand bookshops, with a library of more than 10,000 volumes and that enabled him to place works ancient and modern into the wider context of the Western European cultural tradition, and beyond. He was a cradle Catholic, at home with the iconography of his Church commissions, and for 65 years he was published regularly in the Catholic press in Britain, covering every aspect of contemporary art, for Blackfriars, for the Tablet and most recently for the Catholic Herald.

A fine critic of music: Reyntiens's Hommage 2 (Hommage à Tartini), 1987 Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

He also wrote for the architectural press—in another life, Reyntiens might have been an architect himself—and for Country Life magazine, where he had scope to address some of his art historical passions. In a review of Ronald Lightbown’s 1992 monograph of Piero della Francesca he wonders when considering the long-standing conundrum in interpreting Piero’s Flagellation of Christ, painted a few years after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453, ”why the idea has not been tested as to whether the Byzantine figure in the foreground is not Thomas Paleologus, the Despot of Morea, attending the congress of Mantua, imploring the Pope (Pius II). If so, the figure overseeing the Scourging of Christ could be his brother Demetrius who… married his daughter to the Sultan Mahomet”.

He saw his métier in the broadest political and cultural context, as an art form with a grand tradition, but one that needed daily reinvention

Reyntiens’s self-awareness as an artist, and the prism that this gave him for shedding light on the ambitions and achievements of his contemporaries, is part of his power as a critic, one that presents itself as a passionate empathy for the artistic process. He saw his métier in the broadest political and cultural context, as an art form with a grand tradition, but one that needed daily reinvention. And he captured that sentiment in his 1968 review for New Blackfriars of a book on the twelve stained-glass windows designed by Marc Chagall for the Synagogue of Hadassah University Hospital in Jerusalem, completed in 1962. “The art of Chagall is primarily a traditional art,” Reyntiens writes, “reconciling the remote past with the present. In his art, which transfixes and transfigures this remote truth by means of a modern vision, Chagall succeeds triumphantly in doing in glass what his forebears were inspired to do in the scriptures. It is in the particular Jewish tradition, and also in the great tradition of all religious art.”

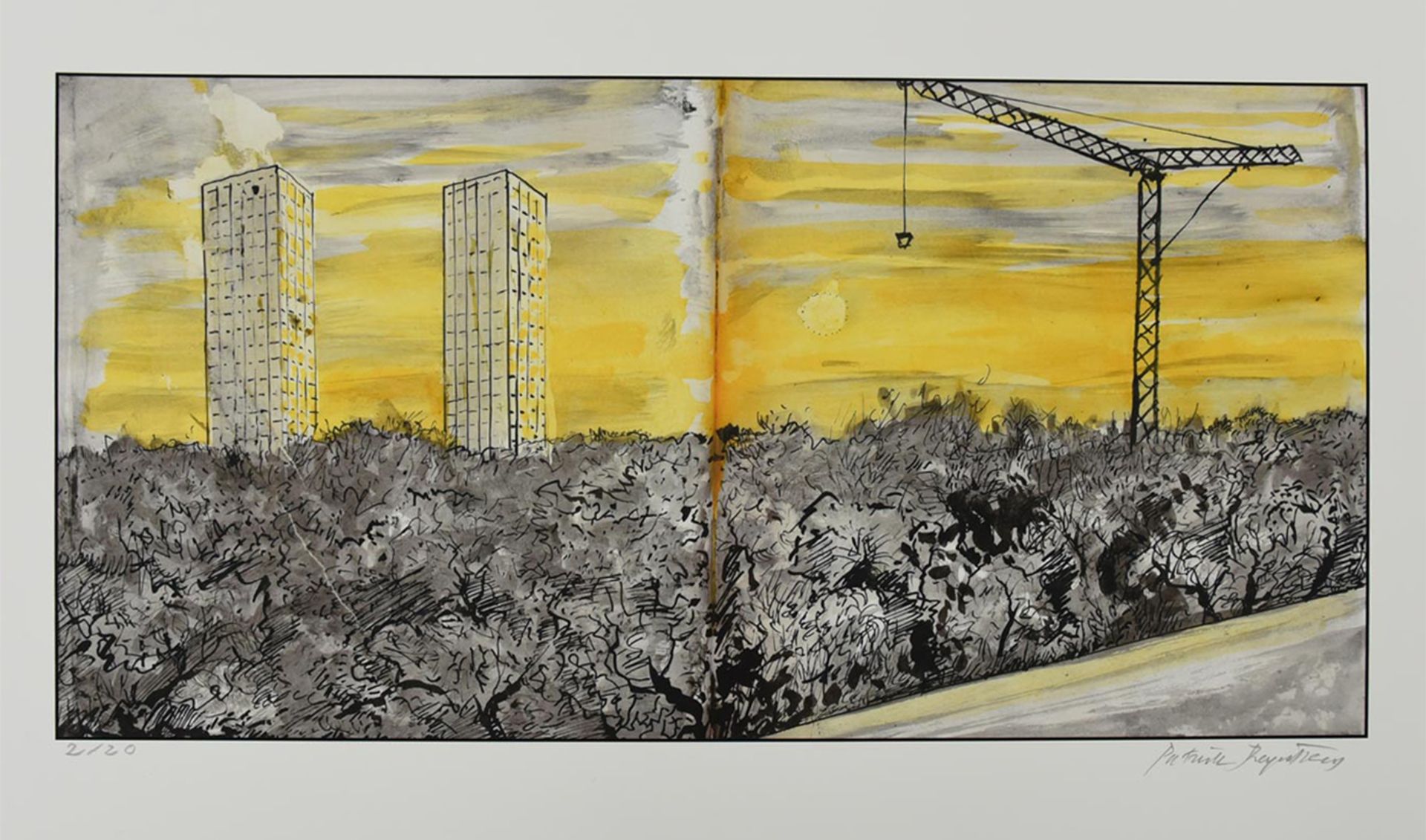

A love of architecture: Patrick Reyntiens, print from a sketchbook of the early 2000s Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

That transfixing and transfiguring of a remote truth by means of a modern vision feels central to the Reyntiens credo. He saw it just as strongly in the work of the visionary Welsh painter, poet and diviner of signs David Jones, who he so admired. He returned to the question in 1976 after seeing the new abbey church at Worth, near Crawley, in Sussex (1966-75), designed by his friend Francis Pollen. Reyntiens admired the building for having an “amalgam of implacability and delicacy” reminiscent of the Greek temples at Paestum and praised Pollen for producing “singlehanded a style that has reference to the past and can give hope for the future”. As ever seeing the artist in time and in the broadest cultural and historical context, Reyntiens addresses the question of legacy, telling Pollen that Worth “gives a subsequent architect, with the bravery to use it, a handle or lever to evolve a further step in the ladder”.

The handing down of his own legacy, as artist and teacher, is at the heart of Reyntiens’s books The Technique of Stained Glass (1967) and The Beauty of Stained Glass (1990), both of them readable and rich in historical context. Particularly memorable, in the latter, is his wide-ranging, international take on contemporary glass—including the work of the great German artists Georg Meistermann, Ludwig Schaffrath and Johannes Schreiter—his acute analysis of the development of the art form in France from the 12th to the 14th centuries, and his lyrical assessment of the subtlety of the 13th-century grisaille Five Sisters windows in York Minster that make almost no use of colour: “the most extraordinary phenomenon in glass to be seen anywhere”.

A cradle Catholic: Patrick Reyntiens (designer and glass painter), John Reyntiens (glass maker), Christ in Glory (13.72m x 7.72m), St George's Church, Taunton, Somerset, 2009-10 Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

A childhood in London, Brussels and Scotland

Reyntiens was born in London in 1925 at 63 Cadogan Square, Knightsbridge, the house of his paternal grandmother, Flora Reyntiens. The house’s entrance front was in a side street, facing east and, like some harbinger of Patrick’s future, filtering the morning light through windows rich in Arts and Crafts stained glass. Flora Reyntiens was a flamboyant Belgian socialite and talented amateur musician who had sat for John Singer Sargent and bought the artist’s house in Chelsea following his death. The family moved to Brussels in 1928 where Patrick’s half-Russian, half-Belgian father, Nicholas Reyntiens, was Britain’s commercial attaché. His mother, Janet MacRae-Gilstrap, was the daughter of John MacRae, a dashingly handsome colonel in the Royal Highland Regiment, idolised by the young Patrick, and of Isabella Gilstrap, heiress to a Nottinghamshire brewing fortune.

Nicholas and Janet Reyntiens lived a conventional life in Brussels, in a grand townhouse packed with family furniture, and looked after by eight servants. Life was formal. Young Patrick and his brother, Michael, had a regular routine culminating in an afternoon walk in the local park before their daily meeting with their parents at tea time—his mother he remembered as “very warm”, his father as “silent”, a “shadow” in his life—before being read to by their charismatic nanny, Violet Grey, who opened the world of the imagination to the young Patrick with her recitations of Jane Austen and Charles Dickens.

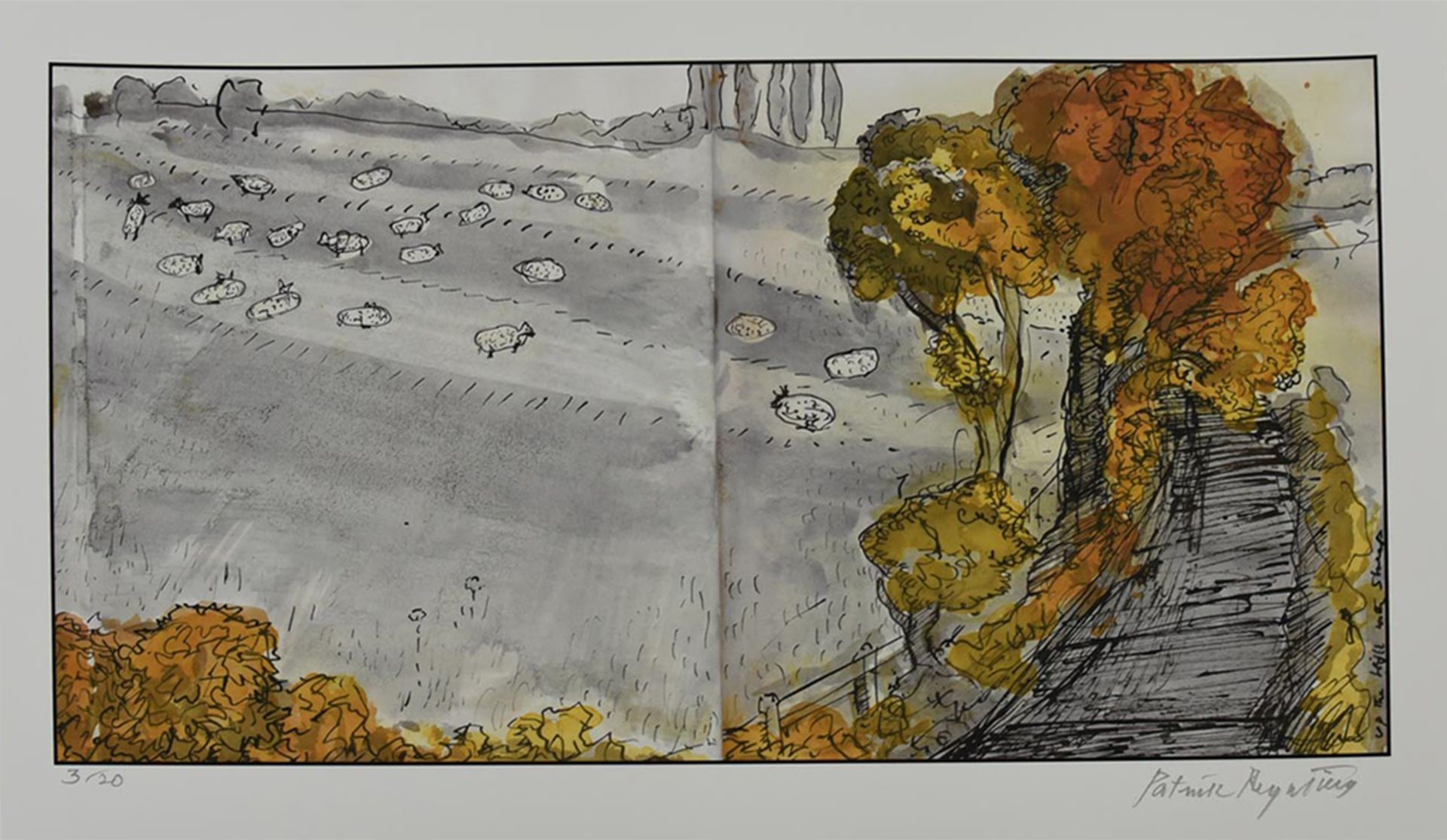

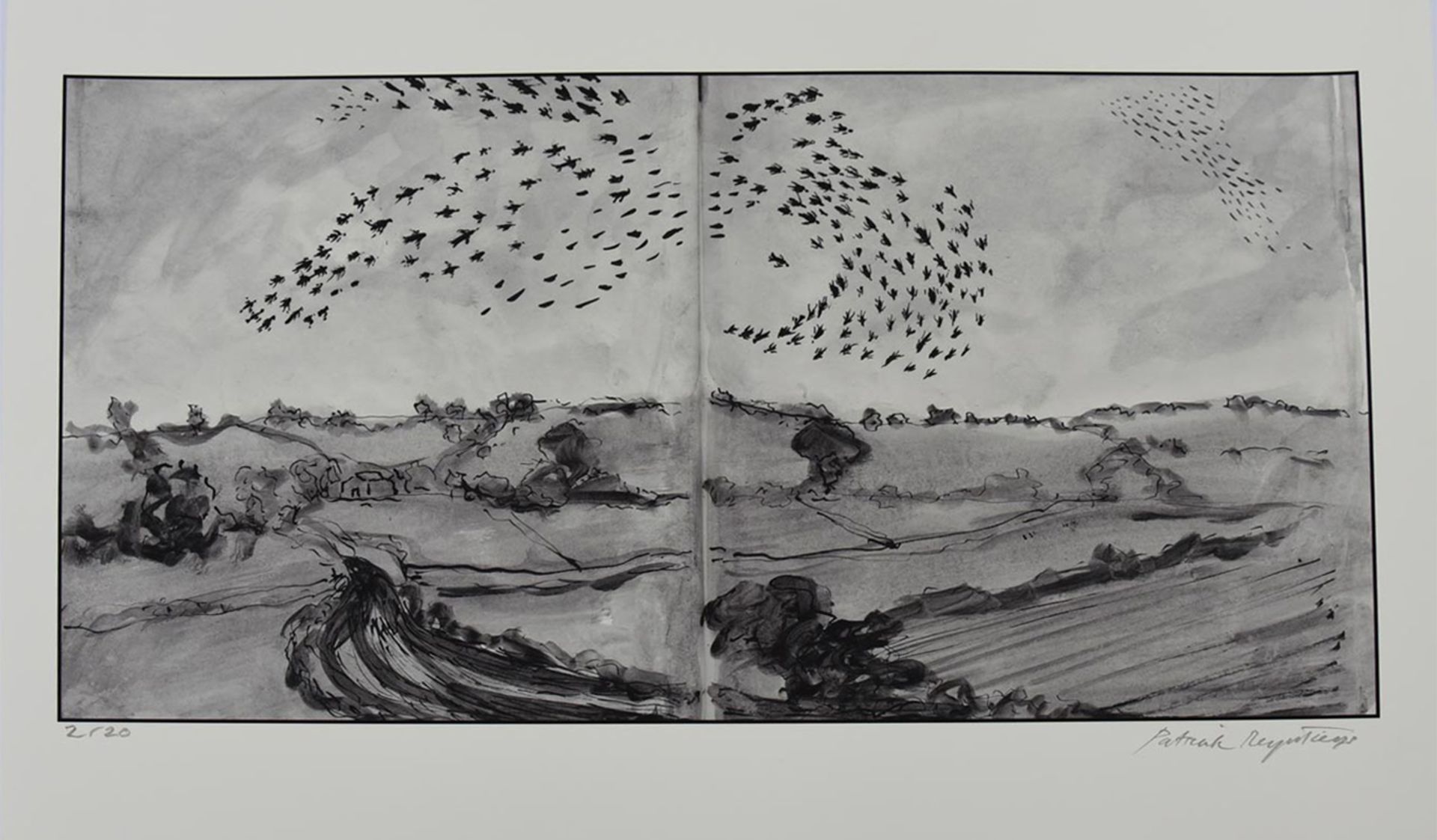

A love of the outdoors: Patrick Reyntiens, print from a sketchbook of the early 2000s Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

He was a good athlete and dancer and later enjoyed showing off prodigious leaps and bounds in the showiest of Scottish reels

The highlights of Patrick’s childhood were the thrilling annual summer trips to Scotland, filled with grand highland vistas and hearty outdoor pursuits—he was a good athlete and dancer and later enjoyed showing off prodigious leaps and bounds in the showiest of Scottish reels—where the MacRae-Gilstrap grandparents lived in baronial style at Ballimore House, in Argyllshire. They also bought and rebuilt, in 1912-32, the famously picturesque but long-ruined Eliean Donan, an island castle on Loch Duich, Ross-shire, and now a global symbol of Scottish heritage and tourism.

Reyntiens was sent to Avisford, a fashionable Catholic preparatory school near Arundel, in Sussex, and then to Ampleforth College, in Yorkshire, where he judged himself to have been very well taught by the Benedictine monks, where he enjoyed all games except cricket—potentially injurious to an artist’s hands—where art was strongly encouraged and where Dom James Forbes, a fellow Scot and the future master of St Benet’s Hall, Oxford, taught a class in Scottish dancing as an essential social skill.

Patrick Reyntiens (design and glass painting), John Reyntiens (glass making), Memorial windows, South Transept, Ampleforth Abbey, Yorkshire, 2002-03 Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

His parents moved back to Britain, to country life in Devon, in 1938, a year ahead of the outbreak of the Second World War. Reyntiens volunteered for the Scots Guards before his 18th birthday and was deployed to Germany soon after the end of hostilities. His regiment was subsequently sent to act as honour guard to Winston Churchill at the Potsdam peace conference with Joseph Stalin and Harry Truman. Reyntiens, with his eye for colour, was fascinated by Churchill’s complexion: “He had a face like sliced cooked ham. It was that particular pink.”

Reyntiens was then posted to Trieste, as an infantry officer in command of a mortar platoon for 18 months, at a time when the northeast of Italy felt exposed to the spread of Communism from neighbouring Yugoslavia. While in Trieste, he got to visit Venice on two occasions. In 1947 he was transferred to an army retreat centre outside Milan, which he administered, and then to another outside Padua, which looked out on to the hills that are the model for Virgil's Georgics, and where Reyntiens fell in love with Italy.

A love of drawing: Reyntiens at work on a panel in his studio, 2011

An art student in London and Edinburgh

Reyntiens had discovered a love of drawing at the age of five. His family was filled with enthusiastic artists—his mother painted watercolours; an aunt had been offered, but declined, lessons from the equestrian artist Alfred Munnings—and Reyntiens had painted an altar back for the Catholic chapel during his posting in Trieste. After leaving the army in 1947, he enrolled as an art student at Regent Street Polytechnic, in London, where he was impressed by the quality of teaching and grateful for the proximity of the latest contemporary art shows, before winning a scholarship in 1949 to the Edinburgh School of Art.

He... relished the quality of the teaching and the discipline of three-hour life classes, four evenings a week

In Edinburgh he found himself in happy proximity to swathes of Scottish cousins—his mother’s sister Lady Campbell of Arduaine had created a famous rhododendron garden at Arduaine, Argyllshire—and he again relished the quality of the teaching and the discipline of three-hour life classes, four evenings a week. He studied with William MacTaggart the Younger, who Reyntiens found a marvellous teacher of still life drawing, and who really taught him to look, and William Gillies. One of the models—“bored to a degree” according to Reyntiens—was the young Sean Connery, on the brink of his acting career.

Reyntiens saw drawing as a great aid to memory and, until the end of his life, could tap into the discipline of those Edinburgh life classes to draw a male or female nude from memory. During his army and student years he managed to see a remarkable amount of Western Europe—France, Italy, Spain and Portugal—given the restrictions on currency exchange and travel in the postwar era, being particularly struck by the beauty of the 16th-century stained glass in Segovia Cathedral during a trip to Spain in 1949.

Stained glass and married life

At Edinburgh, where Richard Demarco and Elizabeth Blackadder were contemporaries, Reyntiens got to know one of the star pupils, Anne Bruce (they had met briefly in London when Anne was studying at the Slade School). They broke the ice when he helped her to perfect a paper chicken outfit that she had devised for a college stage show. Towards the end of Reyntiens’s time at Edinburgh, in 1951, another of his fellow pupils, Patrick Nuttgens, who was studying art and architecture, said that his father, JE “Eddie” Nuttgens, was looking for an assistant at his stained-glass studio at North Dean, near High Wycombe, in Buckinghamshire. Reyntiens passed the test—six weeks of hard work applying putty to a new window for St Etheldreda’s, Ely Place, in London—and was hired, for £3 a week.

Country life: Patrick Reyntiens, print from a sketchbook of the early 2000s Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

Reyntiens and Anne Bruce were married in 1953 and set up home at Flackwell Heath, eight miles from North Dean. Bruce, a remarkable painter in her own right and the winner of a John Moores award in 1961—in company with David Hockney, Peter Blake, RJ Kitai et al—was, for 53 years of marriage and professional collaboration, the calm counter to the prodigious energy of her husband. Reyntiens felt that the fount of his formidable personal energy lay in the certainty he felt in his marriage and his religious faith and the challenge he felt in setting out daily to renew tradition in every piece of art that he made.

Reyntiens’s work for Eddie Nuttgens, whom he regarded as a saint, gave him the craft skills he needed to make stained-glass an art. His nascent career received a huge lift when the poet John Betjeman told him in 1954 that Piper—then at the height of his public fame following the success of his giant mural for the Festival of Britain in 1951, and a Buckinghamshire neighbour at Fawley Bottom—was looking for someone to realise his designs for three stained-glass windows for the chapel at Oundle School, in Northamptonshire. Reyntiens was bowled over by Piper’s cartoons for the project, and moved to reach for a musical metaphor: “What Stravinsky has done in relationship to music... these designs have accomplished in relationship to stained glass”. Piper and Reyntiens made a test panel for the client’s approval in June 1954, and the windows were completed by mid-1956, by which time Reyntiens had built his own studio and gone his own way, with Nuttgens’s blessing and support.

35 years’ work with John Piper

Reyntiens and Piper built up a profound mutual respect as collaborators, based, according to Reyntiens, on Piper’s personal kindness. After the consecration of Liverpool Cathedral in May 1967, Reyntiens wrote to Piper that he was “terribly proud to have done that tower and the rest of the cathedral with you. I hope you feel happy about the whole work, which considering the difficulties that had to be overcome, was a great success”.

When he worked with another artist as designer, Reyntiens was an historically informed interpreter and orchestrator of every aspect of the finished work

Piper, the senior in age and celebrity, welcomed Reyntiens’s input at every stage. When they were struggling to find a subject for the lantern glazing at Liverpool, Reyntiens suggested the last stanzas of Dante’s Paradiso, describing the Holy Trinity, represented by three great eyes of blue, yellow and red. Piper agreed with the suggestion but asked: “And did Dante tell you what to do with the rest of the cathedral?”

Reyntiens was nettled, in turn, when outsiders saw his role as that of a glorified technical assistant to Piper or to other artists such as Ceri Richards (for a 1960 panel, La Cathedrale Engloutie; and two windows for the Cathedral Church of All Saints, Derby, 1962) and Cecil Collins (for three Angel windows at All Saints, Basingstoke, 1985). The reality was that, when he worked with another artist as designer, Reyntiens was an historically informed interpreter and orchestrator of every aspect of the finished work.

A passionate empathy for the artistic process: Patrick Reyntiens, Death of Orpheus (stained glass panel, 91cm x 71.1cm), 1984 Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

His sense of the imaginative agency of the glassmaker in any collaboration is reflected in a comment he makes In The Technique of Stained Glass. “It is a mistake to think that the most important stage of the making of a stained glass window is in the cartoon...” he writes. “I feel it is better to have a defective cartoon that leaves some leeway for spontaneity and imagination in the executing of the idea in glass, than to have a perfect cartoon rather pedestrianly and mechanically copied into glass.”

Piper’s designs were made with all the freedom and franchise of a painter and I had to take them into my very spleen and liver and re-interpret themPatrick Reyntiens

On the 30th anniversary of the Coventry window, Piper gave most of the credit for its success to Reyntiens “the craftsman and scholar”. Reyntiens referred to their collaboration in visceral terms. “Piper’s designs were made with all the freedom and franchise of a painter and I had to take them into my very spleen and liver and re-interpret them,” he told the art historian Tanya Harrod in 1993, “very much as Rimsky Korsakov re-orchestrated Mussorgsky. And that to me is not an illicit occupation.”

Reyntiens the autonomous artist

Given the importance of Reyntiens’s collaboration with Piper in the first half of his career, it is easy to overlook just how productive he was in his own right from the late 1950s onwards. Reyntiens created 50 large projects under his own name, as well as 150 or so autonomous panels and 300 small studio panels.

His first solo Church commissions were for St Leonard’s, St Leonards-on-Sea, Sussex (Old and New Testament Characters, 1957), and St Mary’s, Hound, in Hampshire (Virgin and Child, 1958-59), which Reyntiens considered one of his finest accomplishments. Reyntiens had some Coventry-related stained-glass in the group show British Artist Craftsmen. An Exhibition of Contemporary Work, which opened at the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington DC, in January 1959 and toured the US for the succeeding two years. His fellow exhibitors, besides Piper, included Graham Sutherland, Jacob Epstein, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Elizabeth Frink, Reg Butler, Hans Coper and Lucie Rie.

Patrick Reyntiens, Hommage à Wagner (Landscape 'Into Winter'), (stained glass panel, 94cm x 45.7cm), undated Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

Reyntiens creates a film that seems to separate you from the outside world: it is a liberation which enables you to see everything—and nothingIlltud Evans, 1961

In 1961, the year of the unveiling of the Baptistry window at Coventry Cathedral, Reyntiens had his first solo London show of studio panels—”abstract and decorative”—at the Jeffress Gallery in Mayfair. Illtud Evans, reviewing the show for Blackfriars, praised the handling of the glass, the ”brilliant experiments in conveying texture and subtle shifts in the levels of opacity”, and felt Reyntiens, ten years after his first work with Nuttgens, had liberated himself from the visually limiting effects of leading in stained glass:

“Mr Reyntiens creates a film that seems to separate you from the outside world: it is a liberation which enables you to see everything—and nothing. Thus the leading, which so often interrupts the harmony of a window and imposes arbitrary restrictions of design, is somehow transcended. In a panel called Caesura, the left side is a series of lateral lights, grey and white, balanced by brilliant blocks of orange and green on the right. The effect is wonderfully rhythmical, and it could not possibly have been achieved in any other way.”

He made a window of the Annunciation for the abbey church at his old school, Ampleforth, in 1961. “I thought the Annunciation was supposed to be good news!” remarked the abbot, Herbert Byrne, regarding the figure of Our Lady—modelled on Anne Bruce and described by Nikolaus Pevsner as “Expressionistic”. Reyntiens created some of his most successful abstract designs in floor-to-ceiling panels for two large new Catholic churches in Co Waterford, Ireland, in the late 1960s.

There were also two solo windows for the National Episcopalian Cathedral, in Washington DC (1962-69) and (1970-75) and one collaboration there with Piper for a Winston Churchill memorial window (1972-74). Another Ampleforth-related commission, to glaze a large new church at Leyland, in Lancashire (1963-64), used blocks of colour in 3cm-thick dalle de verre—literally “slabs of glass”—made up into a series of large panels. This project inspired the materials and method of assembly for the lantern work at Liverpool Cathedral. In the mid-1960s Reyntiens might often have had five projects of his own on the books at any time, as well as four or five collaborative commissions with Piper.

Breadth of range: Patrick Reyntiens, detail of a window at St Duthac's Church, Dornie, Kyle of Lochalsh, 1970s Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

Cathedral scale

The Reyntiens family moved to Burleighfield in 1961, by then with the addition of the three eldest of their four children. For the Liverpool work in 1964-67, the cathedral’s main contractors, Taylor Woodrow, built a new studio at Burleighfield, with production organised to the minute by the 25-year-old technical supervisor David Kirby. Reyntiens would get up at 4am to work with the latest cartoons, sent over from Piper’s studio in Fawley Bottom, to plot the placing of the dalle de verre blocks used for the project. Then the cartoons were transferred for the cutting of the glass by a team of four technicians, and the panels assembled and cemented on specially made tables.

Reyntiens was amused when the besuited engineer who had received the test samples in silence for nine months, perked up on the last day saying 'I love concrete. I could eat it'

New techniques had been devised, to assemble the panels, using long threads of glassfibre as reinforcement, set into an epoxy-based cement. Every mix of this innovative concrete had to be sent to London to be tested, to make sure the recipe was correct. Reyntiens was amused when the besuited engineer who had received the test samples in silence for nine months, perked up on the last day saying “I love concrete. I could eat it.”

The process was captured in a documentary, A Crown of Thorns (1967), made by the Shell Guide film unit. In one scene, Piper and Reyntiens are seen holding glass samples up to the sun, in another both draw at once, with darting strokes, on a sketch of the cathedral. In another sequence they are both in socks but no shoes, painting the cartoons on the floor of Piper’s studio with the broadest of decorators’ brushes. Reyntiens consults with a group of engineers, pouring the coffee, and he is seen at work with glaziers, foreman and forklift truck drivers at Burleighfield. There is a sense of a project in perpetual motion. They assembled 250 panels in all. At the height of production, three two-ton panels left the studio every night at 11pm and were transported to Liverpool to be on site and hoisted into place the following morning.

Burleighfield as an art centre

With the cathedral projects coming to an end, and needing a use for the campus of buildings at Burleighfield, Patrick and Anne set up a school in 1968, and started to hold exhibitions, indoor and out. They advertised internationally—Reyntiens’s The Technique of Stained Glass had been published in 1967 (one US book club alone shifted 10,000 copies)—and took in students from around the world. The school offered a broad range of subjects beyond painting and drawing, including stained glass, pottery, tapestry and history of art. The glass students had the chance to apprentice and help on occasion in the studio—where considerable projects were being worked on.

In the summer, six or seven students would join trips through France in the family Volkswagen camper van. Reyntiens waxed lyrical as he drove, Danny Lane remembers, using his encyclopaedic knowledge to put towns, buildings and historical personalities into instant context. They went to the great medieval cathedrals of Rouen, Poitiers, Chartres, Albi and beyond; to Matisse's chapel at Vence, the Fernand Léger museum at Biot, the Chagall museum in Nice. And the great châteaux of the Loire valley. “He might have been one of the greatest scholars,” Lane says, “of historical stained glass in Europe”. At the same time Anne Bruce was taking a lead role at the school, running a large painting class, children’s classes, and a course, with an on-site crèche, designed specifically for mothers with small children.

The economics of a stained glass studio were hard to manage without large-scale projects. It was, as Reyntiens put it, 'flush or bust'

Burleighfield hosted a big stained-glass show and, following the example of the London County Council open-air exhibitions in Battersea Park and Holland Park, they held sculpture shows—the young Phillip King and Barry Flanagan were among the artists—with rides cut through the Victorian wilderness garden at Burleighfield to give each piece “its own authority”. Preparing the garden for the shows, Reyntiens was reminded of his pre-war gardening aunts and grandparents in Scotland. It was an approach—Frederick Laws of the Times admired a 1968 show that he found “enclosed and theatrical”—that was later taken up at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Dean College in Sussex, and Madeleine Bessborough’s New Art Centre at Roche Court, near Salisbury.

Patrick Reyntiens, Trippin' the Boards (stained glass panel, 42.5cm x 34.3cm), 1986-90 Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

Ten years at Central

The economics of a stained glass studio were hard to manage without large-scale projects. It was, as Reyntiens put it, ”flush or bust”, either too much or too little work, sometimes with nine months or so between projects, but always with a studio building to maintain and glaziers and other technicians to pay. In 1976, Reyntiens took a job at Central School in London, where he was the head of fine art until 1986, and summer school work in the US. The family was forced to give up Burleighfield in 1976. Reyntiens set up a new studio nearby, in a rented school building in Beaconsfield, and the family moved to Ilminster, in Somerset, in 1980.

In his ten years at Central, where he had remarkable tutors such as the mystic Cecil Collins, the sculptor Bill Turnbull and star stained-glass artists from Germany and beyond, Reyntiens tried to recreate the holistic atmosphere of Burleighfield, one that allowed students to challenge themselves and discover their core enthusiasms. Students might be invited to lunch—cooked by Reyntiens on the grill in the etching room—and sat next to an imposing guest, such as Reyntiens’s cousin Peregrine Worsthorne, the columnist and editor of the Sunday Telegraph. Reyntiens was distressed at the merger of Central with St Martin’s College—he saw the values of the two colleges as incompatible—and fought to retain life classes and the core teaching that had given him the tools to forge his own career.

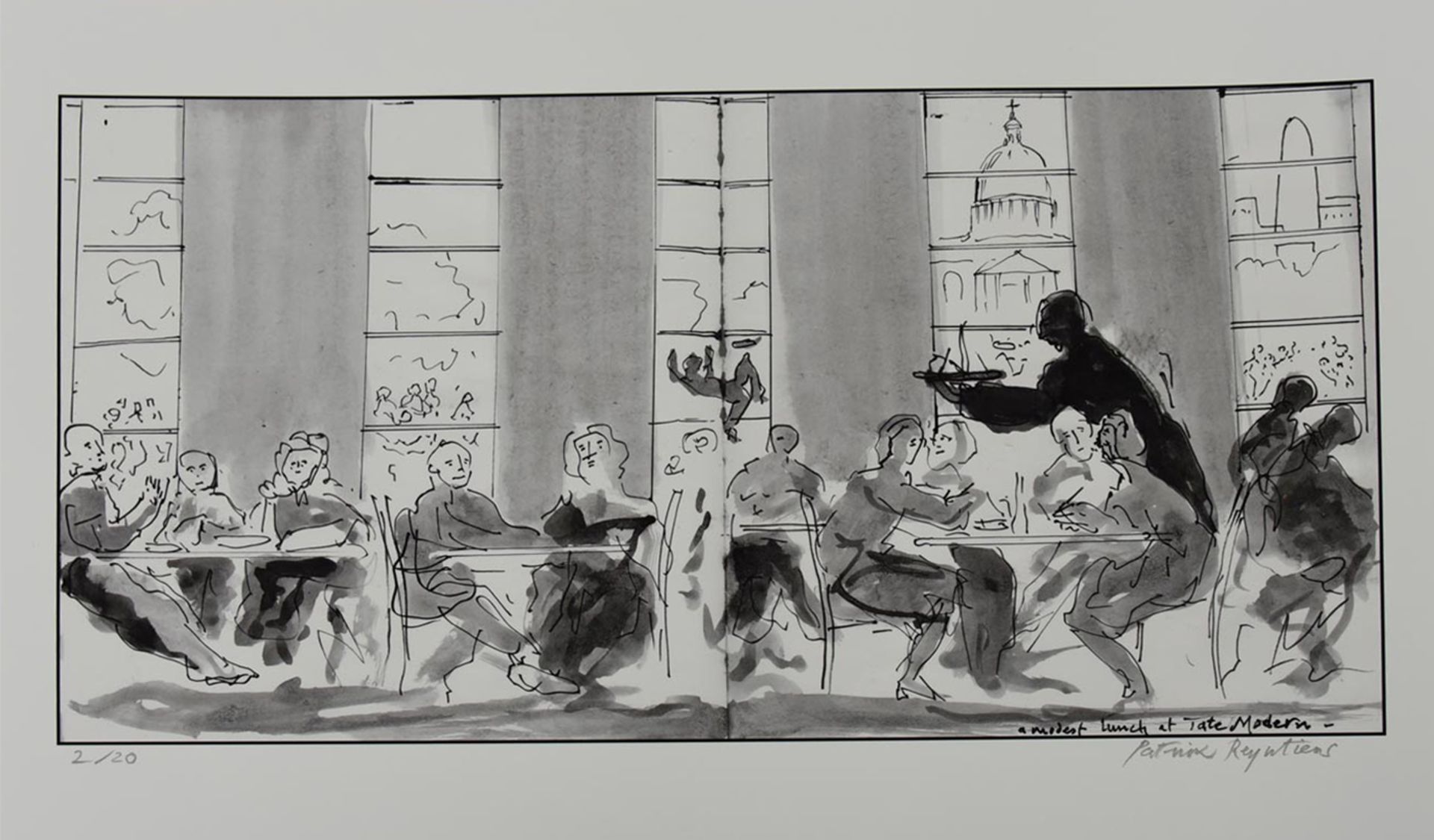

Patrick Reyntiens, A Modest Lunch at Tate Modern, print from a sketchbook of early 2000s Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

While running his busy department at Central, and contending with the upheaval and distress of moving house and studio, Reyntiens was producing some of the finest glass of his career. Two contrasting commissions, both completed in 1984. show the breadth of his range.

In the 14 windows of The Stations of the Cross at St John Fisher, Merton, south-west London, the style is bold, graphic: Christ in white, his tormentors in scarlet. In the Great Hall at Christ Church, Oxford, the remit was very different: to create new windows—as memorials to leading figures in the history of the college—to complement the existing 19th-century stained glass windows in a Tudor great hall. The solution, executed in a half-Gothic, half-Baroque style from 1588, as if, as Reyntiens put it, the Reformation had never happened, works to a nicety, with a refined palette and exquisite handling of detail, without ever collapsing into pastiche.

'Very fine', Piper said to Reyntiens, his old collaborator—a compliment exquisite in its brevity

Those long familiar with Reyntiens’s work were impressed at this fresh side to his art: a testament to his deep knowledge of the history of stained glass and the abiding sense he had for rhythm, for subtle variation in composition between a series of apparently similar windows, and for how elegantly each is bordered to mark the transition between glass and its architectural housing. There was a huge party to mark the completion of the work, hosted by the Dean of Christ Church, Eric Heaton, who had pushed the project through, while keeping the detailed demands of students and college fellows in orderly check. “Very fine,” Piper said to Reyntiens, his old collaborator—a compliment exquisite in its brevity.

Patrick Reyntiens, Circus 4 (stained glass panel, 71.1cm x 71.1cm), 1990 Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

Patrick Reyntiens, Circus 5 (stained glass panel, 71.1cm x 71.1cm), 1990 Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

The mature studio panels

With retirement from Central in 1986, Reyntiens focused anew on autonomous panels, “emancipated from the thrall of modern architecture”, drawing on his large stock of glass offcuts to make pieces that might be sold in galleries and editions. These panels—on the theatre, the Orpheus legend, and hommages to his favourite composers—have a remarkable fluency and painterly impact. The 1990 Circus panels have a haunting quality all of their own, bringing to glass the fluency of a Rowlandson ink caricature and the graphic energy of a William Nicholson lithograph.

'The beauty is,' [Graham] Jones remarked after the dedication, 'the figures don’t match the colour, that’s where the mysticism is'

In 2011, Libby Horner published an article on “Patrick Reyntiens’ autonomous panels: myth, music and theatre” in the Journal of the Decorative Arts Society. She traces Reyntiens’s skill in “allowing his figures to float across the leading and colouring” to his 1959 east window for St Mary's in Hound, Hampshire, and saw that skill’s apotheosis half a century on, in the eight windows for St Martin's in Cochem, near Frankfurt (2004-09).

Reyntiens, then in his early 80s, collaborated on the design with a younger artist, the brilliant colourist Graham Jones, but painted all the glass himself—in socks, shorts and T-shirt—at the famous Derix studios in Taunusstein, near Wiesbaden, with leading lines so fine as to be almost invisible. “The beauty is the figures don’t match the colour, that’s where the mysticism is,” Jones remarked after the dedication.

Graham Jones and Patrick Reyntiens contemplate Prehistory, one of the eight windows they designed for St Martin's, Cochem, Germany, 2004-09 Courtesy of John Reyntiens

A family collaboration

Reyntiens was able to take on large commissions late into his 90s, still handling the design and painting, thanks to a collaboration with his stained-glass artist youngest son, John. Their first project together was a window at St Andrew in Much Hadham, Hertfordshire, in 1994-95—making use of an etching provided for the purpose by Henry Moore, Trees V: Spreading branches (1979) made before his death in 1986. They created a dozen projects in all in the succeeding 20 years.

Brilliant, quirky, opinionated but hugely informed and loveableRoy Strong on Patrick Reyntiens

The projects in which John Reyntiens translated his father’s designs and painted glass into windows included three sets of windows for Ampleforth Abbey (2002-03, 2003-04 and 2006-07) and the West window at St George’s in Taunton, Somerset (2009). One of Patrick Reyntiens’s largest late commissions was for the great West window at Southwell Minster, Nottinghamshire (1996), where he created the cartoons—for a glazed area 24m by 17m—at a rented hall near his house in Somerset, before going to Keith Barley’s studio in York, to paint the glass. Barley was astonished when the 70-year-old Reyntiens said that he would complete the work—which Barley thought might take six months—in six weeks.

Patrick Reyntiens (designer and glass painter), John Reyntiens (glass maker), Tree of Life (stained glass), St Andrew, Much Hadham, Hertfordshire, 1994-95. The lower section of the window makes use of an etching provided for the purpose by Henry Moore, Trees V: Spreading branches (1979), before his death in 1986 Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

Captured for posterity

The purple Reyntiens voice and slivers of his encyclopaedic knowledge were captured raw and unedited, shortly before his 80th birthday in recordings he made for the National Life Stories Collection of the British Library. The recordings catch the Reyntiens who Roy Strong, writing a preface to the 2013 catalogue raisonné of Reyntiens’s work, describes as “brilliant, quirky, opinionated but hugely informed and loveable”. In that catalogue, written and edited in exemplary style by Libby Horner, you hear Reyntiens the anecdotalist in some of the entries, but Horner takes pains to include the voices of others: architects, collaborating artists, glaziers and other technicians.

One of Reyntiens’s favourite stories related to how he and Piper had devised the design for the Baptistry window at Coventry. The structure was already built before they started, as a “nutmeg grater” of alternating openings (150 in all) and concrete blocks. Any design made to work in a single opening would be too small to “tell” in the cathedral. Piper was at a loss. Reyntiens had been reading a book on Bernini and had been struck by the solution Bernini used in the apse of St Peter’s Basilica, in Rome—an extravagant sunburst in plaster—to visually pull together the mass of columns and pilasters. He suggested to Piper that they needed an equivalent explosion of colour across the busy mass of small openings to make the Coventry window work. Piper agreed. Horner published this story but points out that the architect Basil Spence later claimed that it was he who “encouraged [Piper] to do a burst of light symbolising the giving of life and strength to the green and red below”. “The truth”, Horner writes, “probably lies somewhere between these conflicting claims.”

Horner had previously made, with Charles Mapleston, a documentary on Reyntiens—From Coventry to Cochem (2010)—commissioned by John Reyntiens. The documentary includes interviews with Sir Roy Strong, Richard Demarco, and former students including Danny Lane and Ray King. One of the scenes has Reyntiens visiting the large secular window he made with Piper in 1959-60 for the fabric and wallpaper makers Sanderson, who wanted something really imposing for their London showroom in Berners Street, Fitzrovia (now the Sanderson London hotel). “Piper was very interested in fireworks,” Reyntiens says, “and had an amazing command of colours that suddenly burst on to your vision. Whenever I look at [the Sanderson window], it makes me feel like a double gin and tonic.”

The cost of the documentary was covered in part by the sale of 300 smaller studio pieces by Goldmark Art Gallery, in Uppingham, Leicestershire. Interest in these editions was created in an unusual way: by inviting collectors to a lunch where Patrick Reyntiens, then 85 and still the consummate performer and teacher, worked live, painting small panels extempore, and generating a mounting interest in the gathered guests. The painted pieces were leaded by John Reyntiens and sold in two editions, one of 200 pieces in 2010 and one of 100 pieces in 2011.

A friend of 70 years’ standing was delighted that Reyntiens would sometimes telephone 'to speak to you without introducing himself, but carry you along in the conversation that was going through his head at the time'

During Anne’s final illness, Reyntiens filled a set of notebooks with ink and wash drawings of phenomenal range and energy—landscapes, cityscapes, concert and party scenes. In 2010, in his 85th year, he recalled having a dream when he was 75 in which “my guardian angel came to me and said ‘You’ll live till you’re 96’. And I said ‘Oh how wonderful’ and he said ‘You’ll have to work for it’. So there we are, I’m still working.” He died seven weeks short of his 96th birthday.

A friend of 70 years’ standing was delighted that Reyntiens would sometimes telephone “to speak to you without introducing himself, but carry you along in the conversation that was going through his head at the time”. The fluent Reyntiens river of thought, just like the rivers of light that flowed through his stained glass, ran to the end. His final piece, completed in 2018, when he was 92, was for a panel, A Good Night’s Sleep.

Patrick Reyntiens's final commission, A Good Night's Sleep, panel, 2018 Courtesy of Reyntiens Trust

Nicholas Patrick Reyntiens; born London 11 December 1925; Head of fine art, Central School of Art and Design, London 1976-86; OBE 1976; married 1953 Anne Bruce (died 2006; two sons, two daughters); died 25 October 2021.