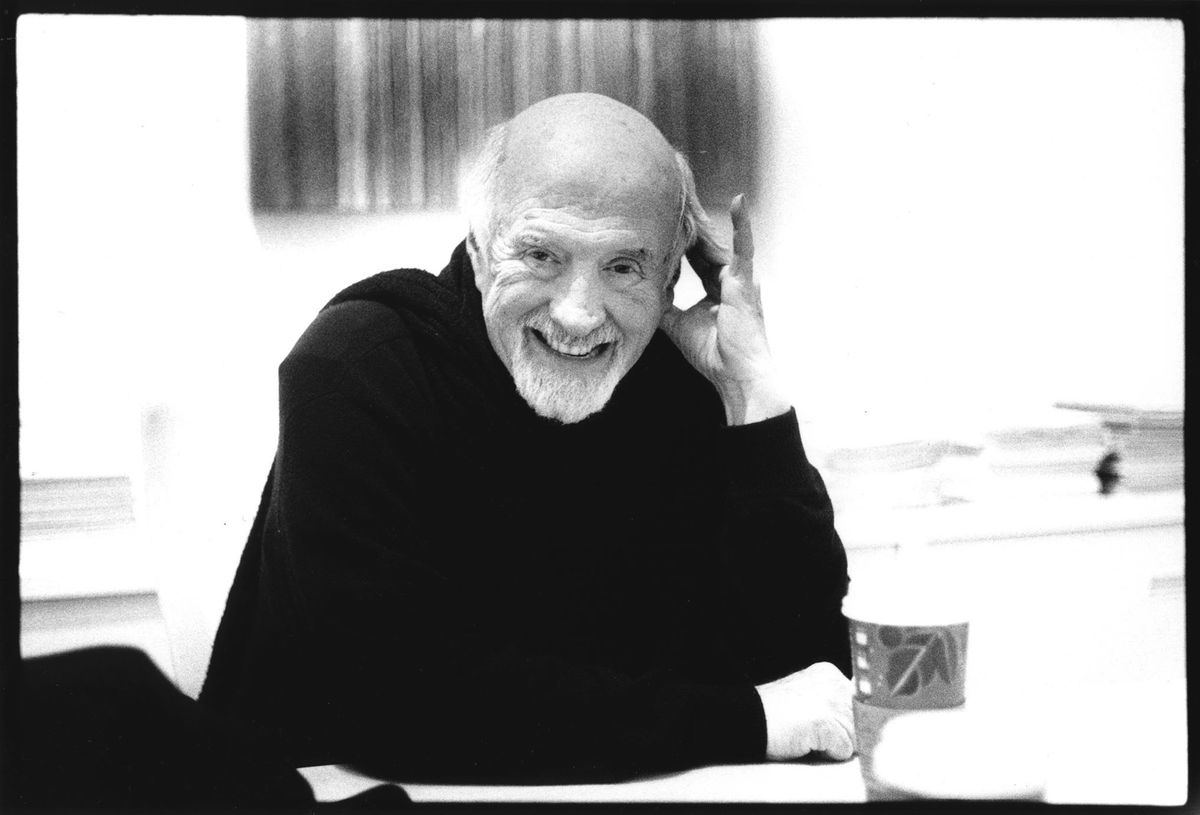

Dave Hickey, the totemic cultural critic whose quick-witted work both democratised and bisected the art world, has died at 82. Hickey died in his home in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The cause of death was heart disease.

Armed with humour, a deep intellect and an alchemical ability to mix high and low, Hickey was unafraid of integrating talk of sports and food into his discussion of fine art, concocting a sort of intentional bathos that was all his own. He saw art not as a highbrow disruption of our lives but as an everyday occurrence, a view that gave shape to prophetic assertions such as “the title of artist has to be earned” and “all we do by ignoring the live effects of art is suppress the fact that these experiences, in one way or another, inform our every waking hour”.

Hickey was born in 1938 in Fort Worth, Texas. His father was a jazz musician and a car salesman, and his mother was a painter and a businesswoman; neither of them found great commercial success from their artistic pursuits in their lifetimes. As a child, Hickey travelled the country with his father, who was often on the road looking for work. When Hickey was only 11, his father died by suicide. After a period of time living with his grandparents, Hickey enrolled in Texas Christian University, graduating in 1961, then earning his MA from the University of Texas in 1963.

In 1967, he moved to Austin to pursue a PhD in linguistics, at which point he opened the short-lived but influential gallery A Clean, Well Lighted Place, which was named for the Ernest Hemingway story. The gallery shuttered shortly after Hickey dropped out of the PhD program and moved to New York City in 1971 to take a job as executive editor of Art in America. In New York, Hickey quickly became a major figure in cultural criticism, one who prided himself on creating work that possessed a trait not often seen in the art world: accessibility.

“Most writing about art these days is so bad that my secular readership has disappeared,” he lamented in a 2014 interview with the New York Observer. “Nobody but professionals and grad students even look at it. So no more emails from civilians, no more notes from John Updike or Steve Martin, no more crazy hipsters from Berkeley knocking on my door.”

In New York, he began writing for just about every major outlet there was at the time, including Artforum, Harper’s, Interview, the New York Times, Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair and the Village Voice.

“His essay made paintings that I loved intelligible in plainspoken, even obvious ways that the critical baggage of High Art pretensions had hitherto obscured,” writes Christopher Knight, the Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic who was a friend of Hickey’s, in an elegiac piece for the Los Angeles Times. “But it was the music in his writing that kept me going. Hickey, a brilliant and cantankerous wit, wrote for the ear. His work needed reading, not scanning, and rewarded effort with pleasure.”

In 1993, Hickey published The Invisible Dragon: Four Essays on Beauty and in 1997 he published Air Guitar: Essays on Art and Democracy, with the University of Chicago Press and Art Issues Press, respectively. The books—particularly Air Guitar, which Knight calls “easily the most widely read book of art criticism to appear in our time”—melded criticism with Hickey’s memoiristic tendencies. Incorporating talk of basketball, Liberace and Hank Williams alongside art writing of the highest caliber, these books are often regarded as seminal, albeit bifurcating, works of the genre.

Throughout the 1990s, Hickey continued to write but spent a growing share of his time teaching. First at the University of Nevada in Las Vegas, where he taught for 20 years, and then at the University of New Mexico in Santa Fe, with stints at Harvard, Yale and the Otis College of Art and Design dotted throughout.

While he often shunned the art world, his belief in art propelled him forward towards further books and accolades. In 1994, he received the College Art Association’s Frank Jewett Mather Award for art criticism, in 2001 he was a MacArthur “genius” grant recipient (though, living in Vegas at the time, he “proceeded to deposit most of the half-million-dollar prize into video poker machines”, per Knight) and in 20016 he was awarded a Peabody.

“That’s why I became a cultural journalist. I wanted to write, but I wanted to have adventures—I wanted to sit on the beach with Keith Richards and some dude playing the trombone,” Hickey told novelist Sheila Heti in a 2007 interview with The Baffler. “I wanted to be where it was, and I sacrificed a great deal of literary value for that, but I had a hell of a lot of fun. Back in the 1970s and ’60s, if you could do this, to length and on time—and not many people could, nor can they now—then you could go anywhere you wanted to, and look at whatever you wanted to. But it makes me happy that I set out to make a living out of the writing life and I have done it. Not a great life, of course, or a famous one, but a really cool one. The culture afforded me that, and I am sad that that life is disappearing.”