The NFT collection Art Wars has prompted the wrath of major artists after it sold tokens linked to their physical works of art for “millions”, allegedly without their permission or knowledge.

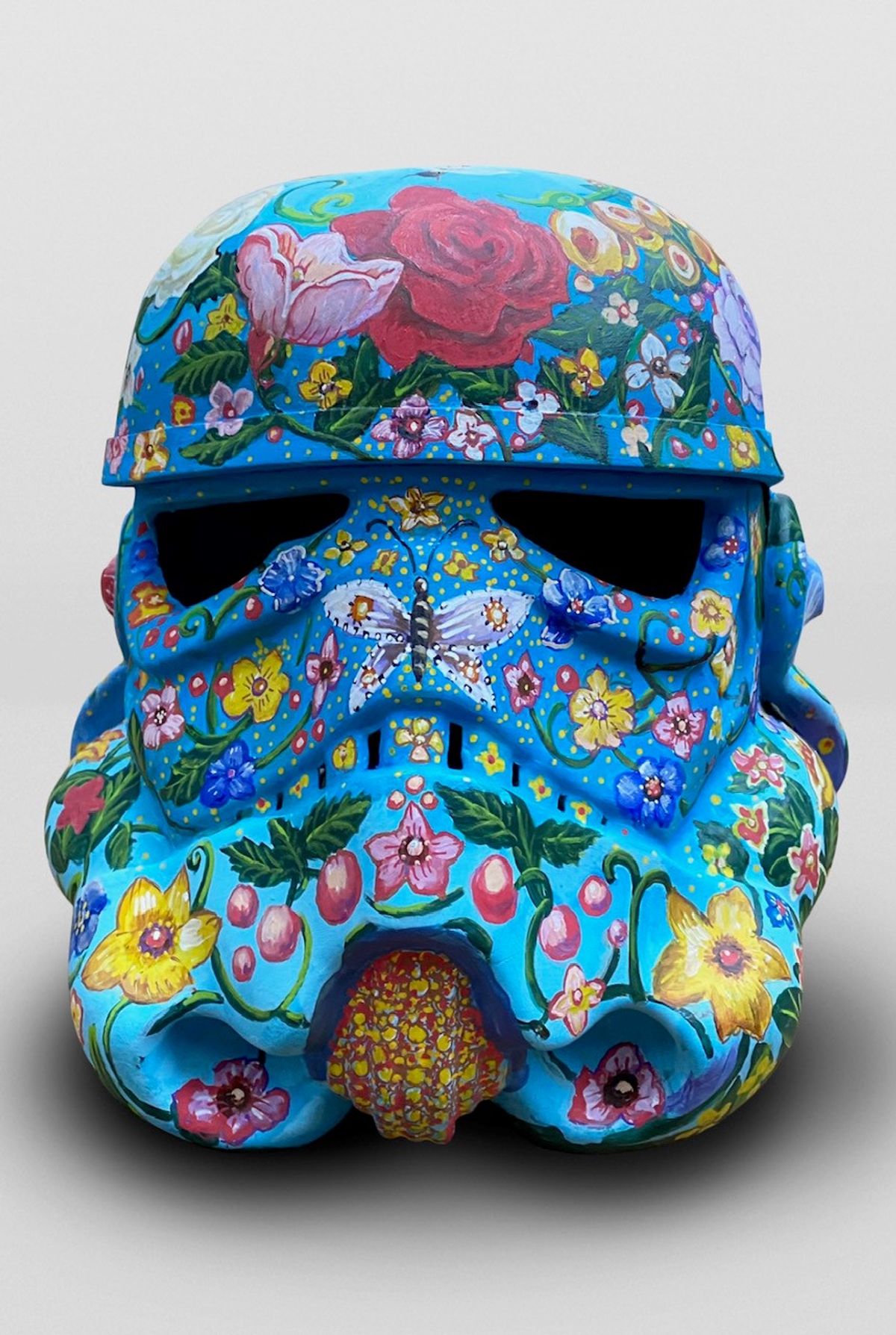

The online project was launched earlier this year by the London-based artist and curator Ben Moore, in conjunction with the US developers DeFi Network and photographer Bran Symondson. The NFTs are based on the curator’s previous project which saw major artists (including Anish Kapoor, Jake & Dinos Chapman, David Bailey and Damien Hirst) designing physical Stormtrooper helmets, a number of which were displayed at Saatchi Gallery in 2013. The project has had various incarnations between 2007 and this year.

In the digital version of the project, 1,138 NFTs were created, around 100 of which were linked to photographs of these earlier physical works. They have resulted in 1.6ETH of transactions (around £5m at time of writing) since the project’s launch earlier this month.

While Damien Hirst’s team were quick to request the relevant work’s removal prior to sale, most artists only became aware of the Art Wars project after the launch. At least three more works have now being taken down by Opensea (the NFT platform on which the project is hosted) until the dispute is resolved.

Jon Sharples, an art and intellectual property lawyer with Canvas Art Law who is representing a number of the artists in the case, argues that Moore did not own the original works of art, nor have the licence to create NFTs or other derivatives from them. Aside from a newsletter notifying artists of the project, it is also argued that no attempt was made to seek permission.

Chemical X’s Stormtrooper helmet Star Tripper (2017), an NFT of which was offered by Art Wars

Courtesy of Chemical X

“In time it may well be that ‘Web 3.0’ [third-generation, decentralised internet] causes a shift in our collective sense of what uses of others’ IP is fair, and how we value and identify original work, but in the short term it doesn’t work to say that NFTs represent some sort of grey area in which the existing rules don’t apply,” Sharples says. “This is the first episode involving a number of high-profile artists from the contemporary art world having their work attached to NFTs without their permission.”

In response, Ben Moore tells The Art Newspaper that Art Wars “has always been a charitable endeavour” since its launch in 2013, with proceeds going to the Missing People charity. He says: “We regret that some of the artists were taken by surprise, and have since expressed a preference not to be included—of course we've respected those wishes. We really value the relationship we've built with them over that time. We're still very excited about the NFT project as it has successfully raised £30,000 for the charity.” Moore adds that Art Wars plans to release further NFTs and all artists that remain involved will “receive royalties in the usual way”.

Providing a historic precedent to the matter is an intellectual property battle over the original stormtrooper helmets. In a 2011 UK case, Lucas Film Limited unsuccessfully challenged the costume model maker, Andrew Ainsworth, over design of the helmets, which Lucas Film claimed were “art or sculpture” under copyright law.

It is also not the first case to raise challenges of the translation of intellectual property law to new ways of trading online. In April, the sale of a Basquiat NFT, Free Comb with a Pagoda, was withdrawn when the artist’s estate made it clear that the owner did not possess the copyright and IP rights being offered for sale with the work.

“It’s really important to take action, the NFT space is a bit like the Wild West and in some ways that makes it fun,” says the London-based artist, Unskilled Worker, who was made aware of her work being used in the Art Wars NFT collection via Twitter. “However, if exploiting artist’s IP goes unchallenged, this behaviour will ruin and corrupt what is a truly exciting space for artists and collectors alike”.

Aretha Campbell, an artists’ manager at Bridgeman Images, which represents the artists Antony Micallef and Miranda Donovan in this emerging dispute,says: “Whilst we totally appreciate there is a rush to profit, it is better to wait for the right partner that fits with the artist’s brand and ensure any legal uncertainties have been addressed from the start.”

Sharples says the artists he represents are now “working out and coordinating their next steps for seeking full legal redress.”