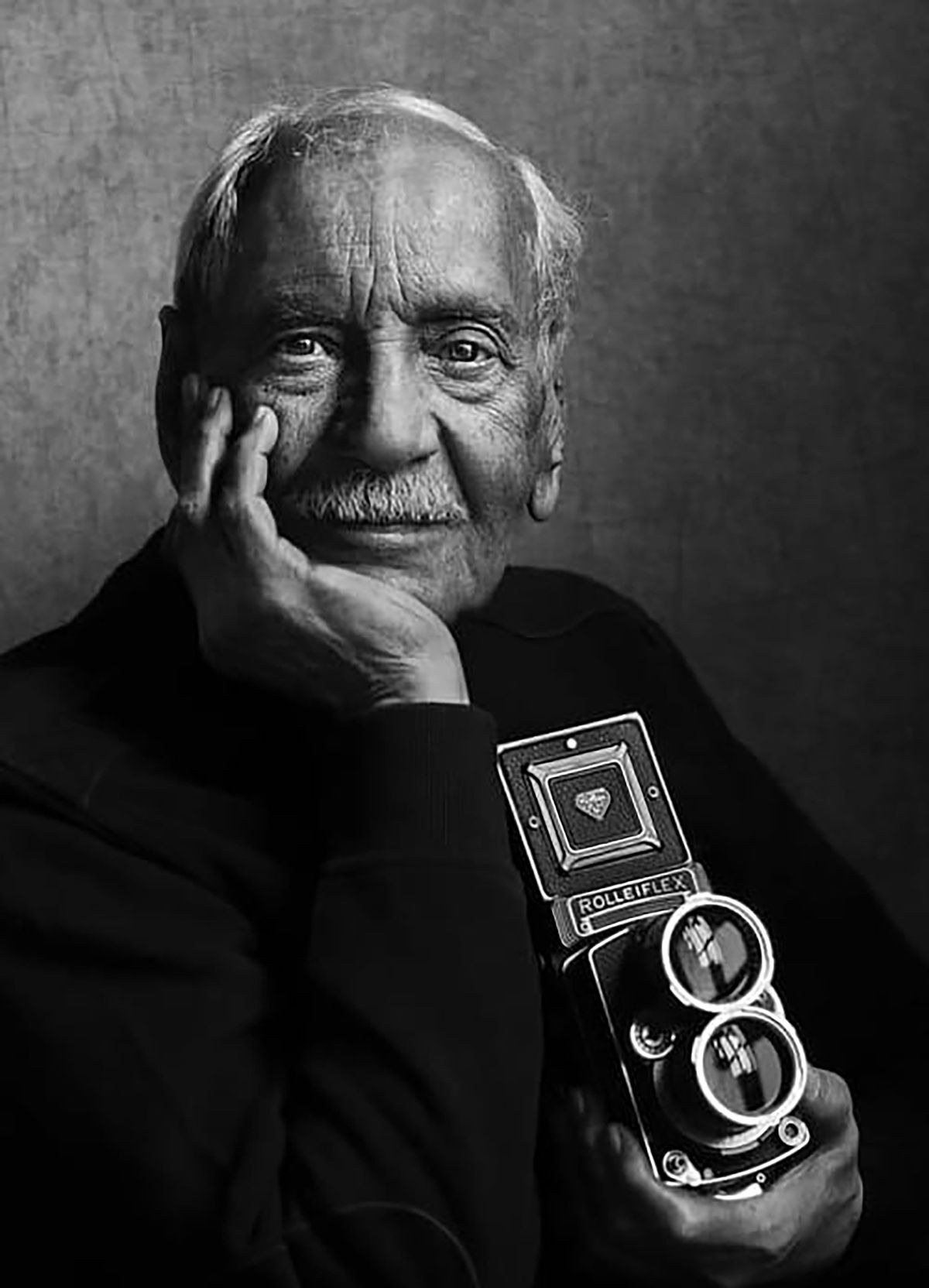

Latif Al Ani, the beloved “father of Iraqi photography”, died in Baghdad on 18 November aged 89, four months after being diagnosed with bone marrow cancer. Born in Karbala in 1932, he first took up photography in 1947, aged 15. He became known for chronicling how the fast-modernising nation came to see itself in the 1950s, 60s and 70s: cosmopolitan, civilised and above all modern, while still honouring its Sumerian and Mesomopotamian origins.

“With Iraq as his primary material, Latif had the fortune to document (in retrospect) through photography, Iraq’s golden age, but also to create images with the Modernist sensibility of the time, similar to what artists such as Jawad Salim were doing in painting,” says Tamara Chalabi, the chair and cofounder of the Ruya Foundation, which organised an exhibition of his work in London in 2017.

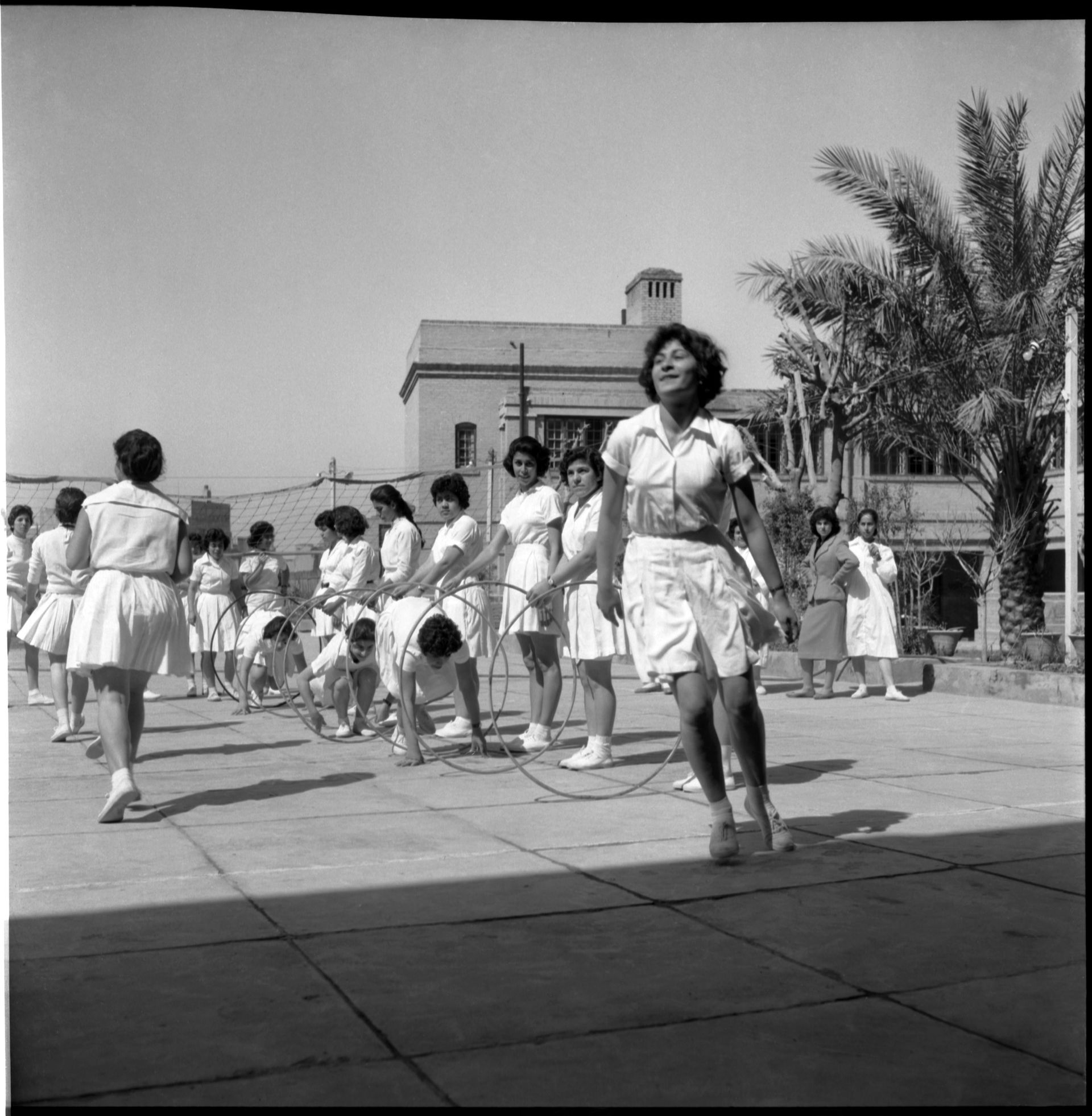

The glamour many of his images depict tends to be received with a nostalgic, elegiac air today, but Al Ani also emphasised the ancient and the archaeological. His photographs are characterised by a chiaroscuro effect that has a temporal dimension, contrasting history and the present. “His lens captured a moment in the history of Iraq that I always hear about but never could have imagined,” says writer Mariam al-Dabbagh. “To see photos of the Baghdad that my parents once loved and lived in was only possible through Latif.”

Latif Al Ani, Sports in School, Baghdad (1960) Latif Al Ani collection, courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation, Beirut

Al Ani began his career in 1954 at the Iraqi Petroleum Company’s in-house publication Ahl al-Naft, or People of Oil. Mentored by photography director Jack Percival, he experimented with aerial photography to capture the infrastructures of industry: oil rigs, pipelines and so on.

“Notwithstanding the colonial overtone, it was a fruitful collaboration and reflected an aspect of the Middle East that was more fluid in its exchange with the West, not unlike the Iraqi artists who were sent on scholarships to the Slade School and Beaux Arts in 1930s and 1940s,” Chalabi says. “Latif had a large canvas to work with—Iraq. Yet he was not only a documentary photographer because he was always interested in depicting beauty in every shot.” She adds his archive also includes lesser-known still lifes and abstract works.

In 1960, Al Ani moved to what became the Ministry of Culture and set up its photography department. In keeping with the socialist currents of the time, Al Ani’s subjects were quotidian and humble farmers, factory workers, and other ordinary people, as well as machinery, military parades and rallies, and other facets of public life. The department’s magazine bore a title that could well apply to his entire oeuvre: New Iraq. In the increasingly authoritarian 1970s, Al Ani headed up the photography division at the Iraqi News Agency. When Saddam Hussain came to power and banned public photography in 1979, he put his camera down forever.

Latif Al Ani, Mandean family, Baghdad (1961) Latif Al Ani collection, courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation, Beirut

The photographer remained in Baghdad through the ensuing conflicts, including the Iran-Iraq war and the Islamic State. Dabbagh relates an anecdote Al Ani told her in 2018, about a European artist who asked him why he did not leave. “Latif was baffled by this question, first at the audacity of questioning the reasoning behind staying put, but also, to quote his words, ‘Baghdad mako mithilha.’ Baghdad is a city like no other.”

Over the decades, Al Ani’s work was all but forgotten. Artist Yto Barrada met him on a 2000 research trip, and arranged for a large selection of his negatives to be acquired by the Arab Image Foundation (AIF) in Beirut. “Like his Arabic name indicates, Latif was a gentle and kind soul. He remained in contact with us until a few days before he passed away,” says Heba Hage-Felder, AIF’s director. “His trust in the foundation’s team to care for and disseminate his works was unrelenting.”

It was not until the 2015 Venice Biennale, at the Iraqi pavilion commissioned by the Ruya Foundation and curated by SMAK director Philippe Van Cauteren, that the world at large was introduced to Al Ani. A monograph and a number of international exhibitions followed, including a major retrospective at the Sharjah Art Foundation curated by Hoor al-Qasimi in 2018.

Latif Al Ani, Music lesson, School of Music, Baghdad (1960) Latif Al Ani collection, courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation, Beirut

Chalabi explains that the Iraqi art scene today is fragile, dominated by the state and somewhat dysfunctional, with photography and film not even recognised as art forms by the official art association. As such, when she and Van Cauteren visited the AIF archives in 2014, “it was very clear that he should be in the show. Not only because he was a photographer, but because of the richness of his material and also because he was forgotten. During his working years, Latif’s photography was viewed in the context of the institutions that employed him—it was part of a collective means of communication. Today his work stands a much greater chance of influencing photographers individually as he is no longer in the shadows.”

In 2019, Al Ani had his first solo exhibition with Dubai’s Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde. “Like his photos, which opened the world’s eyes to the richness of his country, the man himself was sensitive, generous, and compelling,” says Van Den Eynde.

Hage-Felder adds, “What he captured of Iraq and about Iraq will endure the test of time. Each image is a narrative and a hint of what we all carry with us when all else falls apart—a testimony, a memory and a story to tell.”