They call her the Stargazer for her delicate head looking skywards: this Anatolian marble statuette carved more than 5,000 years ago, which seems so modern in its abstract form, opens the displays of the new Al Thani galleries in Paris’s historic Hôtel de la Marine. A selection of 120 treasures from the collection of Sheikh Hamad bin Abdullah, a member of Qatar’s royal family, goes on show on 18 November in the monumental palace in Place de la Concorde, a “mini-Versailles” which opened in June after four years of restoration.

Designed by Ange-Jacques Gabriel, the architect of Louis XV, the Hôtel de la Marine was from 1774 to 1797 the Garde-Meuble of the Crown, the repository of royal furniture, works of art and jewels, which Louis XVI opened to the public as a museum. The first-floor wing that today hosts the Al Thani collection once housed the tapestries of the Crown. From June it has been possible to visit the other areas of the monument: the 19th-century reception rooms and the apartments of the Garde-Meuble intendents.

Hôtel de la Marine on the Place de la Concorde in Paris, where the Al Thani collection will be displayed for the next 20 years Photo: Jean-Pierre Delagarde/Centre des Monuments Nationaux

At a media presentation of the Al Thani galleries earlier this week, the collection’s chief curator, Amin Jaffer, described Sheikh Hamad as “a lover of French culture” who “has been collecting 17th and 18th-century furniture in the French taste since he was young”. In 2011, he “began to acquire museum-level art objects” but “initially he did not think of either exhibiting them or opening a museum”.

The shift, Jaffer said, came from a “decisive” meeting with the then director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Thomas Campbell, who “immediately understood that [the collection] deserved to be presented to the public”. In 2014, the New York museum organised the first exhibition of Mughal jewels in the collection, which later travelled to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (2015) and the Doge’s Palace in Venice (2017). In 2019, more than 300 of those Indian jewels were auctioned at Christie’s in New York for $109m in total.

The Stargazer idol, presented in the first Al Thani gallery ©The Al Thani Collection 2021. Photo: Marc Domage

If the works in the Al Thani collection are used to travelling to museums all over the world (some are currently on display at the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg until 15 January), this is the first time they have found a permanent home. In 2018, the Al Thani Collection Foundation signed an agreement with the Centre des Monuments Nationaux, the public body that manages nearly 100 monuments across France, that allows for 400 sq. m of exhibition space at the Hôtel de la Marine for the next 20 years, in exchange for a €1m rental fee every year. The foundation also contributed to the €132m restoration of the monument and the acquisition, for more than €1m, of an 18th-century commode by Jean-Henri Riesener, Marie Antoinette’s favourite cabinetmaker.

The Qatari prince—who is also the owner of the Hôtel Lambert in Paris, a historic residence on the Île Saint-Louis—could not have chosen a more prestigious showcase for his collection, which is rich in 6,000 works, spanning 5,000 years of history. The Hôtel de la Marine is full of history: it is where Marie Antoinette’s death warrant was signed in 1793 and where the wedding of Napoleon I and Marie-Louise took place in 1810. From the Revolution until 2015, it served as the headquarters of the French navy.

A Fang reliquary head from Gabon (1770-1850), featured in a gallery on the theme of the face through the ages Photo: Luana De Micco

The exhibition design of the four Al Thani galleries, whose historic interiors have not survived, was undertaken by the Paris-based Japanese architect Tsuyoshi Tane, who was recommended to Sheikh Hamad by Hiroshi Sugimoto. “Although attracted by the French 18th century, the sheikh wanted a state-of-the-art museum,” Jaffer explains. “He selected the works himself, those most important to him. So this is not a classic museum itinerary, since it is the result of personal choice. The entire collection reflects the taste of the sheikh, who acquires works according to their refinement, but also based on emotional affinity. It reflects the variety of his interests.”

A shower of gilded flowers, inspired by the rocaille motifs of the Hôtel’s historic apartments, greets visitors in an almost magical atmosphere. In the first room, seven emblematic objects from different eras are installed in individual display cases, each with its own story to tell, including an Egyptian pharaoh’s head in red jasper (1475-1292BC) and a rare Mayan mask pendant (AD200-600), in addition to the Stargazer idol.

The other rooms have an elegant and minimalist setting. The second, on the theme of the face through the ages, features a medieval chalcedony bust of the emperor Hadrian made in the court workshop of Frederick II of Swabia and a Fang reliquary head from Gabon (1770-1850).

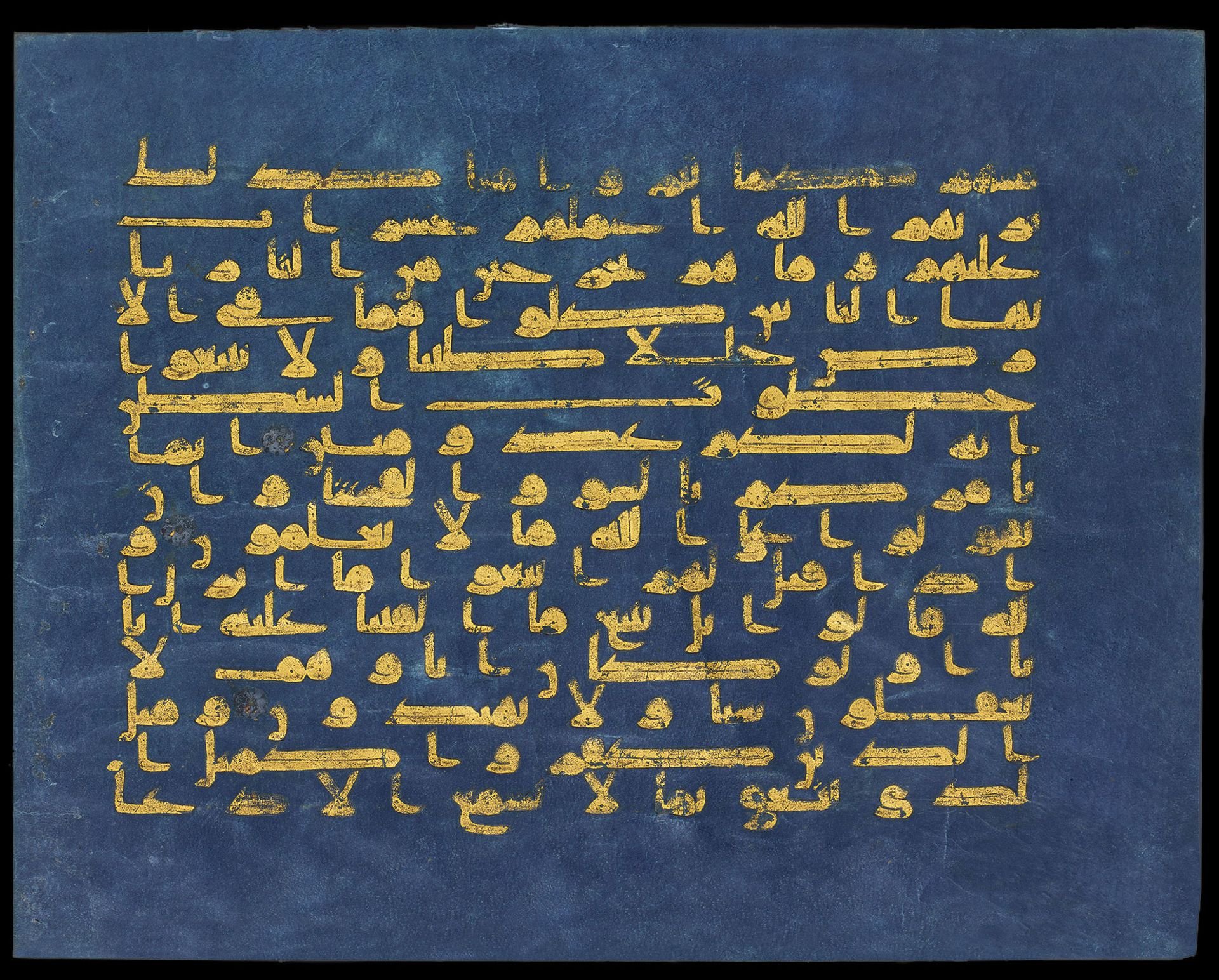

Folio from the Blue Quran (ninth-century) © The Al Thani Collection 2018. Photo: Matt Pia

A gold cup from Marlik, northwest Iran (1100-900BC) © The Al Thani Collection 2017. Photo: Prudence Cuming Ltd

The third room hosts temporary exhibitions, with two scheduled a year. The inaugural show, which draws on the Al Thani collection, is titled Masterpieces of the Arts of Islam, among them Ottoman sabers and a folio from the ancient Blue Quran. The next exhibition is being organised for March 2022 in collaboration with the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon.

The fourth and final room houses “ancient treasures”: precious objects in gold, silver, agate, or covered with lapis lazuli, from Egypt, Iran and Greece, including a Tibetan table service in gold and turquoise (Yarlung dynasty, AD600-800) and a gold cup from Marlik in Iran, hammered from a single gold sheet (1100-900BC). The displays close with a selection of Olmec objects, including a crouching dwarf statuette from 900-600BC.

Could a new museum for the Al Thani collection open in the future, perhaps in another art capital of the world? “For the moment we are concentrating on our project here at the Hôtel de la Marine,” Jaffer says. “The goal is to propose quality exhibitions and catalogues and develop a programme of conferences, debates, readings. There is no desire to build a galaxy of museums, as other collectors do, at least not for the next 20 years!”