I have mixed feelings whenever I hear that yet another Black artist has sold at auction in New York, London or Hong Kong for record setting figures. On one hand, I’m glad to see Black artists securing the bag and, in their lifetime, benefitting from the wealth generated by their work. If an auction price is high, subsequent works created by said artist can also be sold for high prices.

On the other hand, I’m concerned about the manner in which the works of these stratospheric Black artists are presented. Whenever a Black artist breaks through, their ‘newness’ is often highlighted. There’s an emphasis on ‘discovery’ and the ‘discoverer’ is often from outside the community of said Black artist. The discoverer has never seen anything like it and so therefore, nothing like this has ever been created before. Either this, or the discoverer can only view the piece through the lens of Western art history.

Some artists insist that the Black forerunners to their work be acknowledged. Kerry James Marshall, for example, often cites the importance of Charles White to the development of his practice. But it shouldn’t be the artist’s job to situate themselves in the relevant art history. That should be for curators, commentators, art historians and pesky writers like me, with a monthly column in The Art Newspaper.

So let’s take Amoako Boafo. Boafo is a Ghanaian artist whose portraits of Black subjects have caused a storm in the art world. He’s set auction records, collaborated with fashion houses and sent a triptych into space on Jeff Bezo’s rocket. His work is accessible and appealing. The subjects are often pictured wearing bright clothing or set against colourful backgrounds. Their gaze usually confronts the viewer. What particularly stands out is Boafo’s technique. He paints with his fingers and you can literally see the artist’s hand in his work, in every single stroke of paint. It gives the work motion. The subject is still but their skin is moving; their skin is alive.

If you’ve heard of Amoako Boafo, you should also have heard of the Ghanaian artist Ablade Glover. Born in 1934, Glover studied art education at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, is highly decorated in Ghana and is a Life Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts in London. Glover also eschews the use of a paint brush but he uses a palette knife not his fingers. The effect in his work is similar to the effect in Boafo’s work. You can see the artist’s hand, every single stroke of the palette knife on the canvas. There is motion in his paintings, especially in his series on market women.

Ablade Glover, Orange Profile I (2019) Courtesy of the Artist and October Gallery, London

Of course, the projects of Glover and Boako are different. Glover is interested in the beauty and motion of a crowd, while Boako focuses on the singularity of individuals. Glover’s people are part of a Ghanaian community. Boafo’s subjects stand out and stand alone, perhaps a comment on the individual way of life in the West. But there is enough similarity in the work for the names of the two artists to be paired.

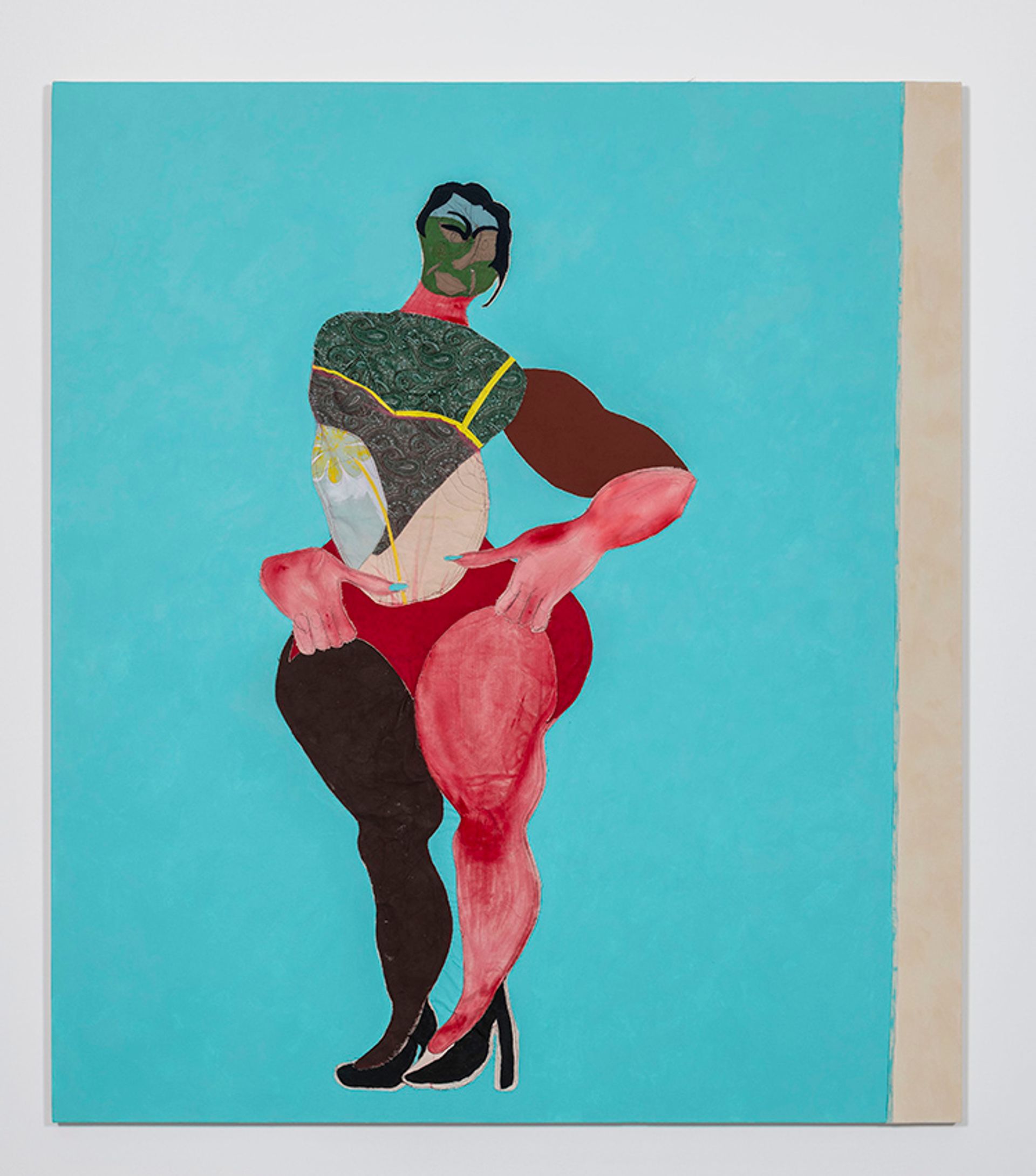

Let us now consider Tschabalala Self. Self depicts the female form using fabric, paint and discarded pieces of her old work. The pieces are bold and exciting. Her figures are large and confident, full bosomed and full bottomed, the body type of many Black women excluded from the pages of fashion magazines. The figures are both a celebration of the Black body and a critique of the obsession with and fetishisation of the Black female form.

Tschabalala Self, Leotard (2019) Courtesy of the artist, PIlar Corrias, London and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich / New York

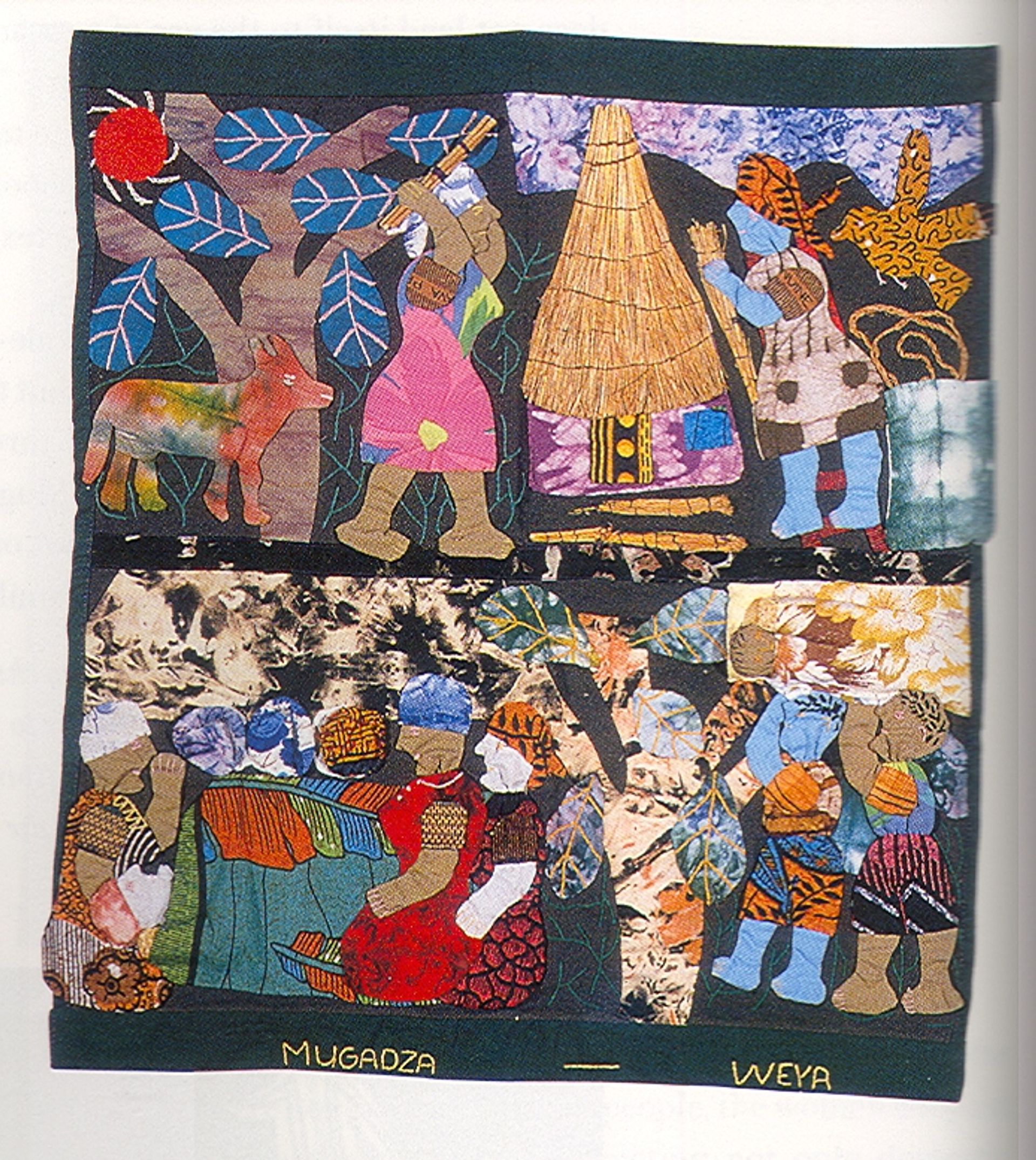

Self herself, has pointed to Romare Bearden and Faith Ringgold as influences. Some commentators see Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning and Thomas Hart Benton. To Ringgold and Bearden, I would like to add the Weya Women artists of Zimbabwe. Their art developed out of a community workshop designed to teach sewing skills. The pieces depict the lives of Zimbabwean women in fabric wall hangings. The female Zimbabwean experience is centred in these works. Appliqué cloth figures go about their business, farming, cooking and raising children. The titles of the work often highlight the themes depicted. For example, Nerissa Mugadza’s, Life of an Unmarried Woman Who Has no Child.

I would love to see Self’s work and the work of the Weya Women artists in the same exhibition. Both centre the Black female experience. Both focus on the female body. Both use fabric in interesting ways.

Nerissa Mugadza’s, Life of an Unmarried Woman Who Has no Child © Nerissa Mugadza

Why is it important to ensure that today’s generation of Black and African artists are neither solely viewed through the lens of Western art history nor presented as ‘new’? What does it mean when the work of a Black artist is positioned as a standalone that belongs to no recognisable tradition? What does it mean when the only route to gaining respect for an artist’s work is to compare them to figures in the Western art cannon? In such presentations, I see echoes of Georg Hegel’s big, fat, falsehood: ‘Africa has no history.’

Some people are already wondering if the art world’s focus on Black and African artists is a ‘fad.’ To them I would say, your engagement with the work might be faddish but the work itself is part of a long, viable art tradition that has inspired artists all over the world. Black art is not new. Educate yourself.

Read more from Chibundu's Slade to Zaria series here.