The Salvator Mundi, which sold for $450m at Christie’s as a fully authenticated Leonardo, has been downgraded by curators at the Prado. It was bought in November 2017 by the Saudi culture minister, Prince Badr bin Abdullah, apparently for the Louvre Abu Dhabi.

The downgrading comes in the catalogue of the Prado exhibition Leonardo and the copy of the Mona Lisa, which runs in Madrid until 23 January 2022. Although individual specialists have questioned the status of the Gulf Salvator Mundi, the Prado decision represents the most critical response from a leading museum since the Christie’s sale.

The Prado’s verdict is recorded in the exhibition catalogue’s index, which has one list of paintings “by Leonardo”, and another for “attributed works, workshop or authorised and supervised by Leonardo”. The Gulf painting is recorded in the second category, where it is referred to as the Cook version (it was bought in 1900 by London-based Francis Cook). Although the show focuses on the Prado’s copy of Mona Lisa, it also deals with versions of other Leonardo compositions.

The Prado curator Ana Gonzáles Mozo comments in her catalogue essay that “some specialists consider that there was a now lost prototype [of Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi] while others think that the much debated Cook version is the original”. However, she suggests “there is no painted prototype” by Leonardo.

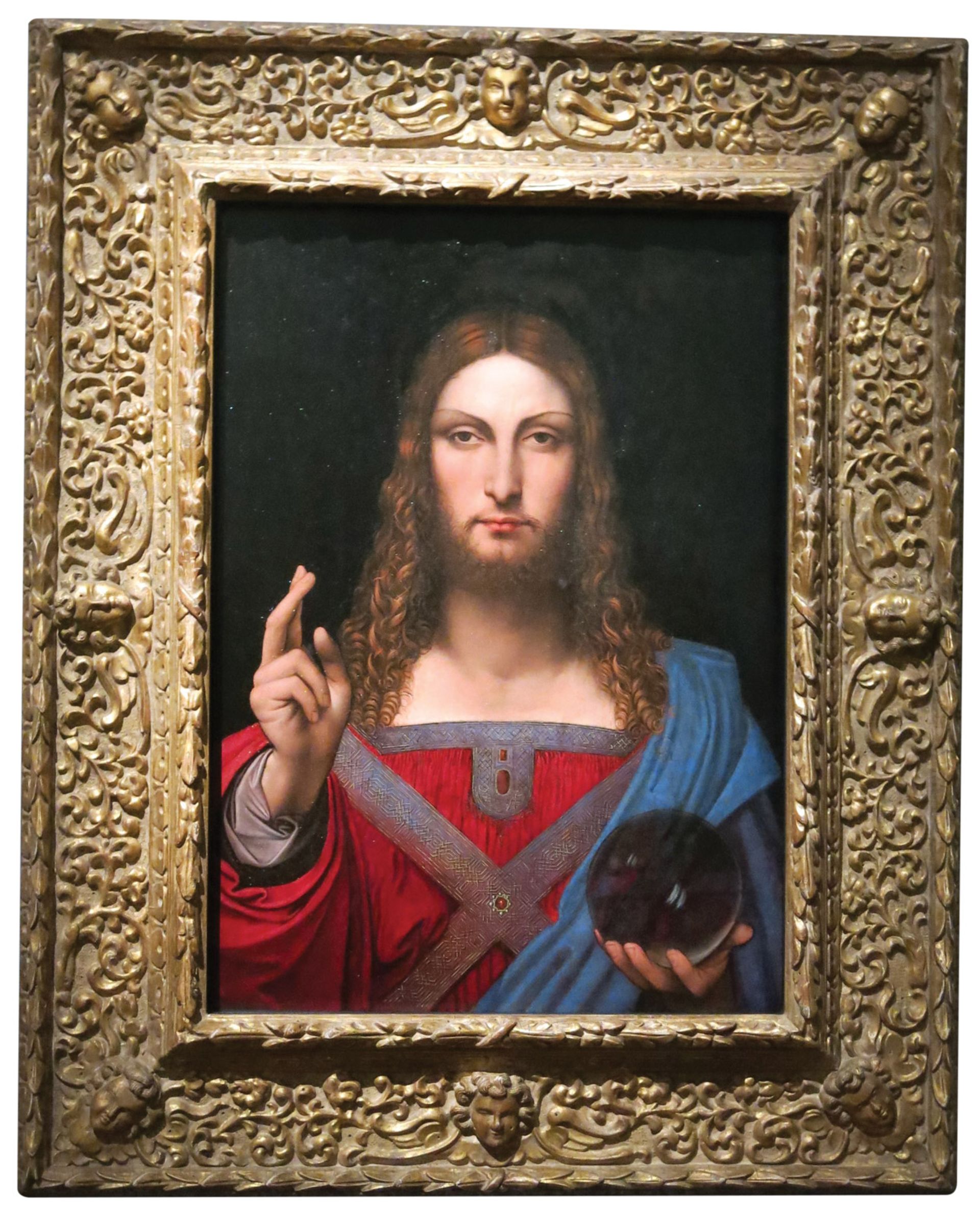

Mozo proposes that another copy of Salvator Mundi, the so-called Ganay version (1505-15), is the closest to Leonardo’s lost original. Acquired by the marquis de Ganay in 1939, it was sold at Sotheby’s in 1999 and is now in an anonymous private collection. Mozo argues that the skilled workshop artist who painted the Ganay Salvator Mundi was also responsible for the Prado’s early copy of the Mona Lisa (1507-16). Although the catalogue includes a full-page image of the Ganay Salvator Mundi, the Cook version is not even illustrated.

A Prado specialist suggests that the Ganay version (above) of Salvator Mundi is the closest to Leonardo’s lost original and was painted by the same artist as the early copy of Mona Lisa at the Prado collection © Tangopaso

The opening essay of the Prado catalogue is by Vincent Delieuvin, curator of the Musée du Louvre’s important 2019 Leonardo retrospective. He discusses the various views on the Gulf Salvator Mundi without giving much of his own opinion, although he does refer to “details of surprisingly poor quality”. Mozo would presumably have consulted closely with Delieuvin, who is a key collaborator on the current Prado exhibition.

Last month Delieuvin gave an online seminar for London’s Courtauld Institute on the challenges of organising the 2019 retrospective. He was asked why the Gulf version of the Salvator Mundi had not been included along with the Ganay picture, which was hung in the Louvre show. Delieuvin said the Gulf version had been requested but after “a long discussion” was not offered.

Delieuvin spoke unenthusiastically about the Gulf Salvator Mundi, saying that although “an interesting painting, it is not the most personal composition of Leonardo”. The Louvre curator told the Courtauld seminar that it “would have been good to have had it [the Gulf painting] near the nice Ganay version, which is a high-level workshop version”. The Ganay picture is also included in the Prado’s current show.

In the Prado catalogue, Delieuvin concludes of the Gulf Salvator Mundi: “It is to be hoped that a future permanent display of the work will allow it to be reanalysed with greater objectivity.”