If the goal of art is to transport the viewer, many exhibitions at museums (and galleries for that matter) take too sterile an approach. Work is presented on clinical white walls, as if they were being studied through a microscope in a classroom instead of warmly inviting appreciation. The recently opened Man Ray exhibition at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) focuses on the photographer’s fruitful years in Paris, from 1921 to 1940, and makes sure the City of Lights’ glowing milieu spills on to every corner of the expansive show.

Instead of the institutional white walls that surround most exhibitions, visitors walk through luxurious red curtains into a slightly dim, richly blue room, surrounded by portraits, each lit with a gentle spotlight as if it were on a stage, telling its story, through Man Ray’s camera, directly to you. A front row seat to an intimate show for one.

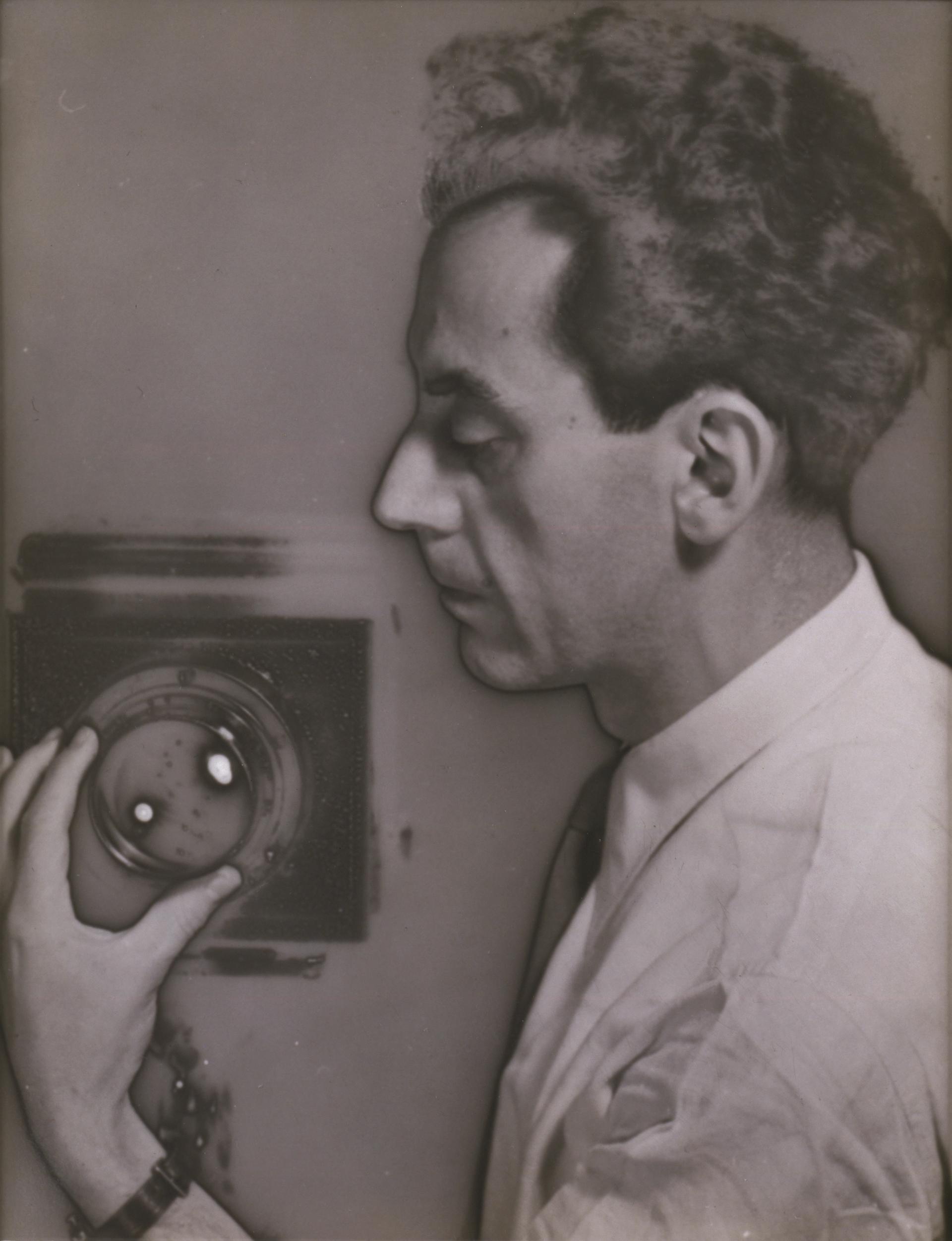

Man Ray Courtesy the Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society, NY/ADAGP, Paris 2021

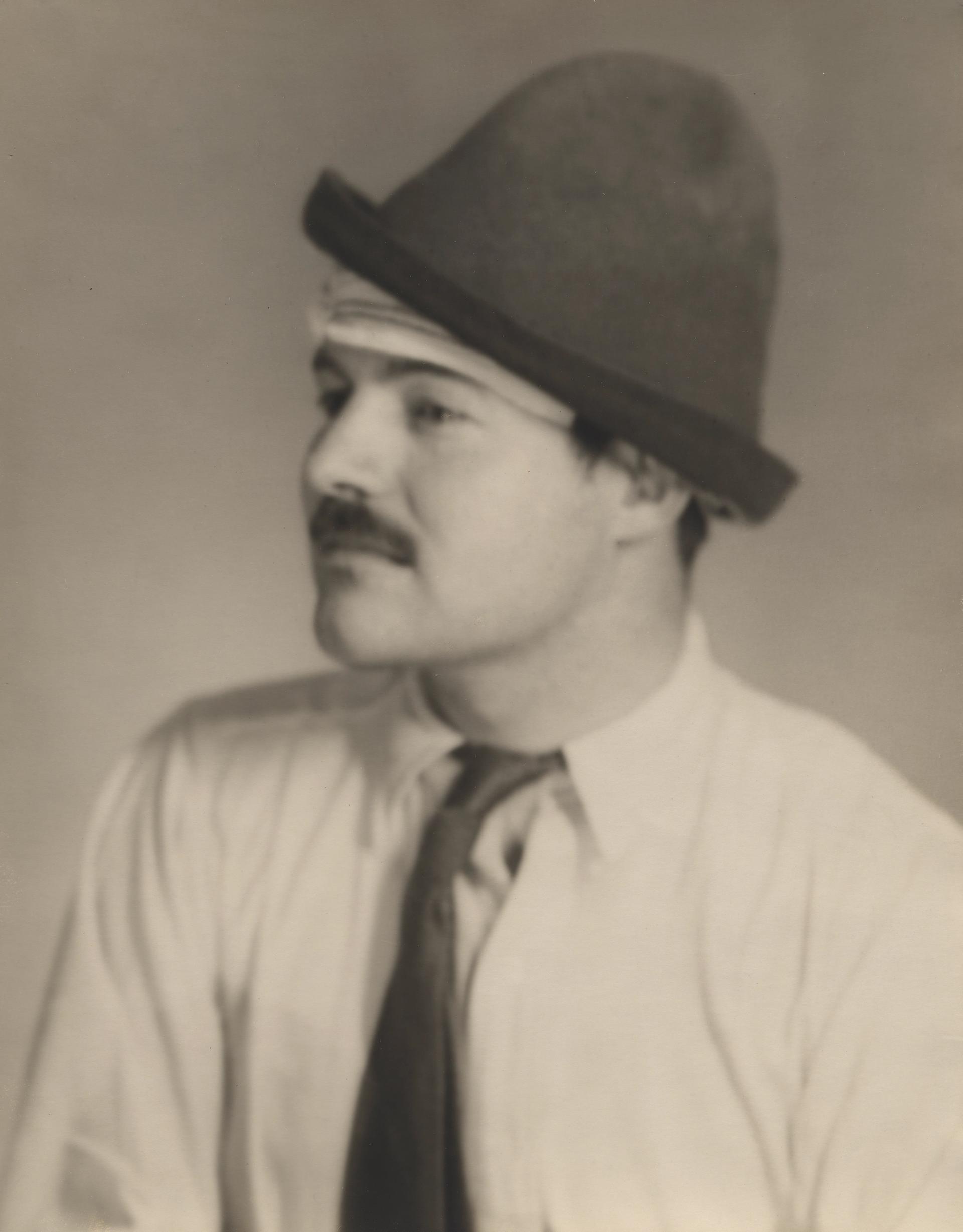

Given the time and place, there is no surprise that most of the performers are well known and held in high esteem. It is what the images are telling you that is surprising. Case in point, in the first room is a portrait of Ernest Hemingway. As famous for his sparse, hardboiled prose as he was for his alcohol tolerance and lust for adventure, young Papa looks dashing with a tightly bandaged forehead, no sign of discomfort on his face at all. One would never think the first aid stemmed from a bathroom incident during a get together at Man Ray’s. Hemingway, after a bathroom break, yanked on what he thought was the toilet chain but what was actually the cord to the casement window. Shards of glass fell from the sky like beaded necklaces on Mardi Gras. It was 1928. According to Man Ray: “There have been other pictures of him wounded, before and after this one, but none which gave him the same look of amusement and indifference to the ups and downs of his career.”

Ernest Hemingway (1928) Man Ray Courtesy the Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society, NY/ADAGP, Paris 2021

All the men of the age are there: Igor Stravinsky, James Joyce, Andre Breton, Picasso and Braque. Equally present are the era’s modern women, including Bernice Abbott, the rarely-as-well-photographed Gertrude Stein, Lee Miller and Virginia Woolf. The real stars, however, are the unknowns. Or rather, those unknown-to-us. “Man Ray used photography to challenge the artistic traditions and break boundaries, including fixed gender roles and racial barriers,” says Michael Taylor, the museum’s chief curator, who conceived the exhibition.

A couple look at a portrait of Lee Miller Photo by Daniel Cassady

There’s Kiki de Montparnasse, queen of the smokey eye, a cabaret performer known for sexually explicit songs at the Jockey nightclub, who sat for a cadre of the well-known avant-garde: Calder, Modigliani and Kertész. There are portraits of the elegant Barbette, a high-wire performer and trapeze artist who was born Vander Clyde Broadway. Insisting on the pronouns she and her while impersonating a woman for his act, Taylor says Barbette “captivated international audiences in the 1920s and 1930s with her gender fluidity and skills in aerial ballet…she performed her whole act in drag with the audience completely unaware they were watching a man until she took off her wig at the end of the performance”.

Barbette (1926), Man Ray, Courtesy the Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society, NY/ADAGP, Paris 2021

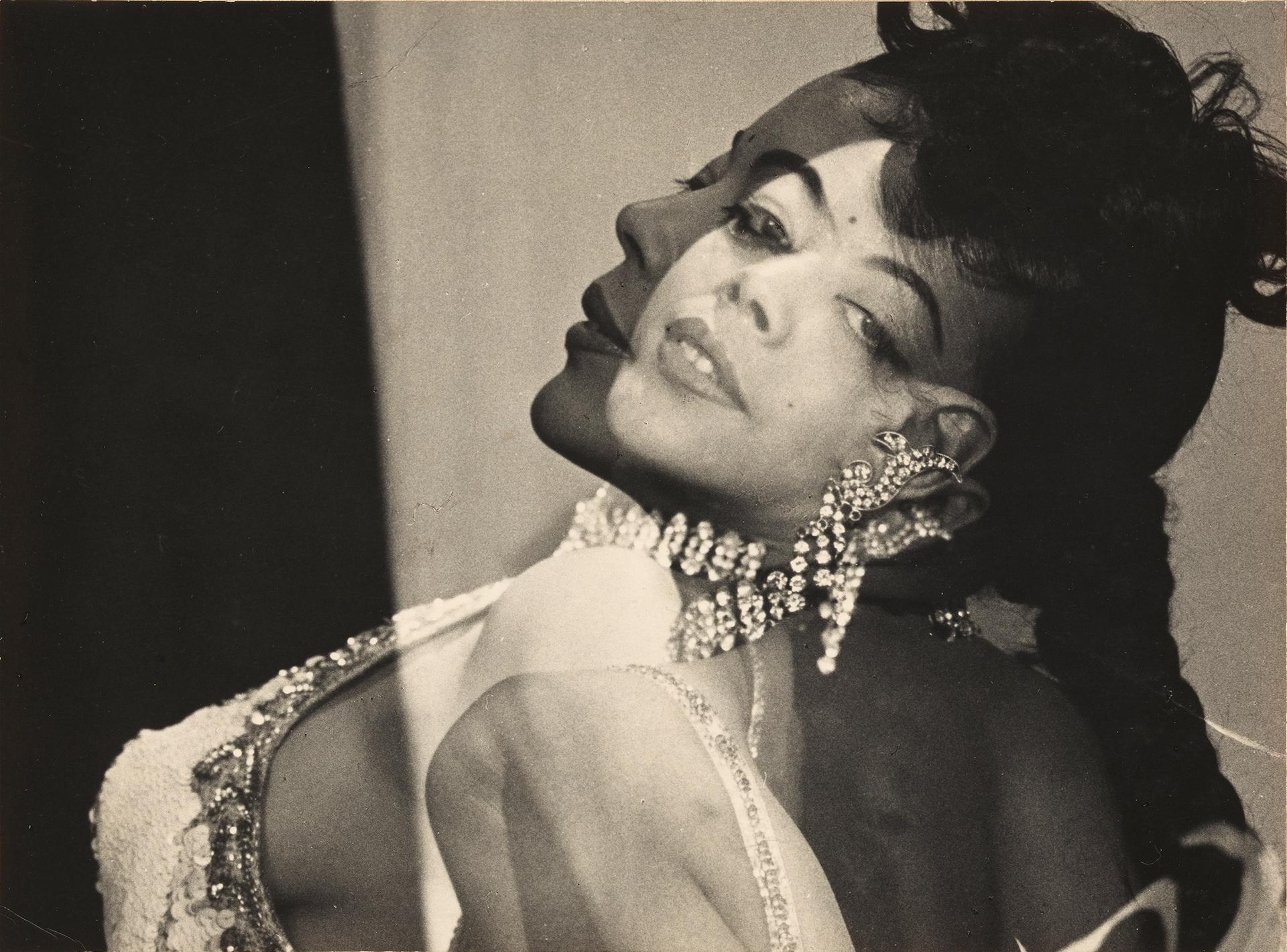

A special section of the exhibition is given to Ruby Richards, and rightly so. Born in St. Kitts, she was fresh from New York’s illustrious Cotton Club when she was chosen to replace the inimitable Josephine Baker in Paris’s Folies Bergére. Ruby is all but unknown today, but the exhibition gives her a full room, complete with Man Ray’s innovative double exposure portraits, a wall of ephemera including family pictures from her childhood in Harlem, New York, and her record, Zizi de Paris, sensuously playing through the speakers. An exhibition research assistant, Madeline Dugan, dug so deep into Richards’s past that she connected with living relatives, who had never met Ruby but knew of her, who were invited to the exhibition’s VIP preview. According to Taylor, Dugan also played a large role in educating the curatorial team in the correct use of gender pronouns and the intricacies of cultural appropriation.

Ruby Richards with Diamonds (ca. 1938), Man Ray Courtesy the Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society, NY/ADAGP, Paris 2021

Man Ray’s innovations are not excluded. A whole section of the exhibition is devoted to his light-bending portfolio Électricité (1931), a commercial project commissioned by the Paris Electric Company to promote the use of electrically powered household appliances. Comprised of ten “Rayographs” (another name for photograms), the portfolio pulses with kinetic energy. Fans spin with an otherworldly force, a fowl is perfectly cooked as by magic rays, and the Eiffel Tower swims in hi-wattage advertisements.

Images from Man Ray's portfolio Électricité (1931) Photo by Daniel Cassady

At the end of the exhibition there’s a table, on which sits a chess board Man Ray designed. What better way to end an exhibition that puts people first, both those being admired and those admiring, then to put visitors face to face. But fair warning: in case you thought no one was watching, a massively enlarged portrait of Man Ray’s closest friend, the chess master and artist Marcel Duchamp, and one of his most well-known opponents, Vitaly Halberstadt, hangs behind the board, urging you to think about how lucky you are to be among so much wonder.

• Man Ray: the Paris Years, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA, until 21 February 2022