You might have seen the adverts on your Facebook feed: an eye-catching sculpture made by an independent artist, offered in a run of repetitive sponsored ads, for a cut-rate price. But if you actually clicked on the link and bought the piece, you would likely either receive nothing or a cheap knockoff with only a passing resemblance to the work pictured in the post.

That is because it was just one of thousands of fake ads proliferating on the social media platform in recent months, likely posted by criminal organisations in China, Vietnam, Russia and other countries, according to groups who track such scams, using images of actual works stolen from artists’ websites or media coverage.

And the artists say Facebook is not doing enough to stop the scammers.

“Facebook needs to be held accountable,” says JL Cook, an artist based in Florida, whose meticulously lifelike bronze sculptures of rattlesnakes—originally commissioned by the Chiricahua Desert Museum in Rodeo, New Mexico to serve as doorhandles for its main entrance—have been copied and offered for sale on the social media platform for a fraction of what the works are worth.

The scam ads started popping up on Facebook less than 24 hours after she had created her own e-commerce website in June to sell works directly to collectors. “The listings were from these fraudulent stores that had stolen my images and stolen my descriptions and were claiming to sell the pieces,” Cook says.

“I thought it was just a one-off, and then dozens of these ads pop up from dozens of stores—and then hundreds of these ads pop up. I have reported over 900 ads on my rattlesnakes alone to Facebook. There are over 93 different URLs that are fake web companies that have my work on them.”

While Cook’s editioned sculptures normally sell for thousands of dollars, the ads on Facebook offered them for just $29.95—“and you get 50% off if you get three pairs,” she says.

Cook has reported the fake ads to Facebook, but the company has been slow to respond. Meanwhile, identical ads of her work have began to sprung up from other bogus sellers. The artist estimates she spends 3-4 hours each day dealing with the fake ads, or dealing with angry buyers who thought they had ordered her genuine bronze works only to receive poorly made plastic replicas or nothing at all.

The artists André Masters & CJ Munn stand with their work Icarus had a Sister. Courtesy of Masters & Munn.

The London-based artists André Masters & CJ Munn had a similar experience, seeing their limited-edition sculpture Icarus had a Sister appear in ads on Facebook earlier this year, with images taken from their website. “They've even stolen videos of us standing next to the work in the Business Design Center in London, where the work had been exhibited," Munn says.

The cast quartz sculpture depicts a winged figure emerging partially from the wall, her back to the viewer, and has more than 200, 3D-printed feathers that are individually finished and attached to the wings. They normally sell for £50,000, but the fake shops are offering it for $23.

Unsuspecting buyers who clicked on the fake Facebook ads received fraudulent, miniature copies of Masters & Munn's work Icarus had a Sister. Courtesy of Masters & Munn.

“Initially it was quite insulting that so many people thought they could buy it,” Munn says. “People thought, for their $20, they were going to get a life-size, beautiful work of art, shipped from overseas with free postage.”

When Munn attempted to alert users that the ads were fake by leaving comments on their posts, Facebook suspended her account, saying she had been spamming people, thus triggering the site’s anti-fraud algorithm. “I was put in Facebook jail for quite a few days,” she says.

Facebook had previously refused the artists permission to advertise the sculpture on their site, since the figure depicted is nude, and violated the site’s community standards. “But clearly if people stuff enough money in Facebook's pocket, then they're quite happy to,” Munn says.

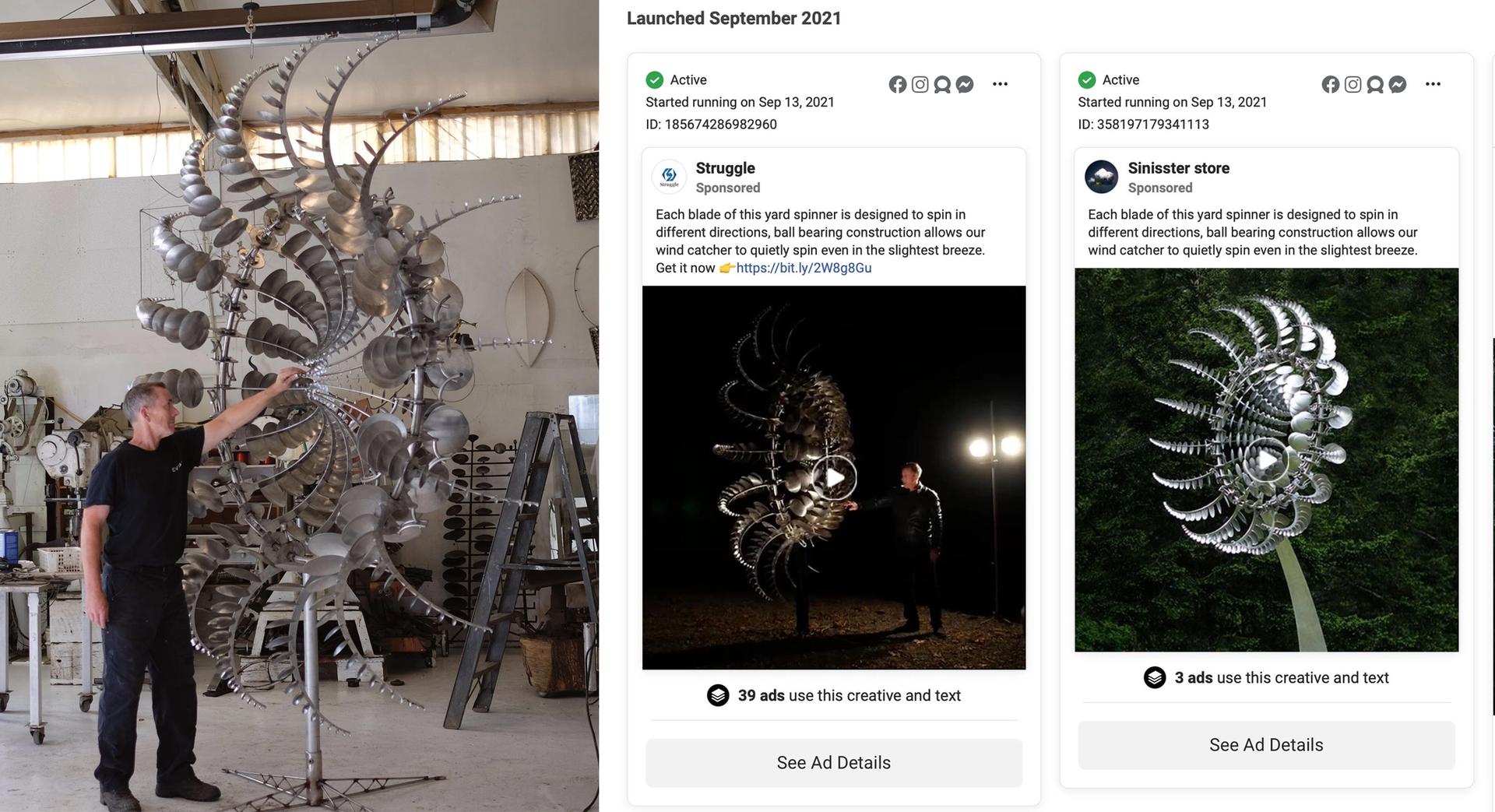

The artist Anthony Howe, who creates kinetic sculptures from his studio on Orcas Island, Washington, likens the scams to a virus. “I don't know how to stop it. It's bizarre,” he says. “When it will end or quiet down I have no idea, but Facebook has definitely got to do something.”

While Howe's large-scale Octo sculptures normally sell for $150,000, he has seen fake ads offering them for as little as $12. And buyers either get nothing, or hand-held spinners that slightly resemble his works.

Anthony Howe, right, with his large-scale kinetic sculpture Octo (2014). Fake ads purporting to sell his work at a steep discount started appearing on Facebook this year, using images and videos from his website. Courtesy of Anthony Howe.

Howe says he has tried alerting Facebook to the situation. "But they just pass the buck,” he says. And while he has considered getting his lawyer involved, as he has in the past when other artists have copied his work, the scale of the fakes generated on Facebook is overwhelming. “I'm just at a point where it's happened so much, it causes so much stress and it's such a drain on the wallet, that we just decided we weren't going to do it anymore,” Howe says.

Other independent artists who have reported images of their work stolen and used in fake ads on Facebook and elsewhere include Marsha Blaker and Paul DeSomma, Cindy Chinn, Mike Locascio, Kevin Merck, Scott Radke, Sadie Revenant, Jack Storms, Will Sutton, Tom Taggart, Jason Tennant, and Benjamin Victor.

“None of this would happen if Facebook did what they were supposed to do,” Cook says, saying the site should better police those who infringe visual artists’ copyright, comparable to how they protect the music and film industry using automatic algorithms.

“There would be no opportunity for a jibberish website to sell and advertise hundreds and hundreds of ads using stolen content without the social media platform allowing it and profiting from it," she says. "That's the salt in the wound is that knowing that Facebook is getting rich doing it.”

This June, in fact, Facebook reported its most profitable quarter ever, with advertising revenue rising 56% to $28.6 billion, compared to the same period in 2020. An estimated 3.5 billion people use Facebook’s apps every month—including Instagram, WhatsApp and Messenger—with more than 90% of them based in countries outside of the US.

And fraudulent advertising is not even a new concern. Last year, Buzzfeed News published a damning report based on interviews with former and current employees who said that Facebook cared more about advertising revenue than the safety and security of its users, allowing scammers, hackers, and disinformation peddlers to run rampant.

There was even a class action lawsuit filed this August in California, brought by dozens of Facebook users who have been duped by similar fake ads offering discounted products, from toys to mechanical equipment.

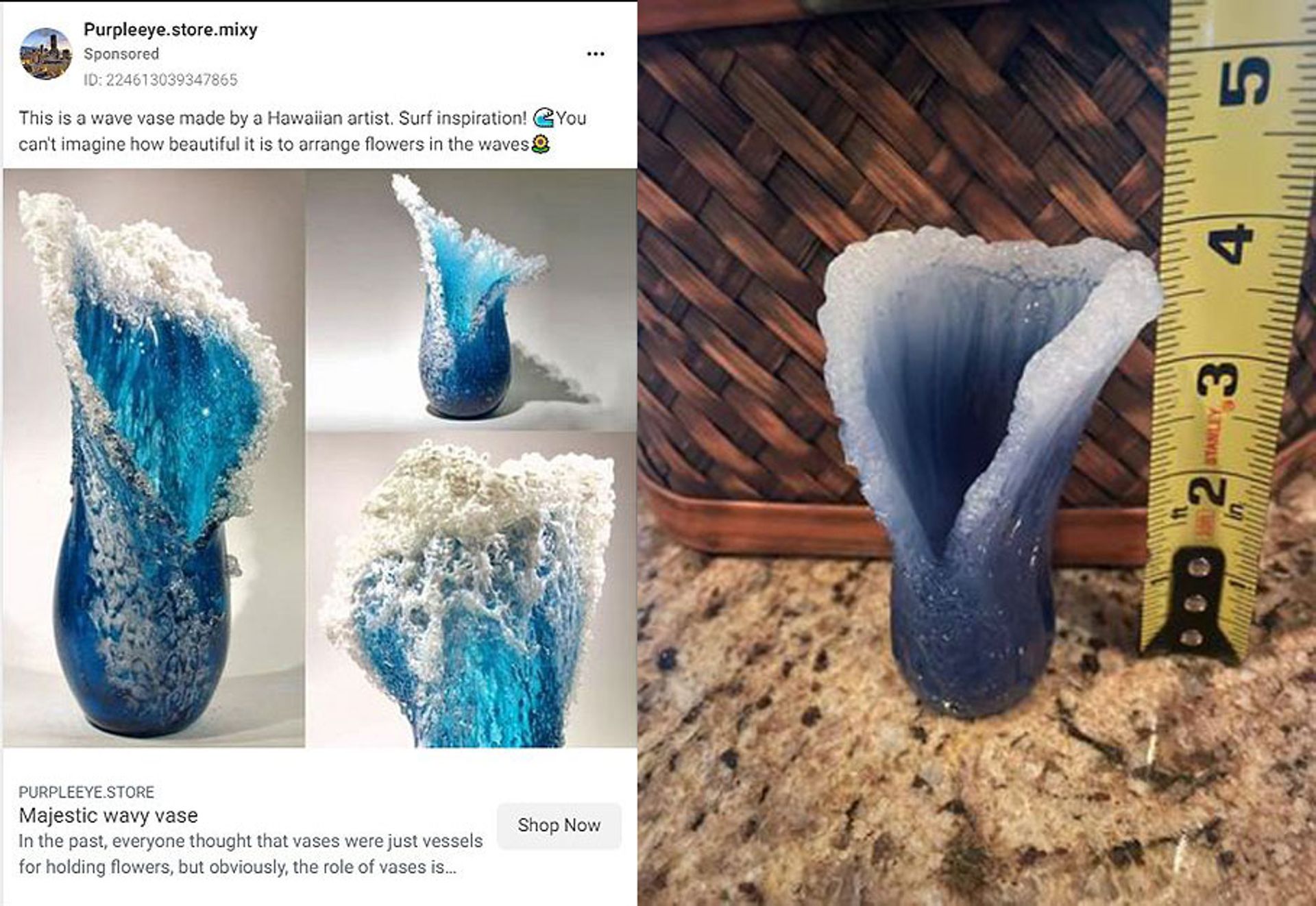

Buyers clicking on a fake ad showing images of a breaking wave glass vase by Marsha Blaker and Paul DeSomma received a cheap knockoff instead.

The social media giant has recently started coming under the crosshairs of regulators, with Congress last month hearing the testimony of whistleblower Frances Haugen, a former product manager at Facebook, who said: "The company’s leadership knows how to make Facebook and Instagram safer but won’t make the necessary changes because they have put their astronomical profits before people.”

Facebook’s press department did not respond to our requests for comment, but according to a statement issued to media the day of the Congressional hearing, the company says it has “invested $13 billion in the safety and security of our platform and have 40,000 people who review content in 50 different languages working in 20 locations all across the world to support our community”.

The community of artists on the social media site, however, feel they have been left to fend for themselves.

Masters at one point considered retraining as a paramedic and giving up the arts entirely. “It's so damaging to your soul, as an artist,” he says. “I mean, nine years it took us to prototype the original and so much love and sacrifice went into making it, developing it. And seeing it be used to rip people off and people's angry and hurt reactions online, it's like seeing somebody you love being violated over and over.”

Cook, who worked as a commercial sculptor for more than 20 years in the toy and gift ware industry, worries the scams will only get worse if Facebook does not take some responsibility. “My career was bound by copyright and licensing,” she says. “This was the first work that had my name attached to it and did not have 'Made in China' stamped on the back. This was the first work that I could claim as my own. And now it's 'Made in China'. I'm fighting tooth and nail to keep my moral rights of authorship to be known as the creator of this work. And I'm losing.”