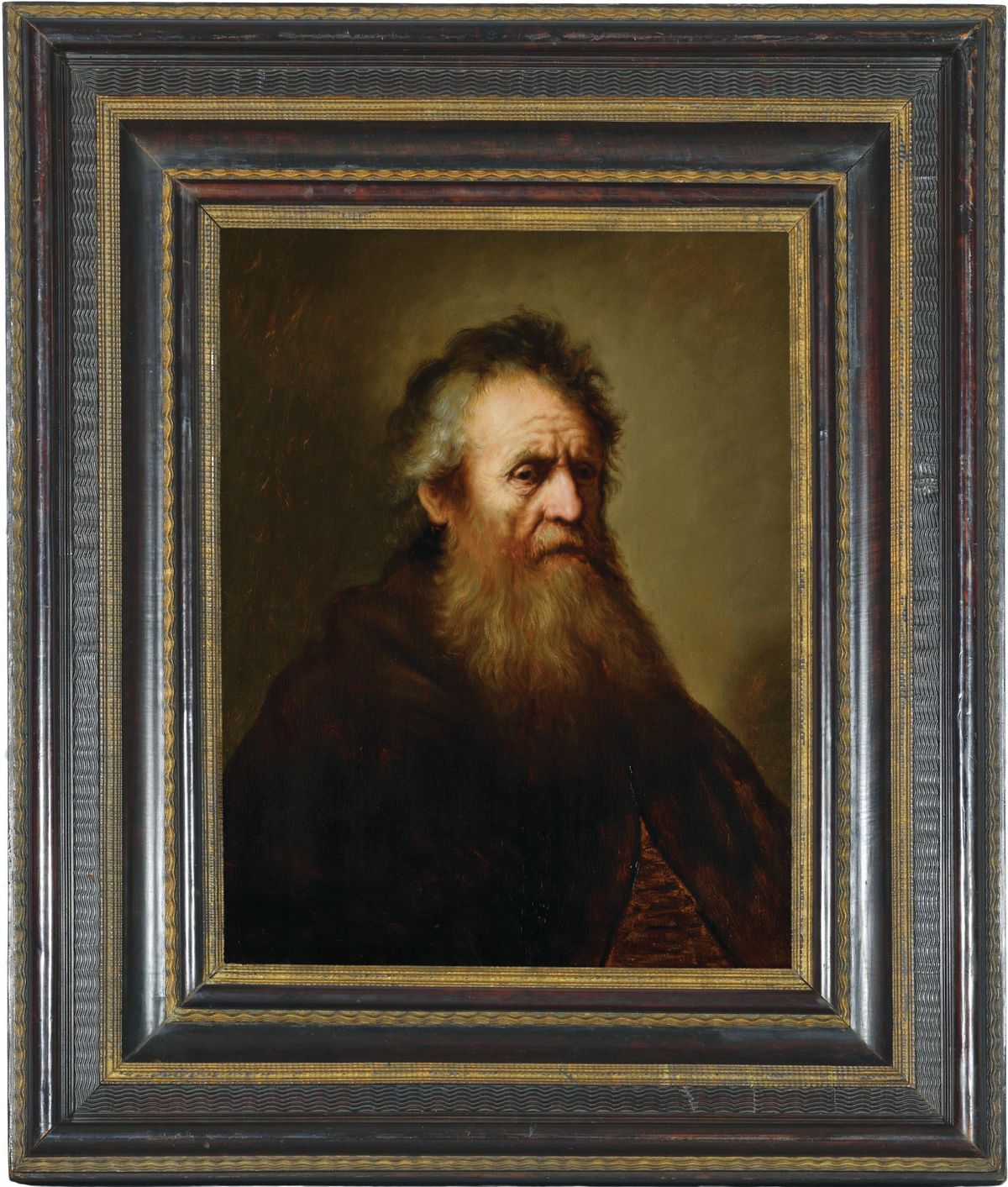

A Dutch painting that was stolen in the biggest art heist in communist East Germany and recovered last year may be the work of Rembrandt, according to research and analysis by curators at Schloss Friedenstein in Gotha.

The painting of a bearded elderly man, dating from between 1629 and 1632, was one of five Old Master works returned to Schloss Friedenstein last year, more than four decades after they disappeared in the theft of December 1979. All five paintings have now been restored and are on display at an exhibition at Schloss Friedenstein called Back in Gotha! The Lost Masterpieces, which runs until 21 August 2022.

The portrait of the old man, which was the most damaged of the five in the theft and sustained deep scratches, has over the years been attributed to Jan Lievens and to Ferdinand Bol, a pupil of Rembrandt. But Timo Trümper, the curator of the exhibition, says analysis of the painting style has ruled out either artist as the author of the work. The attribution to Bol stems from the artist’s signature on the back, but Trümper says that may indicate that he owned the portrait, not that he painted it. He says Bol may have obtained the work after Rembrandt’s bankruptcy in 1656.

The painting is very similar to a work at the Harvard Art Museums in the US. That work bears Rembrandt’s signature, although its attribution has also been a matter of debate. Trümper says that under-painting on the Gotha work indicates that it may have been the original, and that the Harvard painting is a later studio copy.

“It’s a question of interpretation,” he says of the Gotha work. “We can be sure it originated in Rembrandt’s studio—the question is how much of it is Rembrandt and how much his pupils? We have already talked to a lot of colleagues. Half say: ‘No, it’s not Rembrandt, it’s one of his pupils.’ The other half say it’s an interesting theory and they can’t rule it out.”

Disillusioned train driver

The painting has, until now, escaped the attention of Rembrandt scholarship, in part because it was missing for more than 40 years. It was recovered last year, along with four other works: a Hans Holbein the Elder 1510 portrait of St. Catherine; a 1535 Frans Hals portrait of an unknown smiling, moustachioed gentleman wearing a large black hat and white collar; a country road with farmers’ wagons and cows from the studio of Jan Brueghel the Elder; and a copy of an Anthony van Dyck self-portrait with a sunflower by one of the artist’s contemporaries.

The thief, according to an essay in the exhibition catalogue by the Spiegel journalist Konstantin von Hammerstein, is now believed to be Rudi Bernhardt, a disillusioned East German train driver who smuggled the pictures to West Germany, with the help of West German accomplices—a couple who have since died and left the paintings to their children. Bernhardt died in 2016, taking his secret to the grave.

For Schloss Friedenstein, the largest Baroque castle in Germany with a collection built by the dukes of Saxe-Gotha, theft was nothing new. All five of the stolen paintings had been looted once before, at the end of the Second World War, and ended up in the Soviet Union along with many other treasures. The palace has registered around 1,700 items still missing on the German lost art database: Trümper says this does not include thousands of books and coins that were also lost.

The exhibition examines the fate of objects stolen from the 19th century to the present day, including around 80 works that have been returned in the past decades, Trümper says.