This beautifully produced book offers a splendid survey of a staple of British art around 1900. The pictures created by professional artist-tourists are to be found en masse throughout the old municipal art museums of Britain, in auctions and the more traditional dealers’ galleries. Paintings of Mediterranean beaches, the pyramids, Islamic architecture, Venice and Capri—these were standard middle-class interior decorations well into the 20th century. “The pictures of Egypt are bright on the wall” of the blandly comfortable Surrey house described in John Betjeman’s 1941 poem A Subaltern’s Love Song.

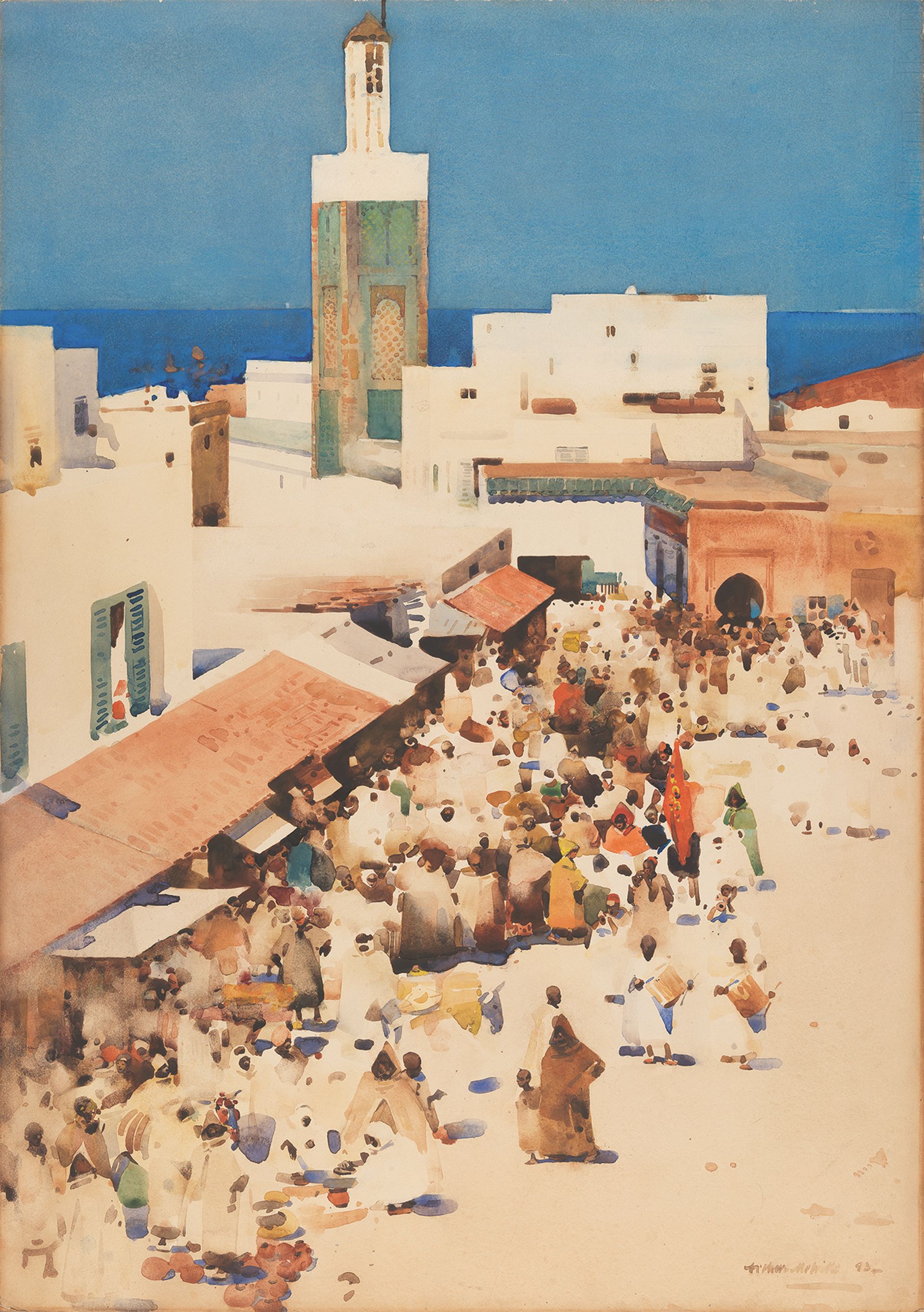

Kenneth McConkey, a leading and longstanding authority on this period, has little to say about the use to which these paintings were put after their execution. He keeps his attention firmly upon the geographies and biographies of the artists themselves, who include such indefatigable stalwarts as John Singer Sargent, John Lavery, Mortimer Menpes and Arthur Melville, but also a host of less well-remembered figures. Featured among the latter are the Scottish Hispanophile Mary Cameron, one of the few women to appear in the book, and Walter Charles Horsley, a specialist in flatly executed but unusual subjects describing the British presence in Egypt. Almost all of the vast number of illustrations have been printed at very high quality, so that even when the text dips into an occasional litany of who went where when, there is never a visually dull moment.

The period covered here coincides precisely with the high watermark of British imperialism

The period covered here of course coincides precisely with the high watermark of British imperialism, and McConkey acknowledges that the tourists’ progress was buoyed by a well-upholstered sense of superiority. Nevertheless our artists’ itineraries were dictated far more by convenience than by a duty to describe colonial possessions. This is essentially a Mediterranean tour (minus Greece, but including North Africa from Tangier eastwards plus Paris and Brittany), a world accessible from London via rail and sea in under a week.

Even McConkey, with his encyclopaedic knowledge of this field, struggles to find examples of picturesque genre or landscape for his chapter on India, despite the subcontinent’s grip on Britain’s imperial imagination. Photographers and newspaper illustrators may have supplied an Indian iconography for the British public, while designers and architects were ready not only to travel beyond Europe but also to learn from what they saw. But painters, unless sponsored by one of the more entrepreneurial London galleries such as the Fine Art Society, needed to fit their tours into a busy working year centred on the exhibition season and its opportunities for sales.

Scottish artist Arthur Melville’s watercolour Tangier (1893) Private collection, courtesy Patrick Bourne & Co., London

McConkey’s final chapter, “On Not Going or Not Coming Back”, stands as an excellent essay on the predicament of the artist-traveller. I would even suggest reading it first before the rest of the book. Oscar Wilde scoffed at trying to capture Japanese beauty by—the absurdity!—actually going there, when that beauty only existed as an idea. All these countless images of humans absorbed into intimate landscapes generated a bland afterimage of numbingly interchangeable hotel art. For the generation of landscape artists who followed those described in Towards the Sun, drawn into the Neo-Romantic mood exemplified by Graham Sutherland, emotional energy was to be sought through depth of vision rather than bodily displacement.

• Kenneth McConkey, Towards the Sun: The Artist-Traveller at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, Paul Holberton Publishing, 260pp, 250 colour illus., £65 (hb), 16 September 2021

• Nicholas Tromans is an independent art historian based in London. His book, The Private Lives of Pictures: Art at Home in Britain, is forthcoming from Reaktion