“It’s to some extent scary and on the other hand it’s very inspiring,” says Stein Olav Henrichsen, the director of the towering new museum dedicated to Edvard Munch by the Oslo fjord. Rebranded simply as MUNCH, it will open on 22 October following a decade of development drama, political U-turns and staggering logistical challenges. The result is one of the largest single-artist museums in the world.

Costing a reported NKr2.25bn ($260m), the environmentally considered design by the Spanish architectural firm Estudio Herreros is as dramatic a reaction to Oslo’s shoreline as Munch’s The Scream was in the late 19th century. With 11 exhibition halls spread across 13 floors and capped by a panoramic restaurant, it provides a colossal stage for Munch’s extraordinary gift to the city on his death in 1944: around 28,000 works—paintings, drawings, sculptures, prints and photographs—along with his papers and personal effects.

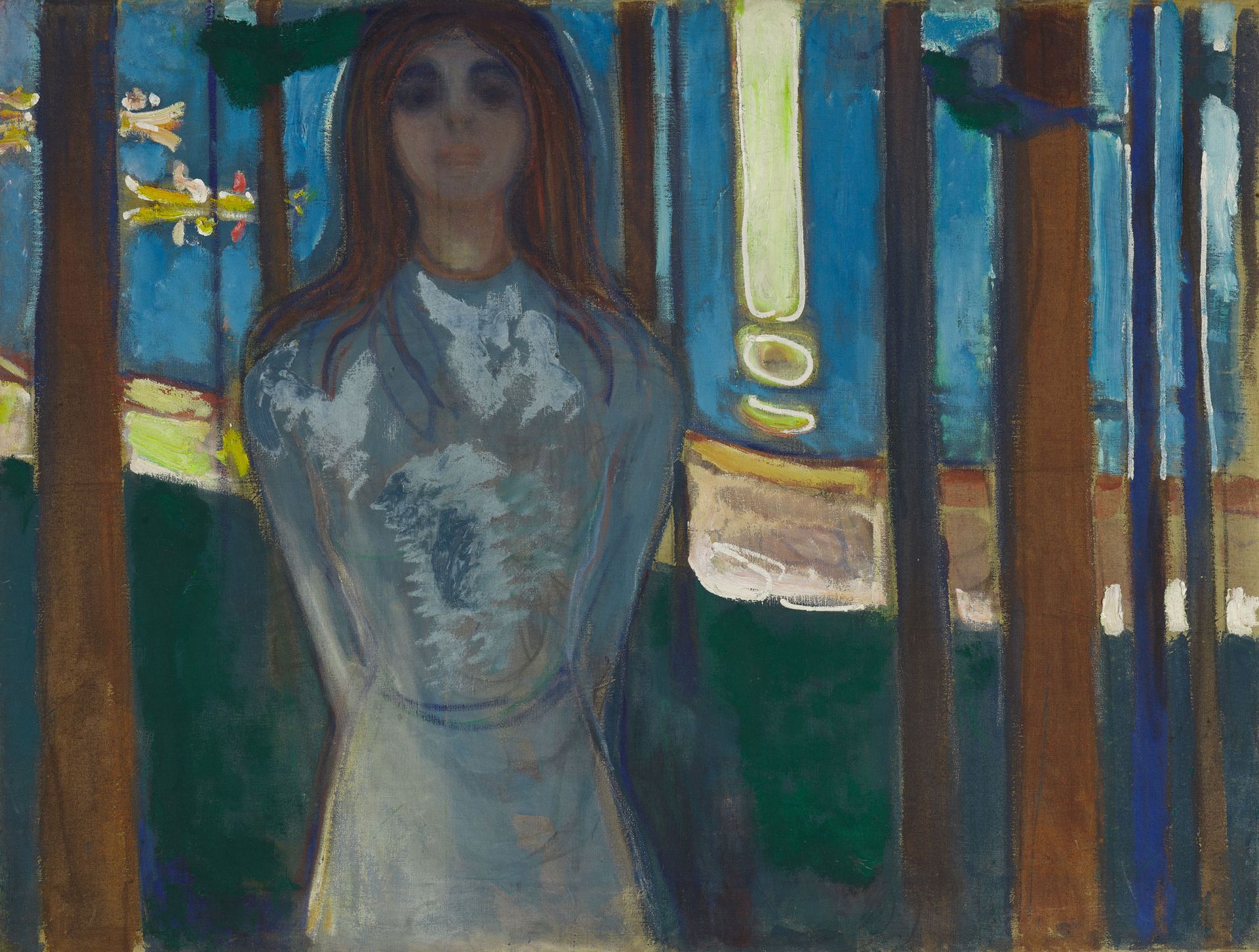

Summer Night / The Voice (1896) by Edvard Munch Munchmuseet

Since 1963, the collection has been housed in a low-lying, utilitarian building in the residential district of Toyen. The decision to move was prompted by the 2004 theft of two prized paintings, The Scream (1910) and Madonna (1894). The works were later recovered but “after the robbery there was a sense of emergency in terms of there being a new museum”, Henrichsen says. While security was the primary concern, the conditions in which Munch’s works were being presented were also “not on the level that this collection deserves”. The new museum, situated next to Oslo’s iconic opera house in the bay of Bjorvika, will provide five times more visitor space.

The city of Oslo approved the new museum in 2008, launching an international design competition, but the process was fraught with complications. “Only two years later [the contest] was terminated and then two years later again it was re-established,” Henrichsen says. Political wrangling over the cost, the proposed waterside location and what would happen to the Toyen site continued until a majority vote was eventually reached in the Norwegian parliament. Today, Toyen is being redeveloped with park and leisure facilities while the new museum will open with a weekend of events hosted by King Harald and Queen Sonja of Norway.

The 13-floor building by the Oslo fjord during construction © Høyden AS - Thomas Horgen

The most daunting part of the move, according to Henrichsen, was relocating Munch’s largest work, The Researchers (1911-25), which measures around 50 sq. m. “It had to be moved from Toyen through the roof, on lorries through the city and then on a small ship from one part of the fjord to the museum. Then we winched it up to a small hole in the sixth floor. We had people hanging down from the roof to guide it. If we’d had wind they could have been crushed.”

The ambitious project also triggered a much-needed inventory of the museum’s collection. “For the first time in history we have been able to go through everything,” Henrichsen says, “and when it comes to the art, digitise almost everything”.

Personal objects, from furniture to artistic materials to cigarette butts, will create an immersive virtual representation of the artist’s home

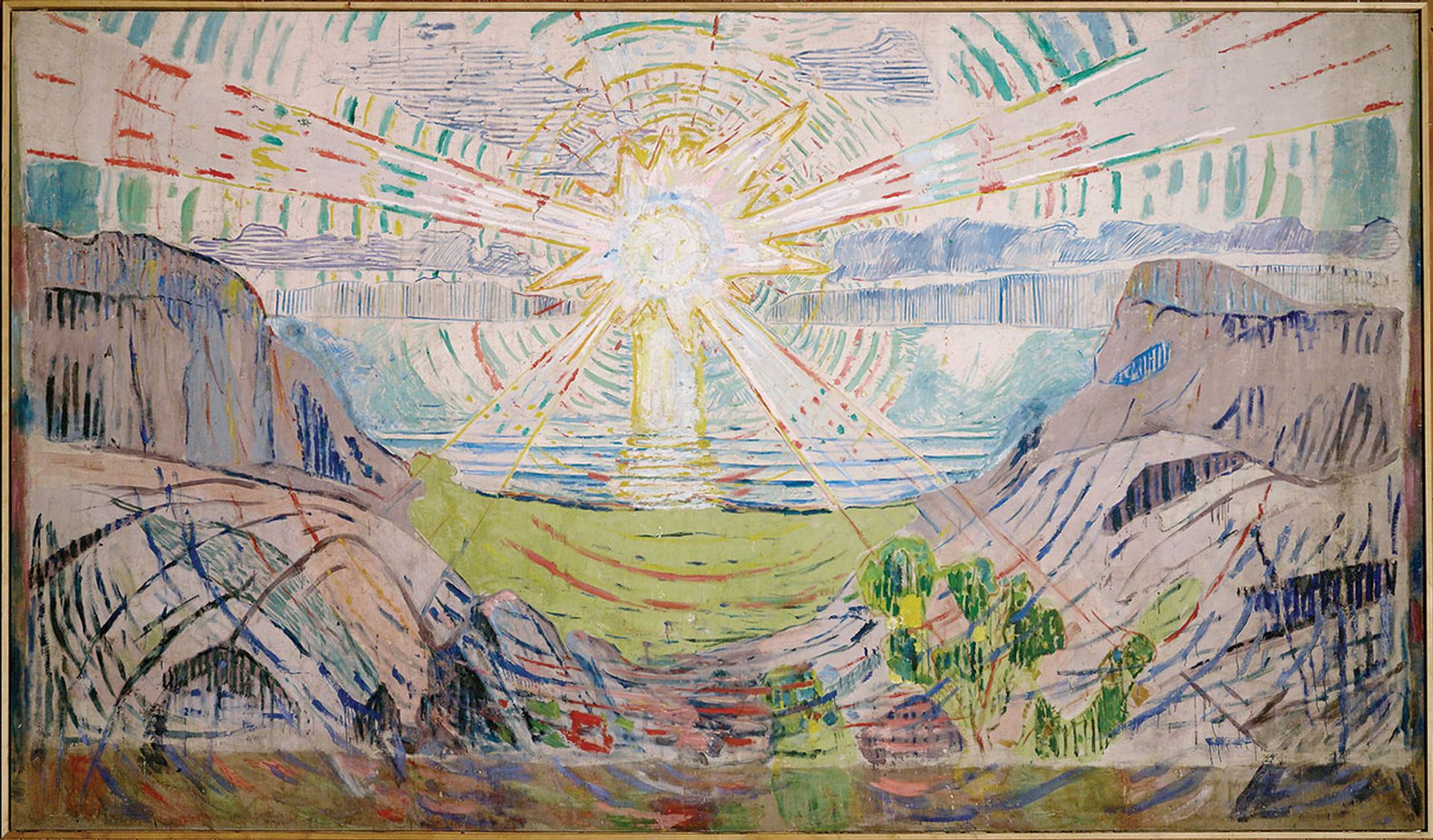

Munch’s bequest represents “his whole life”, says Jon-Ove Steihaug, the museum’s head of exhibitions and collections. Curatorially, MUNCH separates the man from the work. His art is organised thematically rather than chronologically, with permanent exhibitions including Infinite, a survey of Munch’s main themes and motifs, and Monumental, which provides room to view the huge canvases of The Researchers and The Sun (1910-11).

The Sun (1910-11) is one of two monumental canvases that Munch originally created for Oslo University Courtesy of Munch Museum

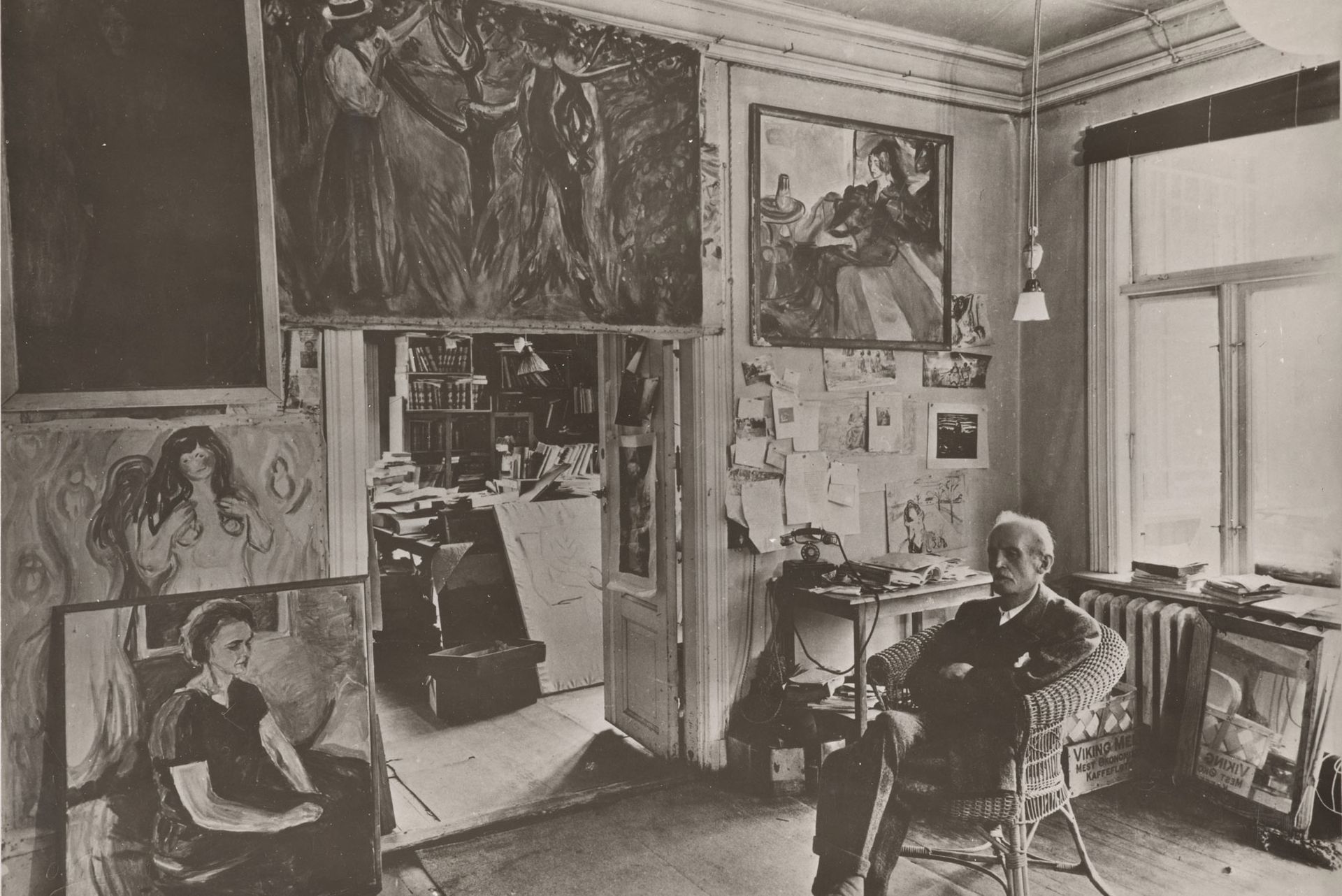

Meanwhile, Shadows investigates the artist’s life and specifically his later years at Ekely, his estate outside Oslo. Digital exhibits and personal objects displayed for the first time, from furniture to artistic materials to cigarette butts, will create an immersive virtual representation of the artist’s home, which was demolished in 1960. The ephemera reveals “something different about Munch as a person”, Steihaug says. They also reference his compositions, from the chair in which he depicted his dying sister in the 1880s to the geometric bed cloth seen in his late self-portrait Between the Clock and the Bed (1940-43).

Edvard Munch in his living room at Ekely in 1943 Photo: Ragnvald Væring

The scale of the Bjorvika building will allow the collection to be remixed within various, perhaps unexpected, contexts. The Loneliness of the Soul, an exhibition placing Munch in dialogue with Tracey Emin, first shown at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, will fill two floors of MUNCH’s opening season. Emin’s 9m-high bronze sculpture The Mother will be permanently installed outside the museum next spring, when the museum will also rock out in a collaboration with the Norwegian death metal band Satyricon. Steinhaug says the curatorial strategy is “not for eternity” but likely to change “organically” over time.

MUNCH is billed as more than a museum: it aims to become a social hub for diners, shoppers, gig-goers and swimmers (the location proved a magnet for sun-seekers this summer) as much as a place to see art. “Forget everything you know about museums—this is something different,” Henrichsen says.

The new museum will also have the capacity to host touring blockbuster shows. And while Henrichsen will not be drawn on any dream exhibition projects in the pipeline, he observes that there are echoes between Munch’s oeuvre and the works of contemporary art heavyweights Jasper Johns and Anselm Kiefer. Watch this (vast) space.