An invisible disease that is spreading throughout the world has become an obsession for the Berlin- and London-based artist Sung Tieu, the winner of this year’s Frieze Artist Award in London. No, it is not Covid-19. The strange sickness called Havana Syndrome has been baffling doctors, scientists and intelligence officers since it first appeared in the Cuban capital in 2016. The victims have all been US officials and intelligence staff, and much of the information about the illness has been kept secret.

The first cases emerged when CIA agents staying at a Havana hotel reported hearing a piercing noise or a feeling of pressure in their heads followed by severe symptoms of nausea and vertigo and, later, persistent memory loss, dizziness and fatigue. Today, “attacks” on more than 200 US victims have been reported in countries from China and Vietnam to Germany and Serbia, and still no one knows the cause. (Theories include microwave devices and crickets native to Cuba.)

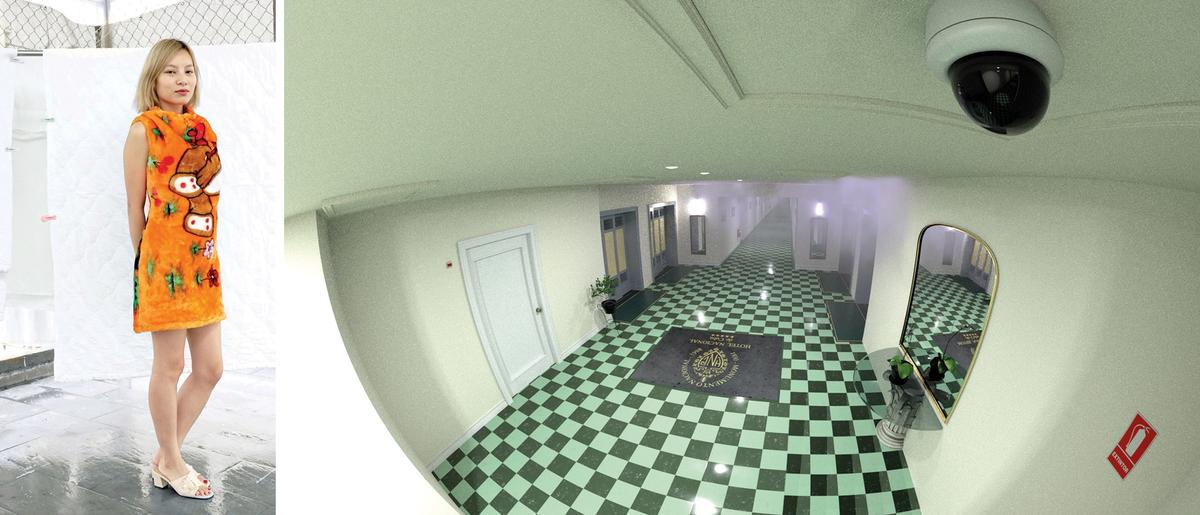

For her Frieze Artist Award commission, Tieu is building on her 2020 Nottingham Contemporary exhibition about the syndrome, In Cold Print, in which she exposed herself to a reconstruction of the acoustic attack. Her new video, Moving Target Shadow Detection (2021), reconstructs the interior of the Hotel Nacional de Cuba where the first known cases occurred. Here, she tells us about her research and how she is making secret sound weapons visible.

The Art Newspaper: How did you become interested in the topic of warfare?

Sung Tieu: I think that it is something that is maybe not straightforwardly visible as “war”. My research started with Ghost Tape #10, which was a sonic weapon developed in the 1960s by the US Army’s Psyops [psychological operations] to be used in the war in Vietnam. [It was designed to intimidate and demoralise Vietnamese soldiers.] Through that research, I encountered the Havana Syndrome in around 2018 and I just kept it in the back of my mind as something weird but really interesting. Then, when I was working on the exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary, it resurfaced. I was thinking about the psychological impact of sound, especially when our world is so saturated with images. I feel like sound has become much more impactful because of this visual overload; it is so hard for an image to penetrate us, whereas I think that sound can do it in more subtle and more subconscious ways.

Sung Tieu's exhibition In Cold Print at Nottingham Contemporary, (8 February-31 August 2020) © Sung Tieu. Courtesy of the artist, Emalin, London and Sfeir-Semler, Hamburg & Beirut. Photo: Lewis Ronald (Plastiques)

How do you go about researching a disease as mysterious as Havana Syndrome?

I spoke to many scientists and journalists such as Jon Lee Anderson, who co-wrote the first big feature on the Havana Syndrome, for the New Yorker. He has interviewed US officials and has great insights, but he doesn’t have a conclusive answer. That was also key for me working on it—I didn’t have all the information and artistically I think that is interesting. If I knew exactly how the Havana Syndrome was made up, maybe there wouldn’t be a need to creatively, sonically and visually investigate it.

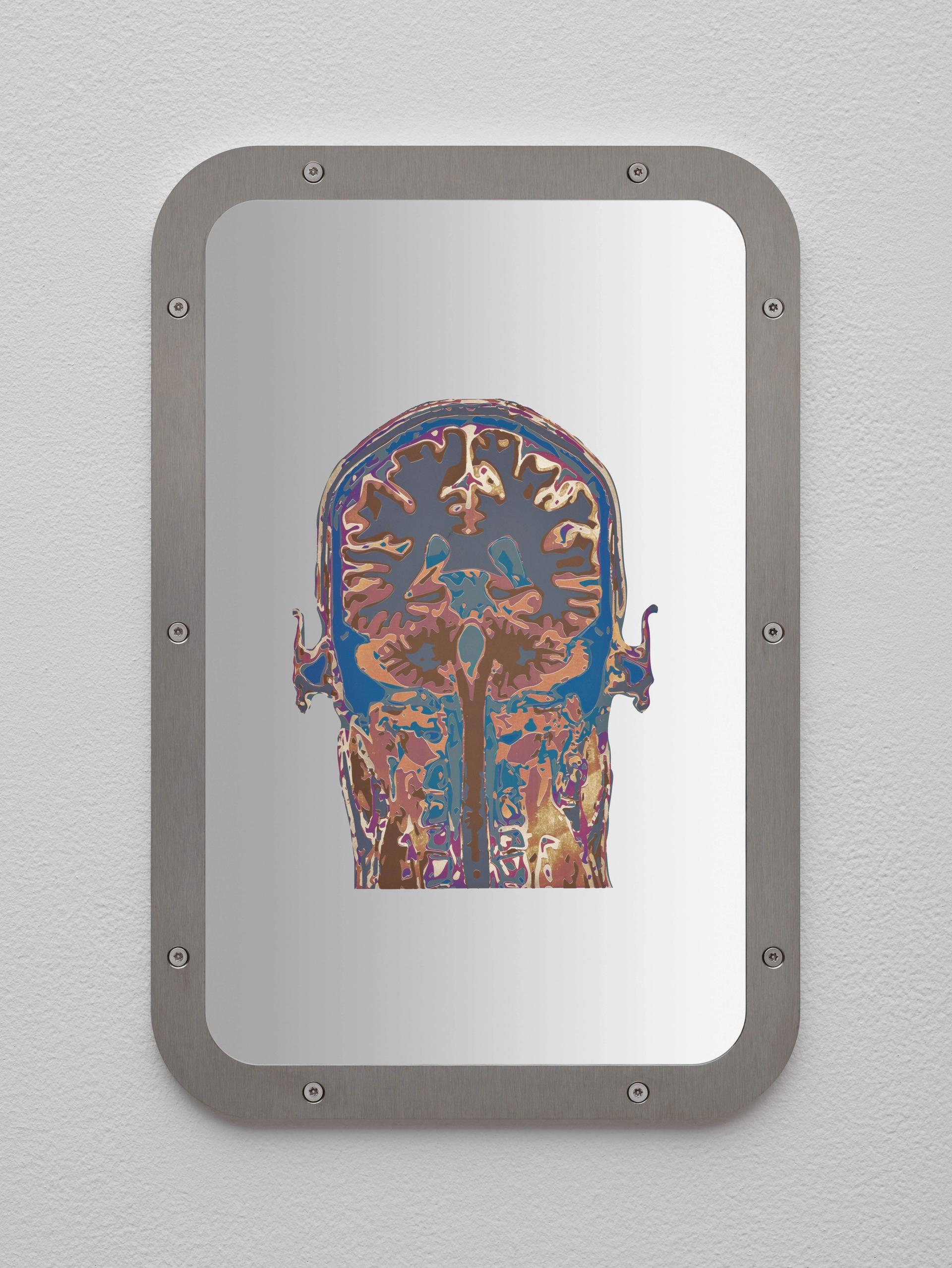

Sung Tieu 's Exposure to Havana Syndrome, Brain Anatomy, Coronal Plane, (Sample 9) (2021) © Sung Tieu . Courtesy of the artist, Emalin, London and Sfeir-Semler, Hamburg/Beirut. Photo: Hans-Georg Gaul

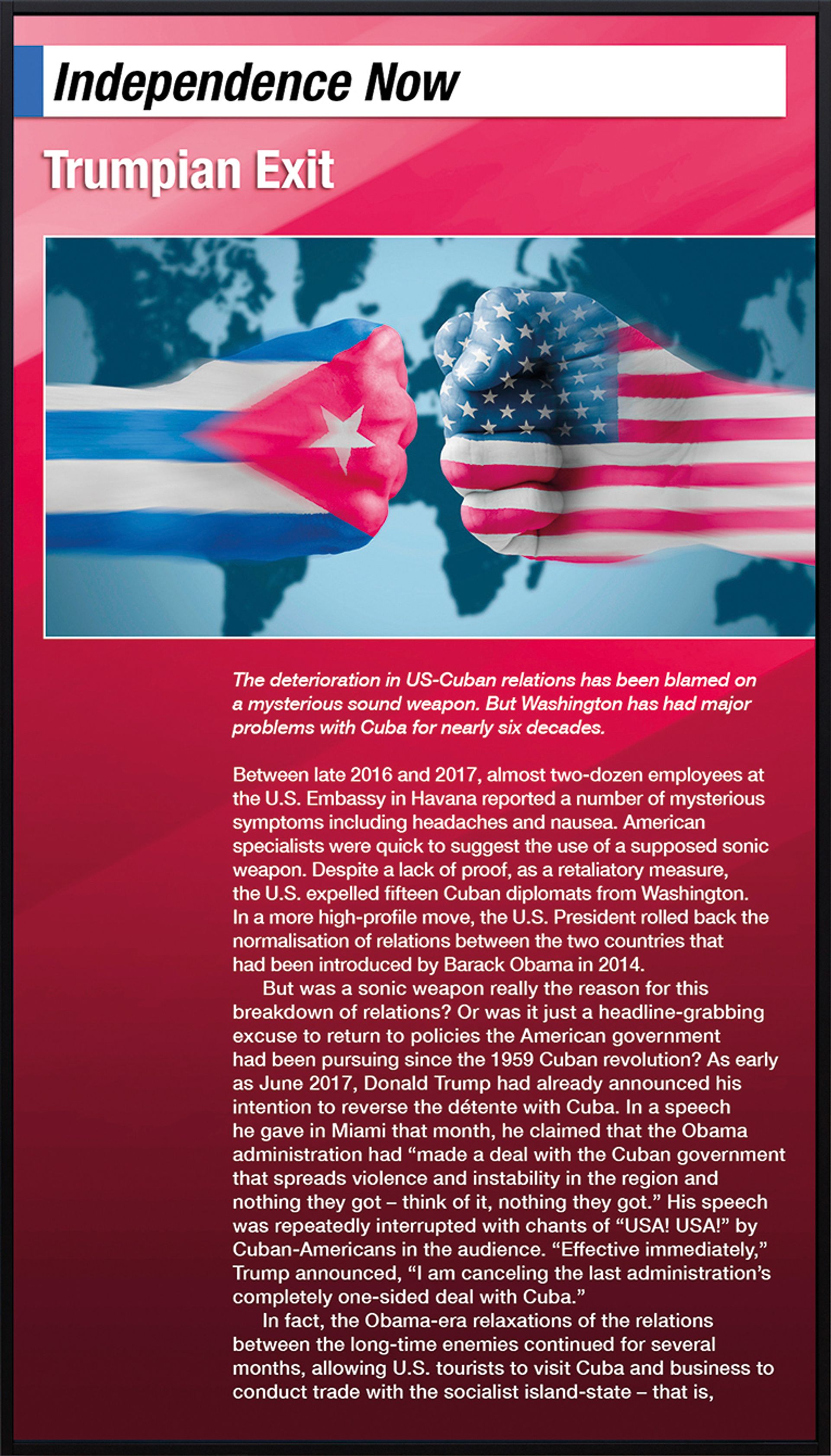

I’m also interested in how the illness is portrayed in reportage because you can’t remove it from certain global political agendas. The cause and effect are difficult to track, but it has certainly affected political affairs. Many argue that the whole intention is to disrupt political affairs. I’m fascinated by how the story is told: how it is being pictured, how the viewpoints are being laid out, and which political arguments are being used to justify certain sanctions or political decisions.

How did you present your research in the Nottingham Contemporary exhibition?

The show was split into two iterations, with the first one changing unannounced. A few weeks in, I changed the configuration of the steel fences I was using as walls, and changed the information on screens, while the sound work remained the same. The first half lasted for around six weeks and showed scans of my brain’s reaction to listening to a reconstruction of the sound weapon, a multi-channel sound installation, and articles that I had written based on my research. These articles were quite affirmative towards the Havana Syndrome and the American perspective. Then, in the second iteration, I tried to show more critical views—that perhaps the Havana Syndrome can’t exist in the way it is described. There are scientists who claim there is no frequency in this world that you can’t hear that can cause severe brain concussions.

One of the articles that Sung Tieu has written based on her research on the Havana Syndrome, Trumpian Exit (2020 ) © Sung Tieu . Courtesy of the artist and Emalin, London. Photo: Lewis Ronald (Plastiques)

Who and what do you think is causing the syndrome?

There are multiple theories, but I wouldn’t claim to have the answer. Many US officials suggest it might come from Russian intelligence, since there are political motivations for developing such a weapon. Russia also has a history of experimenting with microwave weapons. But I am not really interested in what is true or false. I am more concerned with how sounds penetrate our bodies and brains, and activate our psychic imaginary.

Are you ever worried about your own safety while investigating this?

Yes, I am in a way. When you dive into a topic that is so current and has such strong political impact and has caused real illnesses, you have to be aware of the material you are dealing with. I wanted to shoot the film in the specific hotel room in Cuba where the first attacks supposedly occurred. Of course, I had to consider the risks that such an operation would involve for me and my team.

Did you go to Cuba?

No, we didn’t receive the filming permission from the Cuban culture ministry, for several reasons, one being the pandemic. That only adds to the mystery. So I worked with a team to create 3D renderings of the hotel in Havana.

A still from Sung Tieu's video Moving Target Shadow Detection (2021) Courtesy of the artist

How does the video play out?

The video follows a mosquito-type animal flying through the hotel corridor, slowly leading us into the hotel room where supposedly a CIA member was attacked by these mysterious frequencies. Through this perspective, and the switch between cameras, from CCTV camera views to ones resembling drone footage, I’m trying to draw out links between various sites of war and show how this hotel has also become a site of war. The fuzzy footage that we are so familiar with from war zones in Iraq and Afghanistan that is often taken by military equipment is now capturing the CIA’s own hotel rooms. In a way, the weapons that the US military or Psyops have produced in the past are haunting them in the present. You can’t go out into the world and produce all these military tools without it psychologically affecting yourself as well. So I’m interested in how the Havana Syndrome is causing harm in the sense that it is like a collective subconscious trauma—of having that knowledge that you have used sonic weapons against other nations and people, and now they are being used against you.

• Moving Target Shadow Detection premieres at No. 9 Cork Street on 20 October, followed by a conversation with Sung Tieu, and will then be available to stream online at frieze.com. The Frieze Artist Award is presented in partnership with Forma