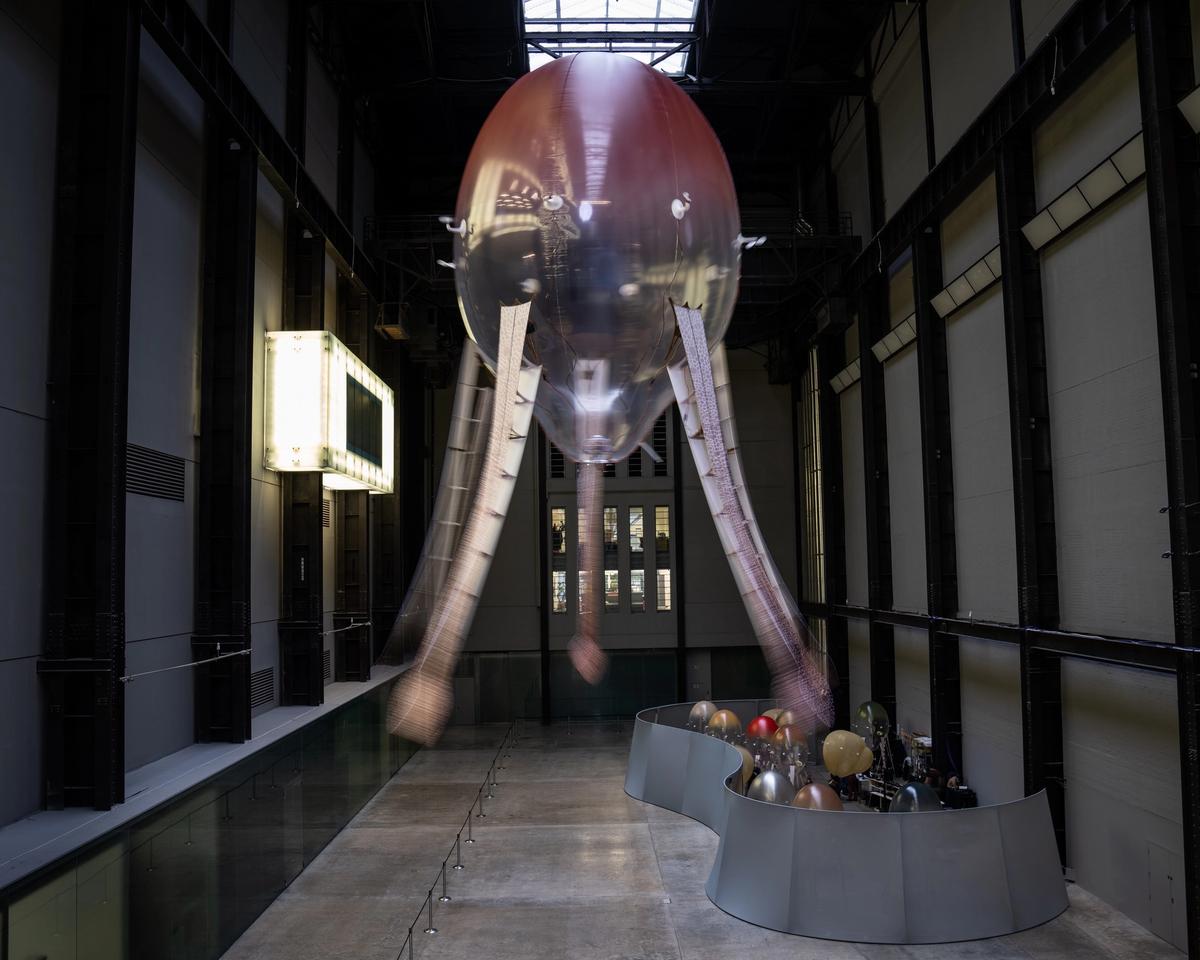

Two species of intelligent robots have moved into some prime, Thames-side real estate: Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. Collectively named aerobes, the floating orbs that the New York-based artist Anicka Yi has created to inhabit the cavernous space are called planulae (the hairy, bulbous ones) and xenojellies (the ones with patterned tentacles). Inspired by ocean life forms and mushrooms, the helium-filled shapes move around using rotors and a small battery pack. Together, they create an “ecosystem” within the museum, Yi says, interacting with their environment and visitors, and displaying individual and group behaviours.

Behind the scenes, an incredible amount of technology and research is powering this floating family. A team of specialists has developed the aerial vehicles using software that gives each a unique flight path. The software, called an artificial life programme, generates a huge range of journey options for the orbs to take and therefore simulates the somewhat unpredictable processes of natural life. This kind of technology is normally used in scientific studies but has also been employed to create lifelike visual effects and animations.

Installation view of the Hyundai Commission: Anicka Yi: In Love With The World at Tate Modern, London. Photo: Will Burrard-Lucas

The robots will respond to the space and people around them by receiving information from electronic sensors positioned around the venue. The signals affect them individually and as a group so that they will behave differently upon each encounter. “Like a bee’s dance or an ant’s scent trail, the aerobes communicate with each other in ways we cannot understand,” a Tate Modern statement says.

As well as returning machines—admittedly of an altogether different kind—to the empty belly of the Turbine Hall, the heart of the former Bankside Power Station, Yi is also using her aerobes to question ideas around intelligence and our focus on the brain as its main transmitter. “Most AI functions like a mind without a body, but living organisms learn so much about the world through the senses,” she says. “Knowledge emerging from being a body in the world, engaging with other creatures and environments, is called physical intelligence. What if AI could learn through the senses? Could machines develop their own experiences of the world? Could they become independent from humans? Could they exchange intelligence with plants, animals and micro-organisms?”.

“Yi’s installations are unforgettable, using the latest scientific ideas and experimental materials in unexpected ways”Frances Morris, director of Tate Modern

The other element to Yi’s work is the use of scent: the artist has “sculpted” the air by creating what she describes as “scentscapes”. A combination of smells emitted into the space will change throughout the weeks of the commission, much like the behaviours of the robots in residence. Yi has selected smells inspired by the history of the Bankside area surrounding Tate Modern. These include marine scents from the Precambrian period (the earliest in Earth’s history), odours of vegetation from the Cretaceous period (around 145 million to 66 million years ago), the scents of spices that were used in the hope of counteracting the Black Death in the 14th century, and the smell of coal and ozone from the Industrial Revolution.

The scents are meant to remind visitors of our connection to our environment and to one another. “Yi is interested in the politics of air and how this is affected by changing attitudes, inequalities and ecological awareness,” the museum statement says. “The space is not empty but filled with the air we all share, and on which we depend.”

“Yi’s installations are unforgettable, using the latest scientific ideas and experimental materials in unexpected ways,” says Frances Morris, the director of Tate Modern. “The results not only engage the senses, but also tackle some of the big questions we face today about humanity’s relationship to nature and technology.”

• Hyundai Commission: Anicka Yi: In Love with the World, Tate Modern, London, until 16 January 2022 (free but booked tickets required)