A year ago this month, when it was still closed to the public because of the pandemic, the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA) took a major step toward interrogating a controversial 18th-century group portrait in its collection centering on an early benefactor to the university, Elihu Yale. Responding to pointed criticism of the painting’s subject from students and others, it removed the work from a gallery wall, replacing it with a pointed critique by the African American painter and sculptor Titus Kaphar.

Around the same time, the museum embarked on exhaustive research on the portrait, which is now dated to around 1719 and was presumably painted at Elihu Yale’s house in London. Foremost on the research team’s minds was the identity of an enslaved boy of African descent depicted in the work, who has poured madeira into glasses for the American-born philanthropist and three other privileged white men gathered around a table.

Chillingly, the Black child wears a silver collar and padlock around his neck: while the collar was apparently not used to tether him to shackles, it was clearly intended to deter escape.

The silver collar worn by the enslaved boy in the painting was common for such captives in British society, with similar versions fashioned in steel or brass

The painting is now set to go back on view next week, with additional context yielded by the research. And while the museum has not yet determined who the boy is or where he came from, it is forging ahead in the belief that its investigation is “on much surer ground than before”, says Courtney Martin, the director of the museum.

Kaphar’s riposte, a 2016 painting titled Enough About You, collapsed the four white men into a crumpled blur and transformed the boy into a defiant personality, rid of his collar, who stares out at the viewer from a gold frame. It remained on view at YCBA for six months. The artist has said he wanted to “imagine a life” for the child, with “desires, dreams, family, thoughts, hopes” that the original 18th-century artist—now thought to be a Dutchman active in Britain named John Verelst—was indifferent to. The work harnessed indignation over moral travesties past and present as well as glaring deficiencies in representations of people of colour today.

Titus Kaphar, Enough About You (2016). Courtesy of the artist, Photo: Richard Caspole.

Mindful of Kaphar’s critique and others, Martin, who took over as director of the Yale museum in 2019, commissioned the research into the 18th-century painting, now retitled Elihu Yale with Members of his Family and an Enslaved Child, last fall. “People contacted me and said, ‘Your institution has all these horrible paintings–what are you going to do about it?’”, she recalled in an interview.

At first, the criticism perplexed her, Martin says, “because I didn’t think it was true”.

“And then I realised slowly what they were talking about: that it was that painting,” she says of the group portrait. “It was hard for me to hear because from my vantage as an art historian, it’s a minor painting by a minor artist, and we have major paintings by major artists.” The YCBA owns important examples by William Hogarth, J.M.W. Turner, Thomas Gainsborough, Joshua Reynolds and many others.

Acquired in 1970, the 18th-century painting was the first to formally enter the museum’s collection, which was initially established through an enormous gift to Yale of British works acquired by the philanthropist Paul Mellon. The museum opened in 1977.

Homing in on the depiction of the enslaved child, the YCBA’s research team enlisted a pediatrician to estimate the boy’s likely age, which was determined to be around 10, says Martin. Drawing on records from the early 1700s, the curatorial investigators note that it was then routine to ship boys of African descent under 10 years of age to Britain to serve as domestic servants in affluent households. The child would probably have served as a so-called page in the household of one of the men depicted.

While slavery was not then legal in Britain, thousands of Black children and adults were bought there in “slavish servitude”, the researchers report, attesting to the nation’s investment in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The silver collar worn by the boy was common for such captives in British society, with similar versions fashioned in steel or brass.

Why has so much effort gone into the study of what Martin considers to be a decidedly unimportant painting?

One answer is the poignant situation of the boy, highlighted by a contemporary focus on historical injustice. In the minds of museumgoers, “If we put a painting like that out into the public, we validate it,” says Martin. “The public says, everything you put up, you believe in, 100%.”

“I don’t think that’s true for this painting at all,” the director says, adding, “It’s hard for me as an art historian to give this painting credence.” But as art institutions address imbalances in race and gender in their collections, each is “always in a conversation about itself” and re-evaluating its presentations, Martin notes.

In the course of its studies, largely conducted remotely, the Yale museum’s team has also revised its assumptions about the four men depicted in the foreground of the painting, originally dated to 1708. In addition to Elihu Yale, at the centre, the man in the rear left had been thought to be a lawyer named James Tunstall who was negotiating a contract for the marriage of Yale’s daughter Anne to Lord James Cavendish. Now the figure at rear left is thought to be David Yale, who was chosen as an heir to Elijah Yale because the latter had no sons. Technical analysis indicates that David Yale was added later to the painting, eclipsing a landscape element.

In the left foreground is Lord James Cavendish, whose identity has not been disputed by the researchers. And at right, they propose, is another son-in-law, Dudley North, who married Elihu Yale’s daughter Catherine and lived near his father-in-law in the Bloomsbury district in Camden. Previously, that figure had been thought to be William Cavendish, elder brother of James and the second Duke of Devonshire, but comparisons from other portraits of the period show a compelling resemblance to North.

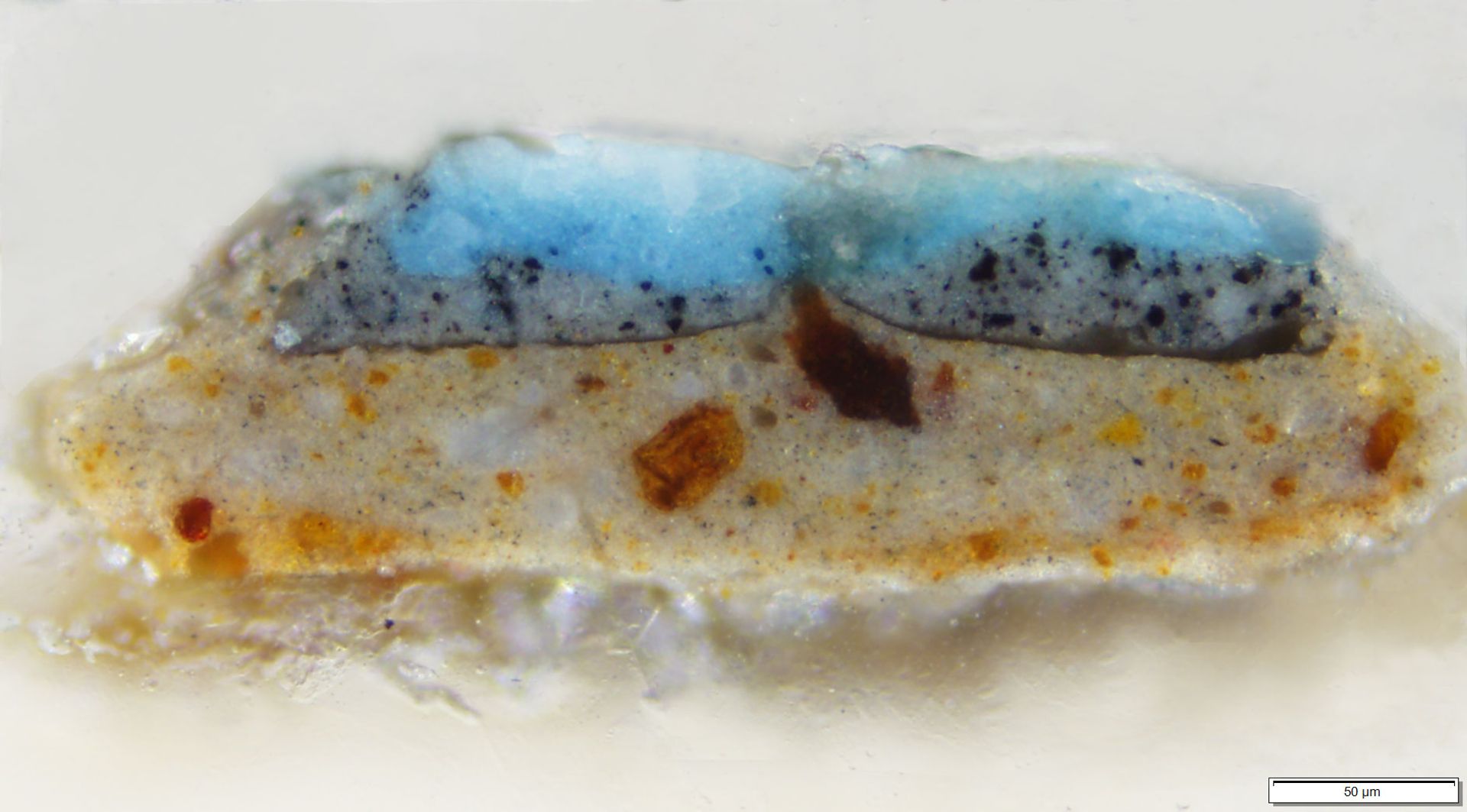

A cross section taken from the painting where analysis has identified the pigment Prussian Blue. Photo: Jessica David

The discovery by YCBA technicians of Prussian blue pigment in North’s blue coat, a substance that was not in use among artists in Britain until 1719, meanwhile shifted the presumed date of the painting from 1708 to between 1719 and 1721.

The researchers have also suggested that a man playing the violin in the background of the painting while Elihu Yale’s grandchildren dance in a circle is Obadiah Shuttleworth, a musical prodigy in London who gave the children music and dancing lessons.

The team sees the work as a family portrait intended to shore up the legacy of Yale, a wealthy merchant and former colonial administrator in India, in his final years in London. His reputation was under assault, Martin notes. ‘’Like a number of other East India Company officials who had enriched themselves” through profiteering in India, “Yale was derided by those in London jealous of his wealth and judgmental about his relatively humble background,” she says. “He was a member of a family of the provincial gentry who had emigrated to America, but returned to Britain with a fortune sufficient to broker marriage settlements for his daughters with aristocratic families.”

The label for the painting has been rewritten to emphasise the servitude of the enslaved boy. Researchers have also identified at least 50 other paintings made in Britain between 1660 and 1760 that portray people of African descent in metal collars, reflecting the nation’s entrenchment in the slave trade. Martin also points to similar examples in the American colonies, reflected in an image of a collared slave in Mining the Museum, Fred Wilson’s revelatory 1992 installation exploring the collection of the Maryland Historical Society.

While the researchers have not determined the identity of the black servant in the YCBA’s painting, they have searched every potentially relevant baptism, marriage and burial record in each parish in Camden, Martin says—“often the only place of record for the young men of African and Indian heritage who had served as attendants in the households of the elite”. Yale and his sons-in-law also owned country houses in Suffolk, Buckinghamshire, and Derbyshire, and research work continues into parish registers there, Martin adds.

The group portrait is not the only depiction of Elihu Yale to stir dissent at the university, which altogether owns seven paintings of its namesake as well as a snuffbox with his portrait on it. Although he is not known to have owned slaves, three of the seven paintings show him with an enslaved attendant: A portrait depicting Elihu Yale with a servant of assumed Indian heritage was removed from its position above the mantel in the university’s ornate Corporation Room in 2007 because of its racial overtones, Martin notes.

After the eight-month loan to YCBA, Kaphar’s critical counterpoint to the original painting was returned in May to its owners, the Los Angeles-based contemporary art collectors Arthur Lewis and Hau Nguyen. In a three-part online symposium convened recently by the museum, the couple discussed the import of the work with the artist. Audiences have been invited to share their thoughts about both paintings.

As the museum gears up to return the 18th-century group portrait to the gallery, Martin is braced for the potential response.

“I don’t think anyone wants to validate any of the more negative aspects of the painting,” she says. “How long will it stay? That’s the answer I don’t have just yet. The conversation is evolving.”